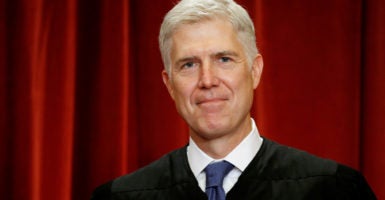

The newest Supreme Court justice, Neil Gorsuch, has made headlines since joining the court last spring—and not just for his written opinions. Pedantic. Boorish and juvenile. Annoying. In his colleagues’ faces. These are some of the harsh things liberal Court watchers have had to say about Gorsuch.

It’s hard to square these comments with the outpouring of support Gorsuch received from former clerks, classmates, and others after he was nominated to the Supreme Court earlier this year. Just watch a few minutes of this speech by Mark Hansen, Gorsuch’s former law partner, who was close to tears at the end, talking about what an honorable, decent (and whip smart) friend and colleague he has been:

But the left would have you believe otherwise.

In a recent episode of the Supreme Court podcast “First Mondays,” NPR’s legal affairs correspondent Nina Totenberg took aim at Gorsuch. First in her crosshairs was his habit of frequently citing the Constitution. She objected to Gorsuch bringing things back to first principles at oral argument. He often prefaces his questions by saying, “Let’s look at what the Constitution says about this … It’s always a good place to start.” This should come as no surprise.

When rumors were swirling about potential Supreme Court nominees in late 2016, a former Gorsuch clerk wrote on Yale’s Notice & Comment blog: “Whenever a constitutional issue came up in our cases, he sent one of his clerks on a deep dive through the historical sources. ‘We need to get this right,’ was the memo—and right meant ‘as originally understood.’”

As a member of the Supreme Court, Gorsuch is putting these principles into practice and fulfilling his commitment to faithfully interpret the Constitution according to its original public meaning.

And that’s not all Totenberg had to say about Gorsuch. She claimed there is a rift on the court between Gorsuch and Justice Elena Kagan. Here’s what she said:

My surmise, from what I’m hearing, is that Justice Kagan really has taken [Gorsuch] on in conference. And that it’s a pretty tough battle and it’s going to get tougher. And she is about as tough as they come, and I am not sure he’s as tough—or dare I say it, maybe not as smart. I always thought he was very smart, but he has a tin ear somehow, and he doesn’t seem to bring anything new to the conversation.

First, I’m highly skeptical of someone purporting to know what happened when the court met in conference. The justices are notoriously secretive about these meetings—not even law clerks are allowed in the room. During conference, the justices discuss cases following oral argument and cast their initial votes in conference, though they sometimes change after draft opinions have been circulated. This is precisely the time for the justices to debate the issues in a case.

Second, Totenberg’s assertion that Gorsuch is “maybe not as smart” as she thought is off base. Anyone who has read his speeches or his written opinions—either from his time on the appeals court or his first two months on the Supreme Court—can see why that is patently false. The Columbia-Harvard-Oxford-educated judge weaves literary references into his opinions and writes in a clear, concise manner that’s easy for lawyers and lay people alike to understand.

Totenberg also said she hears Gorsuch “doesn’t believe in precedent”—which is likely motivated by a concern that he would overturn cases liberals like if given the chance. This same issue came up during his confirmation hearing, when Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., grilled Gorsuch about his views on the “superprecedent” status of Roe v. Wade. During the hearing, Gorsuch explained several factors that judges weigh when deciding whether an old decision is still good law.

He even wrote a book on this topic, along with 11 other judges and leading lexicographer Bryan Garner. And he’s given every indication that he’ll follow the Supreme Court’s guideposts for when to overrule or uphold a past decision. It’s also worth mentioning that, even if he disagreed with a past decision, Gorsuch can’t singlehandedly overturn precedents like Roe v. Wade. If an appropriate case came before the court, a majority of the justices would need to agree.

Gorsuch rubs Totenberg the wrong way—and she isn’t the only one.

At the start of the court’s current term, Jeffrey Toobin wrote an article for The New Yorker taking issue with Gorsuch “dominat[ing] oral arguments, when new Justices are expected to hang back” and writing dissents in his first couple months on the job.

Toobin highlighted a case involving statutory interpretation where Gorsuch dissented from the majority’s reading of the statute. Gorsuch wrote, “If a statute needs repair, there’s a constitutionally prescribed way to do it. It’s called legislation.” What Toobin objected to are basic functions of the job—if justices aren’t to ask questions at argument or write separately when they disagree with the majority, what are they supposed to do?

In an article in The New York Times over the summer, Linda Greenhouse—who referred to Gorsuch as “the justice who holds the seat that should have been Merrick Garland’s”—said the new justice violated the court’s unwritten rules and norms and “morph[ed]… quickly into Donald Trump’s life-tenured judicial avatar.” This gets to the heart of the problem.

According to the left, Gorsuch shouldn’t be on the Supreme Court, and Trump shouldn’t be in the White House. In other words, these criticisms of Gorsuch can be explained as simply another iteration of the resistance movement.

But Gorsuch isn’t going anywhere. The apoplectic left better get used to him sparring with the other justices, asking questions, writing fiery dissents, and generally returning to first principles.