The Trump administration has re-designated North Korea as a state sponsor of terrorism. It’s a proper and pragmatic, if belated, acknowledgement that North Korea’s repeated, deadly actions legally constitute terrorist acts under U.S. law. As President Donald Trump commented, “It should have happened years ago.”

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson announced the re-designation was to “hold North Korea accountable for a number of actions that they’ve taken [and is] the latest step in a series of ongoing steps [taken by the administration] to increase the pressure on the North Korean regime.”

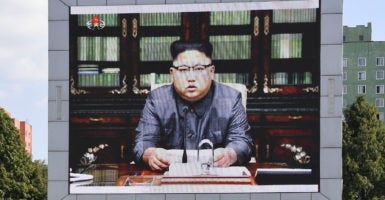

The U.S. action aims to further reduce foreign entities’ willingness to do business with Kim Jong Un’s heinous regime. This would tangibly hamper Pyongyang’s ability to finance its destabilizing activities. While global attention has focused on North Korea’s pursuit of nuclear weapons, we must not lose sight of its terrorist activities and gross violations of human rights.

The United States placed North Korea on the State Sponsors of Terrorism list in 1988 after North Korean agents blew up a South Korean commercial airliner, killing 115 people. Twenty years later, the George W. Bush administration removed Pyongyang from the list in a failed attempt to improve the atmosphere for progress in the Six-Party Talks nuclear negotiations. But the talks collapsed soon afterward over North Korea’s rejection of verification protocols.

U.S. law, such as 18 U.S. Code § 2331, defines international terrorism as acts that:

involve violent acts or acts dangerous to human life that are a violation of the criminal laws of the United States … appear to be intended to intimidate or coerce a civilian population, to influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion, or to affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping; and occur primarily outside the territorial jurisdiction of the United States.

Kim’s regime has checked every box.

Since being dropped from the terrorism list, Pyongyang has conducted repeated cyberattacks against government agencies, businesses, banks, and media organizations. It has also engaged in: threats of “9/11-type attacks” against U.S. theaters and theatergoers; assassination attempts against North Korea defectors, human rights advocates, and South Korea intelligence agents; and numerous shipments of conventional arms bound for terrorist groups Hamas and Hezbollah. Earlier this year, North Korean agents used VX, the most deadly nerve agent, to kill Kim’s half-brother in a crowded civilian airport.

Returning North Korea to the terrorist list enables Washington to invoke stronger financial transaction licensing requirements under 31 CFR Part 596 and remove North Korea’s sovereign immunity from civil liability for terrorist acts. Re-designation also requires the U.S. government to oppose loans to North Korea by international financial institutions, such as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and Asian Development Bank.

Moreover, the designation adds to the moral suasion of international efforts to further isolate North Korea—diplomatically as well as economically. In recent years, a growing list of countries, banks, and companies have curtailed their business relationships due to North Korea’s violations of U.N. resolutions, the abysmal working conditions imposed on its overseas laborers, and its human rights violations, which the U.N. says constitute “crimes against humanity.”

Numerous foreign entities are suspending economic deals, curtailing North Korean worker visas, and ejecting North Korean diplomats. Designating North Korea as a state sponsor of terrorism could induce additional business partners to sever their ties to the regime.

Some will argue that re-designating North Korea won’t solve the North Korean nuclear issue or could trigger a harsh regime response, such as more nuclear and missile tests or a military attack. But it is only a matter of time before Pyongyang conducts such tests to complete development of its programs and demonstrate its ability to threaten the United States and its allies with nuclear weapons.

Similar worries were expressed after every U.N. resolution condemning Pyongyang. They were voiced, too, when the U.N. Commission of Inquiry concluded in 2014 that Pyongyang’s human rights violations were so atrocious, widespread, and systematic as to legally constitute “crimes against humanity.” But to hesitate would be to turn a blind eye to the nature of the regime. Such concerns amount to little more than a call to not enforce U.S. law because the criminal might object.

As to complaints that the re-designation will complicate returning to nuclear negotiations, North Korea has declared—repeatedly and emphatically—that the Six-Party Talks are dead. It has further vowed that it will never abandon its nuclear arsenal. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for East Asia Joseph Yun stated that, despite repeated U.S. attempts to engage North Korea, “we had no communication from them … we have no signal from them.”

The most effective time to engage in negotiations would be after a comprehensive, rigorous, and sustained international pressure campaign. Such a policy upholds U.S. laws and U.N. resolutions, imposes a penalty on those who violate them, makes it more difficult for North Korea to import components—including money from illicit activities—for its prohibited nuclear and missile programs, and constrains proliferation. Re-designating Kim’s regime as a state sponsor of terrorism ramps up the pressure—and is long overdue.