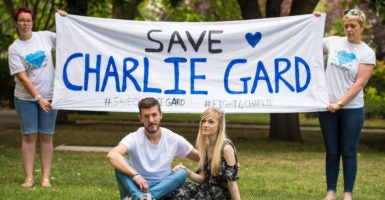

For weeks, the world has been watching in rapt attention the saga of Charlie Gard—the case involving a desperately ill child fighting for survival in the face of U.K. government efforts to block treatment.

Charlie’s parents have been relentless in fighting the government and seeking help abroad.

Their efforts are already bearing fruit. Most recently, a judge has agreed to re-evaluate a previous decision barring the parents from seeking alternative treatment for their son in the United States.

Here at home, opinions differ, but the general reaction is one of outrage that a government official could make a decision about what’s best for a child over the objections of the child’s parents, combined with a sense of relief that this is not the status quo in the United States.

Unfortunately, this is not quite accurate.

Under a little-known regulation referred to as “certificate of need,” a majority of states actually place unelected government officials in the position of deciding what types of medical facilities and treatment options are available in local communities.

While the Charlie Gard case involves other issues as well, government intervention in care is at the heart of the dispute.

And under certificate of need laws, any provider that wants to expand certain types of facilities and medical technology or purchase additional equipment must first ask the state for permission.

>>> The Tragic Case of Charlie Gard Highlights the Importance of Parental Rights

The original rationale for these regulations was to prevent providers from competing with one another based on the size or luxuriousness of their facilities, and then passing the cost for those bells and whistles down to their patients.

Lawmakers were also assured by many community hospitals that the institutions would be able to provide more charity care to the uninsured and underinsured because those efforts would be subsidized by wealthier patients who would have no choice but to use the community hospitals.

However, research has shown that states with certificate of need laws actually have more expensive health care and provide a lower quality of medical services.

Additionally, many of the hospitals in certificate of need states do not provide additional charity care as a result of the laws. Instead, the laws end up protecting local monopolies by allowing providers to charge more for less service.

Things have gotten so bad that under successive administrations of both parties, the Federal Trade Commission has sent letters to states urging them to end their certificate of need programs because they are anticompetitive.

Most states have ignored this sound advice, sometimes with devastating consequences.

One heartbreaking example includes the case of a prematurely delivered infant dying while waiting for transport because the hospital where the child was born lacked a neonatal intensive care unit, and doctors needed an incubator to stabilize the newborn.

The twist, however, is that just a few years prior, the hospital’s request to build such a unit was rejected by Virginia on the basis that it was “not in the best health interests of the community”—a chilling precursor of the British Supreme Court decision that denied Charlie treatment because it determined it was “not in his best interests.”

The biggest difference between the high-profile case in the U.K. and certificate of need programs in the United States is that most of us never realize that the government has denied us access to certain health care options.

For lawmakers in certificate of need states tweeting about the ills of the U.K. health care system, now is the time for some serious introspection about how our own state governments are getting in the way of improved patient care.

The lives of their constituents might depend on it.