These 2 Bipartisan Proposals Would Hold Presidents Accountable for ‘Improper’ Payments

Rachel Greszler /

Suppose that a typical American family that spends about $73,000 per year was budgeting for next year and realized it spent an increasing amount—$4,600 last year—by sending payments to the wrong people and in the wrong amount.

Sound budgeting would say that family should include “improper payments” in its budget. And assuming it doesn’t like wasting thousands of dollars a year, that family should identify its failures and make changes so it sends payments only to people it owes money—and doesn’t send more than it owes.

A set of bipartisan proposals introduced in Congress seeks to impose accountability on—and ultimately rein in—the federal government’s massive and rising improper payments.

The Improper Payments Transparency Act (HR 8342), introduced by Reps. Rudy Yakym, R-Ind.; Jack Bergman, R-Mich.; Jimmy Panetta, D-Calif.; and Scott Peters, D-Calif., would require the president’s budget request to include information about and explain how agencies are addressing these payments gone wrong.

Just as an addict’s recognition of his problem is the first step to recovery, the federal government’s recognition of improper payments in its budgets is a first step to recovering taxpayers’ dollars.

The second proposal, the Enhancing Improper Payment Accountability Act (HR 8343), was introduced by Reps. Blake Moore, R-Utah, and Abigail Spanberger, D-Va.

This bill includes recommendations from the Government Accountability Office to impose stricter, more timely reporting requirements for new federal programs. It also would require the president’s budget request to include, for programs that fail to report improper payments, an explanation of the obstacles that prevented such reporting.

According to a March 2024 GAO report, the federal government issued at least $236 billion in improper payments last year—that is, payments that shouldn’t have been made or were made in the wrong amounts. That’s more than the entire government spending of many countries, including Denmark, Israel, Switzerland, and South Africa.

The GAO noted that some programs—such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families and multiple rental assistance programs—failed to report their improper payments, so “the government-wide estimate potentially does not represent the full extent of improper payments.”

With 6.3% of federal government payments issued improperly, that’s equivalent to a typical household’s spending $4,600 on improper payments, out of an annual budget of $73,000.

(Note: My estimates of improper payment rates exclude spending and improper payments within Defense Department compensation because—although that information is included in the government’s payment reporting—compensation in all other government departments isn’t included in the data. Also, in keeping with references in reports by the White House Office of Management and Budget, this analysis uses the catchall term “improper payments” for those figures listed by the government as “improper and unknown payments.”)

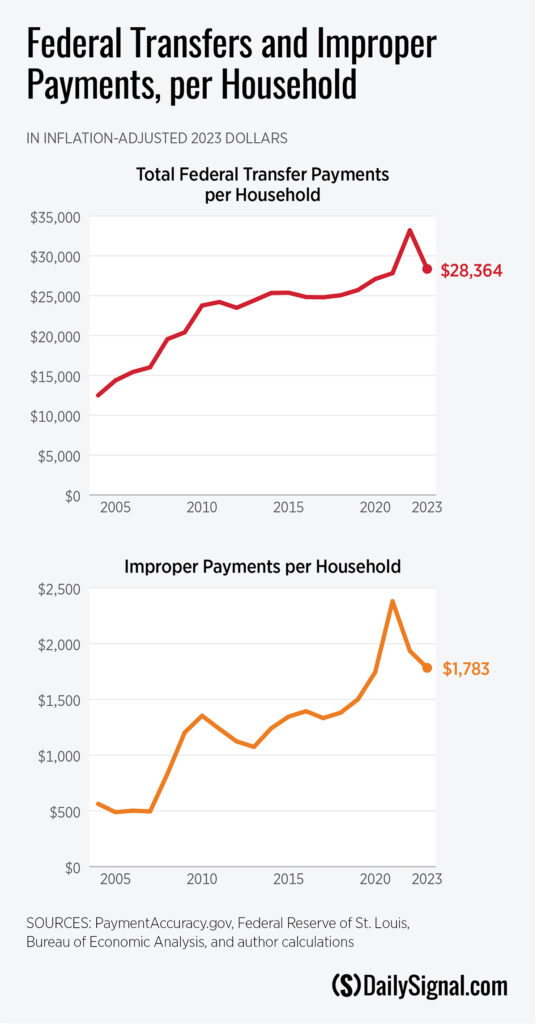

With the federal government spending over $28,000 per household per year in transfer payments, and almost $1,800 of that amounting to improper payments, American taxpayers deserve better.

Although Congress has passed well-intentioned and well-designed legislation to address improper payments, gaps and loopholes still exist.

For example, many agencies are required to issue report cards containing the amounts of improper payments, general causes, and action plans and evidence of progress. But those agency reports don’t identify specific failures and remedies or specific actions that Congress, the president, or other agencies must take so that the agency in question may reduce improper payments.

Moreover, a lack of enforcement amid agency failures remains the biggest loophole used to avoid accountability and integrity on this issue. Programs that repeatedly exceed 10% or even 30% in improper payment rates face zero consequences.

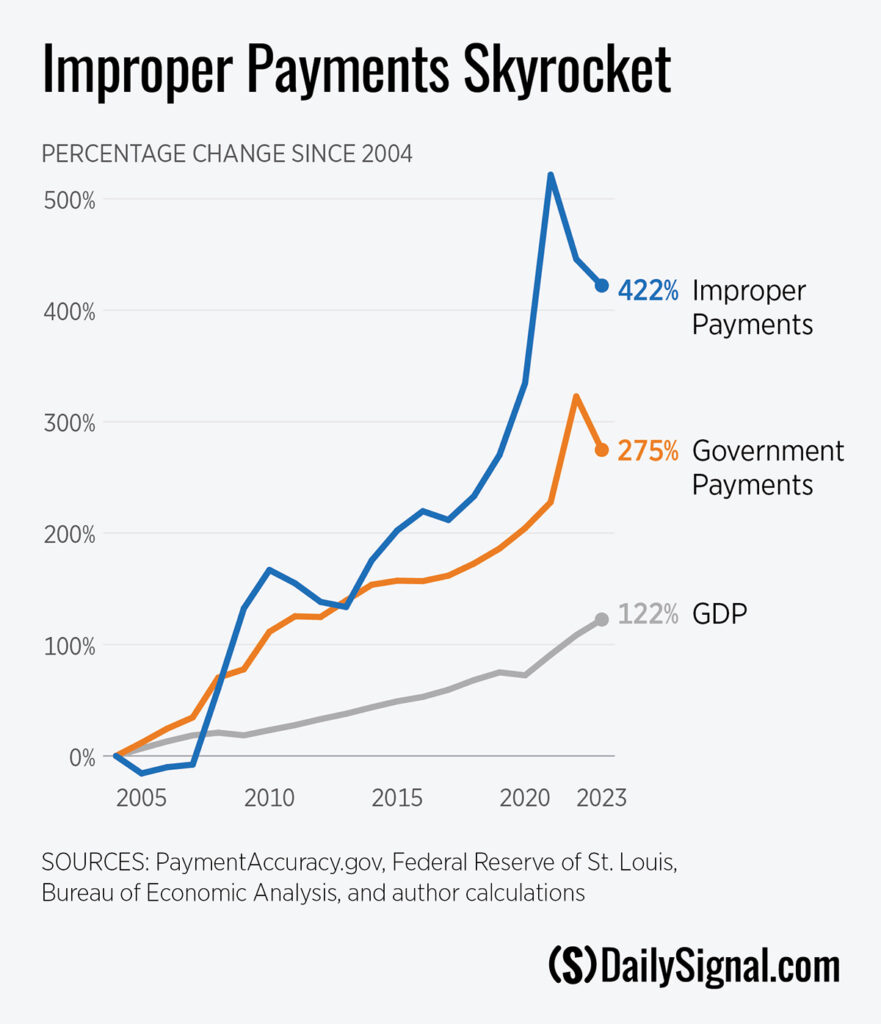

Massive, and generally rising, improper payments from the government reveal a major lack of integrity and accountability in agencies’ use of taxpayers’ money. The numbers reveal an even larger problem because of the massive explosion in size and scope of the federal government.

Since 2005, federal payments have increased at more than twice the rate of the gross domestic product; improper payments have grown three and a half times as much as GDP.

Reducing improper payments requires verifying identity and eligibility as well as imposing accountability—including consequences.

I’ve laid out dozens of recommendations to improve integrity and accountability across government programs, including the creation of a Taxpayer Integrity Office—TIO for short—within the Treasury Department to establish and enforce improved systems and procedures.

Although improper payments have grown so large that they necessitate their own line items and explanations in federal budgets, these payments are only a symptom of the disease of excessive government spending.

Policymakers should confront unsustainable national debt and budget deficits by restoring power and money to Americans. Every dollar taken out of the federal budget and restored to the budgets of American households will reap multifold returns.