“Do you consider yourself an orthodox Catholic?” is an unusual and inappropriate question for a senator to ask a judicial nominee. In fact, the Constitution forbids it.

But that didn’t stop Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., from probing Notre Dame Law professor Amy Coney Barrett about her faith. Sen. Dianne Feinstein. D-Calif., also chided Barrett for being a practicing Catholic, proclaiming, “The dogma lives loudly within you, and that’s of concern.”

Both senators appear to have forgotten Article VI’s admonition that “no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Officer or public Trust under the United States.”

The senators’ hostility to religion was loudly on display as Barrett and Michigan Supreme Court Justice Joan Larsen appeared before the Senate Judiciary Committee Wednesday, having been nominated by the president to fill two federal appellate vacancies.

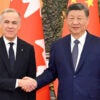

President Donald Trump nominated Larsen for the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Michigan and Barrett for the 7th Circuit in Indiana. Both women have faced bitter scrutiny from the left. This makes sense, as both are brilliant, young, conservative, and female, making them serious contenders for a future Supreme Court vacancy.

After a delay, Democratic senators from both Michigan and Indiana have returned the nominees’ blue slips, allowing their nominations to move forward.

But just who are Larsen and Barrett?

Joan Larsen

It came as no surprise when Trump tapped Larsen for a seat on the 6th Circuit. She was one of 21 individuals on the list of judicial rock stars he used to fill the last Supreme Court vacancy.

A graduate of Northwestern University Law School, Larsen clerked for Judge David Sentelle on the D.C. Circuit and for Justice Antonin Scalia on the Supreme Court. When asked what it was like to be a woman clerking for Scalia, she has often quipped, “Much like being a man clerking for him.”

In 1998, Larsen became an adjunct professor at the University of Michigan Law School, where she taught constitutional law, criminal procedure, presidential power, and statutory interpretation.

Her academic career was interrupted by brief stints in private practice and as a deputy assistant attorney general in the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel.

In September 2015, Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder appointed her to the state Supreme Court. Although Larsen has a relatively thin judicial record due to her short tenure on the court, she has made her views about judging very clear.

When Snyder appointed her, she stated, “I believe in enforcing the laws as written by the legislature and signed by the governor. I don’t think judges are a policy-making branch of the government.”

This is right in line with how her former boss, Scalia, viewed judging. Shortly after Scalia’s death, she penned an op-ed for The New York Times in which she wrote: “Justice Scalia believed in one simple principle: That law came to the court as an is not an ought. Statutes, cases, and the Constitution were to be read for what they said, not for what the judges wished they would say.”

In her 2016 retention election, she again made her views clear, writing:

Judges are supposed to interpret the laws; they are not supposed to make them. The separation of powers, enshrined in both our national and state constitutions, protects the people’s right to self-governance by allowing the elected representatives of the people to make the laws. Judges, like everyone else, are bound by those laws and must faithfully interpret them rather than re-writing them from the bench. Judges, after all, are the public’s servants, not the public’s masters.

Larsen has received an outpouring of support for her nomination, including endorsement letters from 32 University of Michigan law professors and former colleagues and 29 former government officials and colleagues.

During the hearing, she faced questions about her time at the Department of Justice and about a controversial memo that set forth a justification for enhanced interrogation techniques, including waterboarding. But Larsen was not involved in researching or drafting that memo.

She also faced questions from senators about the role of legal precedents, as well as a 2004 law review article in which she criticized the use of foreign and international law in interpreting our Constitution.

Amy Coney Barrett

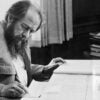

Like Larsen, Barrett has a sterling resume. After graduating from Rhodes College and Notre Dame Law School, Barrett clerked for Judge Laurence Silberman on the D.C. Circuit and for Scalia on the Supreme Court.

She then worked in private practice (where she was part of the team that represented George W. Bush in Bush v. Gore) before starting her career in academia, teaching briefly at George Washington University and the University of Virginia before joining the Notre Dame Law faculty in 2002.

She teaches constitutional law, federal courts, statutory interpretation, civil procedure, and evidence. Notre Dame twice recognized her as distinguished professor of the year.

Barrett is also a prolific writer, having published in leading law reviews across the country on topics including originalism, federal court jurisdiction, and the supervisory power of the Supreme Court.

In 2010, Chief Justice John Roberts appointed her to the Advisory Committee for the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, where she served for six years.

Barrett has robust bipartisan support from the legal community. Shortly after her nomination, endorsement letters poured in to the Judiciary Committee from lawyers across the political spectrum, including 450 former students, 49 Notre Dame law colleagues, and every fellow Supreme Court clerk that served with her.

The Judiciary Committee also received an endorsement letter from 73 law professors from across the country who called Barrett’s qualifications “first-rate,” including Neal Katyal, a prominent liberal who served as President Barack Obama’s acting solicitor general.

Barrett faced numerous questions about her writings, including her criticism of stare decisis or the role of precedent in judicial decision-making in certain circumstances.

For example, she has questioned the practice of judges relying on precedent when it conflicts with the original meaning of the Constitution’s text. Justice Clarence Thomas has also questioned the role of precedent in these circumstances.

She assured the committee, however, that as an appellate judge, she would follow all Supreme Court precedents, which are binding upon all lower court judges.

She also faced questions about a 1998 article that she co-authored as a law student, discussing Catholic judges participating in death penalty cases. In that article she considered situations in which the law and a judge’s religious faith conflict.

Senate Democrats attempted to distort her article, claiming she would put religious beliefs above the law. But in fact, she wrote, “The legal system has a solution for this dilemma—it allows (indeed it requires) the recusal of judges whose convictions keep them from doing their job.”

Barrett is not the first to broach this subject. Many Catholic judges have considered and written on this issue, including Judge William Pryor, who sits on the 11th Circuit, and Scalia.

Despite the tough questions they received, these two polished and accomplished women answered intelligently and gracefully. They both subscribed to the view that judges should not, under the guise of statutory or constitutional interpretation, impose their own policy preferences on the rest of society.

To date, the Senate has confirmed only six of Trump’s judicial nominees (including Justice Neil Gorsuch). But hearings are starting to pick up. Counting Larsen and Barrett, the Senate Judiciary Committee will hold hearings for six nominees this week.

With a stunning 162 current and known future vacancies and 32 nominees pending, let’s hope the Senate keeps it up.