The ongoing controversy about the federal government’s role in managing land may soon come to a head.

Earlier this month, in accord with a presidential executive order issued in April, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke delivered recommendations to the president on national monument lands that are being reviewed by his department.

Details about the report—whether lands should be reduced, and if so, which ones—are expected from the White House in the coming days.

The highly anticipated report has stirred a great deal of angst this summer, particularly among environmental activists who are convinced the Interior’s review is an unprecedented ploy to sell off or sully federal lands.

For example, luxury outdoor retailer Patagonia argued the following in its first ever television ad: “Public lands have never been more threatened than right now because you have a few self-serving politicians who want to sell them off and make money.”

Beautiful scenes of the Grand Tetons, Yosemite, and Zion pan across the screen as the company urges viewers to defend these lands and hold Zinke accountable.

The Patagonia commercial and much of the conversation this summer have been muddled with hyperbole and misinformation. It’s worth taking a step back to understand the issue.

Who’s Involved

In April, President Donald Trump requested that Zinke review all presidential national monument designations or expansions since 1996. In particular, Trump requested review of designations of areas over 100,000 acres and/or those that were “made without adequate public outreach and coordination” to determine if revisions were necessary.

Other presidents have reviewed and altered national monuments—among them Presidents William Howard Taft, Woodrow Wilson, Calvin Coolidge, Harry Truman, and Ike Eisenhower.

What’s at Issue

The subject of Interior’s report is presidential use of the Antiquities Act of 1906. The law allows presidents to unilaterally designate federal lands as “historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest.” These designations change how land is managed and who has access to it.

Trump is considering the need to reduce the size of, or altogether eliminate, some of these monuments.

Contrary to what the Patagonia commercial and many others would imply, reducing the size of a national monument or even rescinding its status does not open up the federal land to be overrun by oil interests or clear cut by the foresting industry.

Federal lands are managed by a web of laws determining who can do what and when. For example, at least nine other laws also address artifact preservation on federal lands.

The Lands in Question

Perhaps where environmental groups most mislead the public is in explaining which lands are being reviewed. National monuments are distinct from other land designations like national parks, which are created by Congress.

Zinke’s review covered 27 national monuments, mostly in the western United States, though some are located in New England and in offshore federal waters. In other words, this debate has nothing to do with the Grand Tetons, Yosemite, or Zion—all of which are national parks.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that the federal government owns hundreds of millions of acres in America. To put that in perspective, that’s about the same size as all of Western Europe. (See Congress’ official map of federal lands below.)

Why Trump’s Upcoming Decision Matters

The reason this 110-year-old law has become so contentious is complicated.

In part, it has to do with past presidents abusing the purpose of the law. The Antiquities Act directs the president to protect artifacts on federal lands according to the “smallest area compatible with proper care and management of the objects to be protected.”

However, in recent history the Antiquities Act has instead been used to pull vast swathes of land out of use.

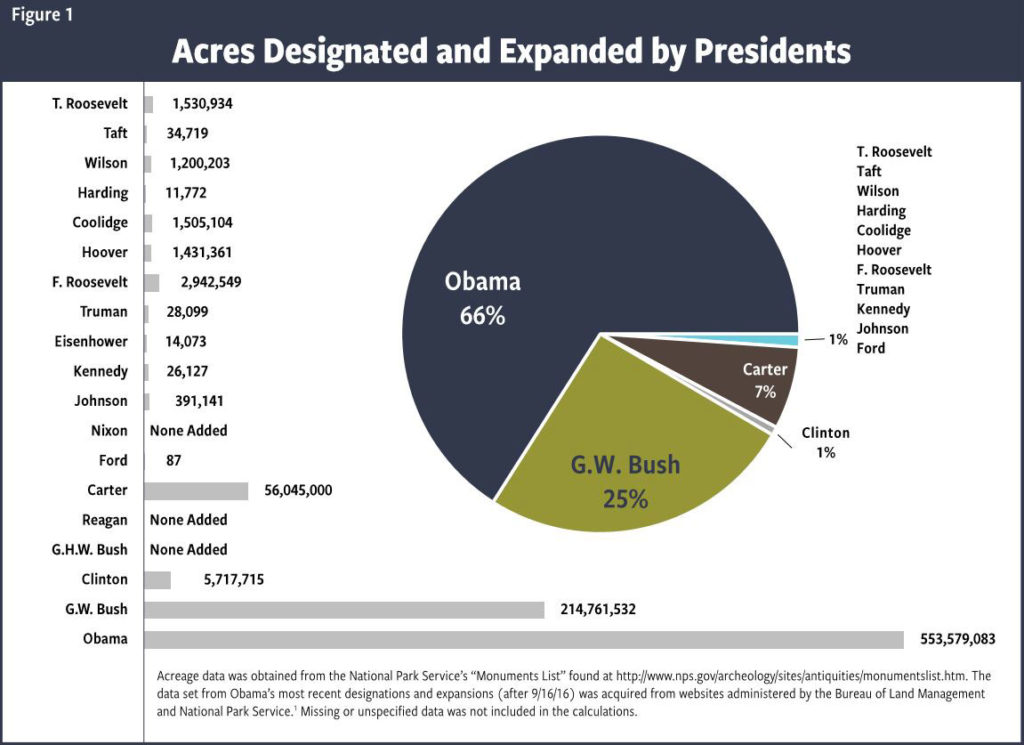

President Barack Obama in particular used this power aggressively. The Sutherland Institute reports that 66 percent of all national monument acreage was designated so under the Obama administration, and 25 percent under President George W. Bush.

It also has to do with ensuring quality management of lands. It is no secret that the Department of Interior is facing $15.4 billion in maintenance backlogs, and $11.9 billion of that is in the National Park Service alone.

Holly Fretwell of the Property and Environment Research Center reports that “[o]nly 40 percent of park historic structures are considered to be in “good” or better condition and they need continual maintenance to remain that way.”

The “why” also has to do with who should get the most say in decision-making.

The Patagonia ad encourages people to oppose changes to national monuments because “this [land] belongs to all the people in America—it’s our heritage.” But this glosses over decades and generations’ worth of contentious debate about who “our” refers to.

Does it refer to fly fishermen, hunters, hikers, and bikers as Patagonia would have its customers believe? Does it refer to the Native Americans and locals who are directly impacted by federal land management decisions, but who have little say in the matter?

Are American natural resource industries to be excluded from the collective “our”?

If Congress doesn’t like what the Trump administration is doing, it ought to act to clarify the law. Zinke rightly noted that “the executive power under the Act is not a substitute for a lack of congressional action on protective land designations.”

At the very least, Congress ought to amend the law to give states more say in the matter.

Land management decision-making has been contentious for decades. Shifting more control from Washington to those with direct knowledge of the land in question and a clear stake in the outcome of decisions would be a step in the right direction.