International Energy Agency Promotes Oil Shortage Instead of Preventing It

Mario Loyola /

This year’s Conference of the Parties to the U.N. climate agreements, or COP, is being held in the Emirate of Dubai, arguably the world’s most extravagant display of oil wealth. Ironies abound. The host and president of this year’s conference, Sultan Ahmed al Jaber, happens also to be the CEO of the United Arab Emirates’ national oil company.

An embarrassing contretemps was inevitable and finally materialized on no less a subject than “net zero,” the COP’s essential objective of reducing global “greenhouse gas” emissions through a combination of reduced emissions and carbon sequestration.

“There is no science out there, or no scenario out there, that says that the phaseout of fossil fuel is what’s going to achieve 1.5 degrees Celsius,” said Al Jaber onstage recently, “unless you want to take the world back into caves.” Climate activists erupted in consternation, and immediately pointed to the International Energy Agency’s recent update of its “Net Zero Roadmap.”

The IEA was created in response to the OPEC oil embargo of 1973, which caused oil prices to quadruple amid crippling shortages. According to its founding text, the IEA’s purpose was to “promote secure oil supplies,” “meet oil supply emergencies,” and reduce “dependence on imported oil.” For decades, it served as a useful platform for data-gathering, analysis, and policy coordination among major economies, all with the purpose of making the world energy market more resilient to oil shocks.

But starting with the publication in 2021 of its “Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector,” IEA jumped on the climate bandwagon. As Executive Director Fatih Birol later proudly noted, the new report “quickly became our most viewed and downloaded publication ever.”

Whether out of a commitment to saving the planet, a desire to be feted by the climate jet set, or both, the IEA staff in effect abandoned its organic mission of protecting against oil scarcity and instead started promoting it.

Embracing the goals of the Paris Agreement on climate as its new mission, the IEA report laid out several scenarios for how things could go. These scenarios had several interesting features in common. First, they were all, to varying degrees, thoroughly implausible. More worrisome, if any of them were used as a policy guide to constrain fossil fuel production, the most likely outcome (other than windfall profits for oil companies) would be an energy crisis, and possibly an oil shock.

That worry has only grown since 2021, because (as could easily have been predicted) the world has fallen far short of the pace needed to achieve any of the scenarios. As a result, ever more drastic and desperate measures are being called for in order to get “back on track.”

In the most drastic Net-Zero Emissions scenario, the report called for no new oil and gas fields and no new coal mines starting immediately in 2021.

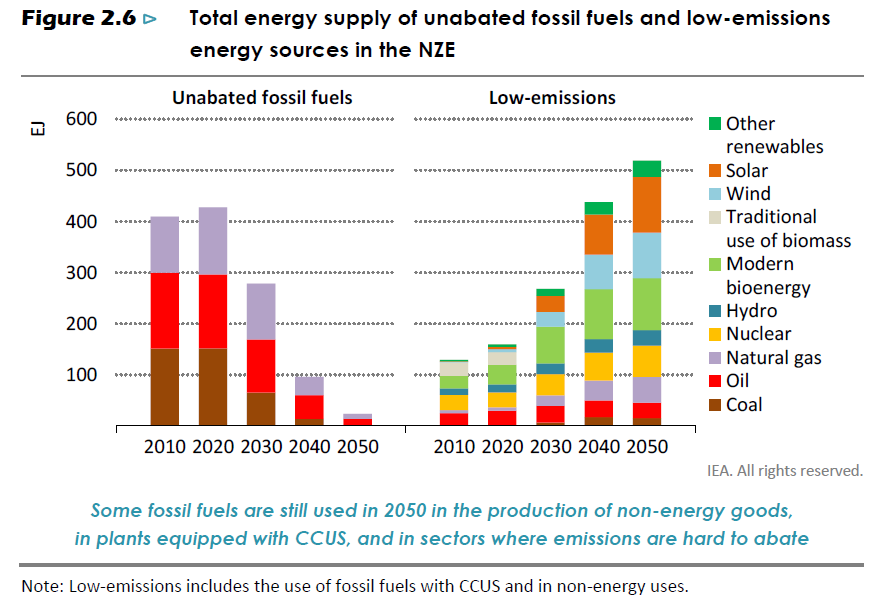

By 2030, all coal plants would be shuttered or operating on full carbon capture and storage (meaning all emissions would need to be captured before entering the atmosphere) and 60% of cars sold would be electric. The share of the overall world energy supply supplied by unabated fossil fuels (e.g., fossil fuels not tied to some carbon-capture scheme) would fall by about a third.

By 2035, no new gasoline-powered cars would be made and advanced economies would achieve net-zero electricity.

By 2040, global oil demand would be 50% of the 2020 low and unabated fossil fuels would be disappearing fast.

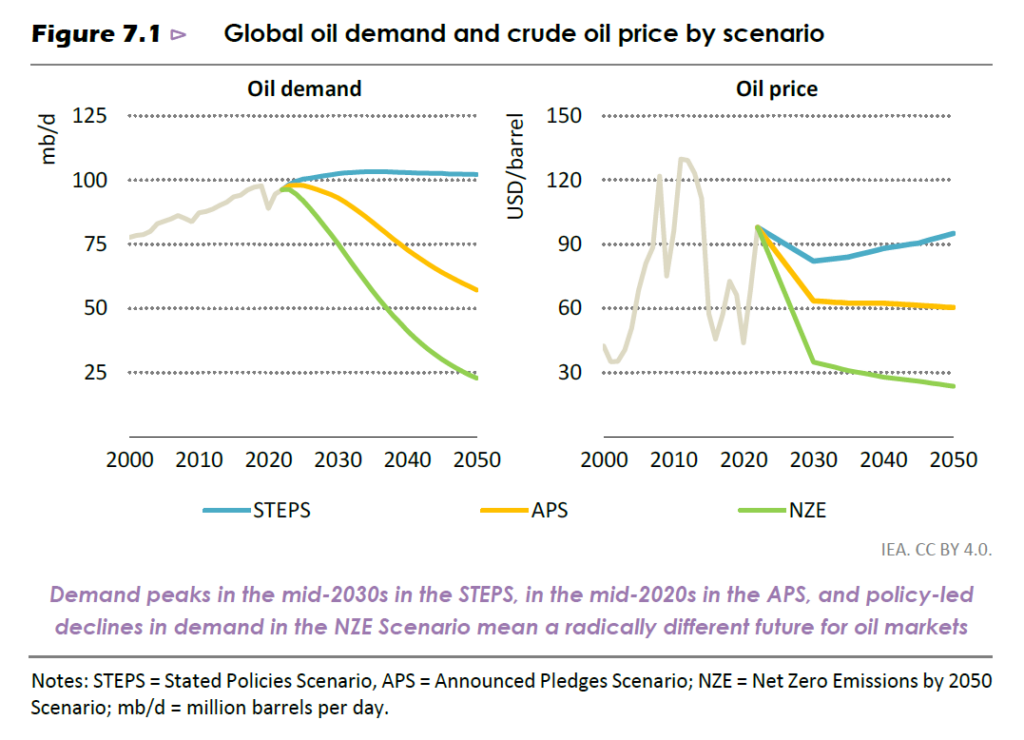

In the less drastic Announced Pledges Scenario, thanks to “stronger policy action,” the IEA projected that oil consumption would not return to its 2019 peak of 98 million barrels per day worldwide and would fall further.

This scenario, which assumes full implementation of all the pledges made under the Paris Agreement, would still “fall well short of what is necessary to reach global net-zero emissions by 2050,” which the IEA claims would lead to an average temperature rise of 2.1 degrees Celsius by 2100.

Even in the least drastic Stated Policies Scenario, oil peaks at around 104 million barrels per day shortly after 2030 and thereafter holds steady, while coal declines by 15% and temperatures rise 2.7 degrees Celsius by 2100. Even in this gloomy scenario, however, the IEA projected that overall carbon emissions would peak at 35 gigatons in 2030 and decline by a third among advanced economies, “thanks to the impact of policies and technological progress in reducing energy demand and switching to cleaner fuels.”

What Is the IEA’s New Role?

The IEA avoided calling explicitly for reductions in fossil fuel production in its 2021 report. But a reduction in production is heavily implied in its attributing the emissions reduction progress in various scenarios to “stronger policy action,” which is an obvious reference to oil producers’ reducing production.

Perhaps the most implausible aspect of the IEA scenarios is that they treat the development and availability of low-carbon substitutes such as wind and solar energy as the metric of success, such that fossil fuels are largely obviated, leading to demand for fossil fuels falling faster than supply. Hence, in the fantasy world of the IEA’s climate forecasts, the closer the world gets to net zero, the lower the price of fossil fuels.

This analytical sleight-of-hand has already infected the IEA’s “World Energy Outlook,” long a benchmark for energy analysts. In the 2022 edition, the following graph appears:

For an idea of how much LSD was in that Kool-Aid, consider just a few facts.

The Net-Zero Emissions scenario had oil demand dropping further from its pandemic low and reaching perhaps 80 million barrels per day by 2025. In fact, as the IEA more recently acknowledged, demand likely reached 102 million barrels per day in 2023, which is higher growth than in the Stated Policies Scenario.

More fantastical still, the Net-Zero Emissions scenario had oil prices falling precipitously from 2020 to 2030 and then dropping below $30/per barrel after that, which is not enough to cover costs for many or most producers.

So, not only was the IEA saying that renewables would be in plentiful abundance as substitutes for oil at current prices, it was saying that renewables would remain cost-competitive even with oil prices falling by about 70%.

There was an obvious problem with all three IEA scenarios. IEA had not even bothered to do the main thing it was supposed to do, which was to attempt an objective forecast of what scenarios were most likely.

The IEA treated the Stated Policies Scenario almost like a “no action” baseline (what in economic forecasting is often called a “base case”). However, not only is Stated Policies Scenario not a “no action” scenario, but achieving it would require changes in law so sweeping that it is only slightly less implausible than the sheer science fiction of the Net-Zero Emissions and Announced Pledges scenarios.

Take the United States, for example. Here, part of the “stated policy” is President Joe Biden’s plan to achieve net-zero electricity by 2035.

At an IEA briefing at last year’s Conference of the Parties in Egypt, I asked IEA staff whether there was any attempt to assess the feasibility of any of the stated policies. As reported at the time by Reason magazine, I pointed out that, as far as the U.S. was concerned, the stated policy was an “absolute fantasy.”

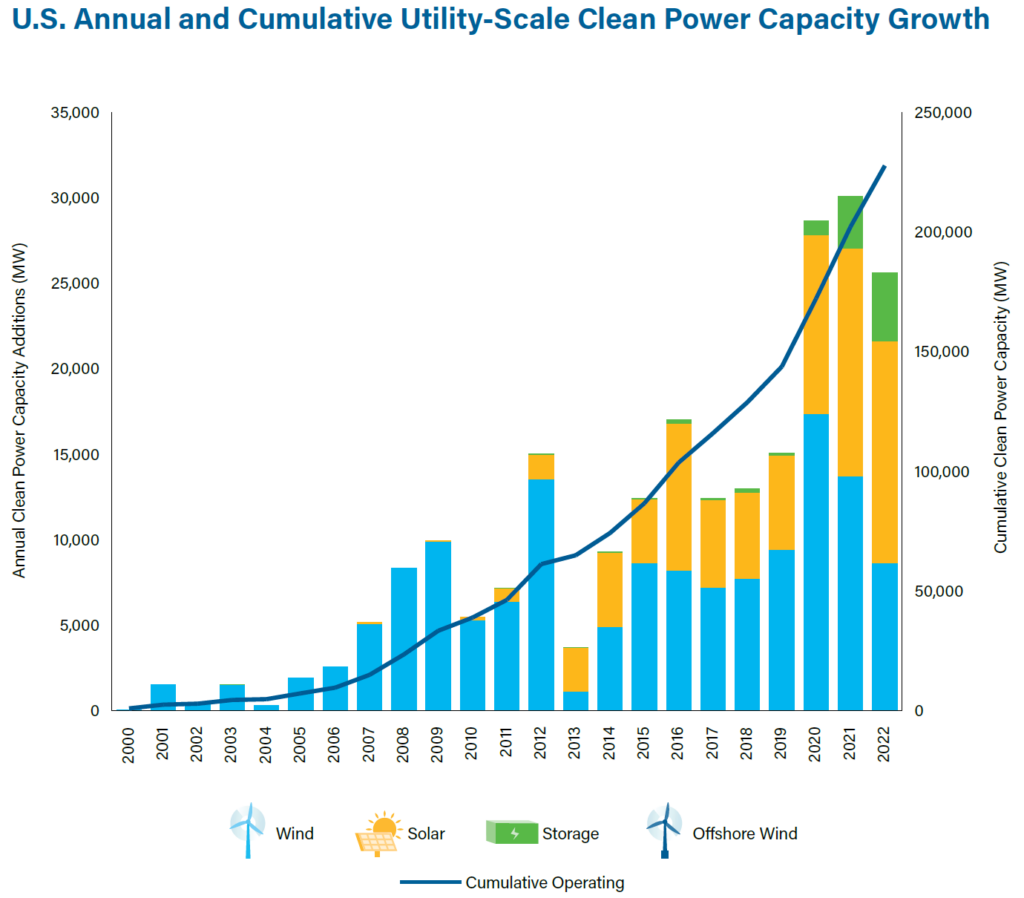

I explained that the red tape involved in obtaining required federal permits for energy infrastructure is a virtually insurmountable obstacle to building renewable energy infrastructure at the scale and speed that would be required to achieve net-zero electricity by 2035.

IEA staff answered that this was indeed a problem that they had discussed, but they couldn’t second-guess stated policy for fear of contradicting the governments on the IEA’s Governing Board.

A year on, Congress has done little to fix the bottleneck in permitting energy infrastructure. As a result, there is a severe constraint on the amount of renewable electricity capacity that can be permitted in a given year.

In no year has the amount permitted been anywhere near the pace that would be required to meet Biden’s goals. Indeed, partly because Biden rescinded the Trump-era reforms, the amount of renewable electricity capacity permitted in 2022 was 10% lower than in 2020, the last year of the Trump administration.

The American Clean Power Association explains some of the reasons why: “Supply chain constraints, lengthy delays connecting projects to the grid, unclear trade restrictions, long-standing permitting obstacles, and uncertainty over IRA [Inflation Reduction Act] implementation hindered project development and investment activity.”

Crash Landing the Global Economy Into Compliance With the Paris Agreement

Biden’s proposed electric vehicle and power plant mandates are an attempt to crash-land the U.S. transportation and power sectors into compliance with the Paris Agreement. If implemented, there will certainly be a crash.

By choking off the production of gas-powered vehicles and fossil fuel-based electricity generation before renewable substitutes are cost-competitive and available, the regulations would cause a catastrophic scarcity crisis in both the transportation and power sectors. The crisis would be grossly regressive, falling hardest on the most vulnerable.

In the recently released 2023 update to its “Net Zero Roadmap,” the IEA continues to treat supply reductions as if they are really demand reductions. For example, says the IEA update, “Well-designed policies, such as the early retirement or repurposing of coal-fired power plants, are key to facilitate declines in fossil fuel demand and create additional room for clean energy to expand.”

The same conflation of supply and demand is now driving the latest controversy at the Conference of the Parties, as governments negotiate furiously over draft text that would “phase out fossil fuels in line with best available science” or language to similar effect. Some have described the purpose as phasing out fossil fuel “use,” but as details emerge, it is becoming clear that what most people at the conference have in mind is phasing out fossil fuel production.

The difference, as even the IEA would acknowledge, is that cutting fossil fuel “use” means reducing demand, leading to lower prices, whereas cutting fossil fuel “production” means reducing supply, which can only raise prices.

Countries can reduce demand for fossil fuels in a variety of ways, from technology-driven reductions in energy intensity across the economy to developing cost-competitive renewable substitutes to forced rationing (e.g., government-created scarcity on the demand side).

Any of these lower the price for oil and gas—though they also lower the price at which renewables have to be cost-competitive, creating new difficulties for any clean up energy transition. But cutting production would mean catastrophic energy scarcity, or “taking the world back into caves,” in the memorable words of Al Jaber.

Getting the IEA Back on Track

Whether the Conference of the Parties will agree to create an energy crisis, as some of the proposals would certainly do, remains to be seen. One thing we know for sure is that such an agreement would be totally contrary to the mission of the IEA.

The IEA’s original purpose included development of alternative energy sources. But that was in order to protect against future oil shocks, not to create a transition to alternative sources at the risk of an oil shock.

The U.S. has the lion’s share of voting rights on the IEA’s Governing Board. Those voting rights should be used to fire the current executive director and replace him with somebody who will stick to the IEA’s actual mission in the real world.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email letters@DailySignal.com, and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the URL or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.