The Congressional Budget Office released its score on Monday of the Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017.

The top-line score is very similar to the American Health Care Act that was passed earlier in the House.

This budgetary analysis projects that if passed into law, the Better Care Reconciliation Act would reduce the number of insured by 22 million, but would decrease the deficit by $321 billion while also reducing federal outlays by $1,022 billion and federal revenue by $701 billion.

The Senate bill differs from its House counterpart in that it modifies the Obamacare tax credits rather than creating an entirely new tax credit. While it seems that the effects might be similar, the CBO states that average premiums in 2019 would be slightly higher in the Better Care Reconciliation Act due to larger subsidies for older people.

The CBO also includes the caveat that out-of-pocket costs could increase in states. However, in 2020, average premiums would be about 30 percent lower than under current law, and about 20 percent lower by 2026.

The CBO suggests that few low-income people would purchase plans under this scheme, as they believe higher deductibles and out-of-pocket costs will push people away from gaining coverage.

While total coverage losses work out to be roughly the same as the House bill, it is clear that on the insurance side, the effects of the law may be felt by different people.

One group, for example, are individuals that are not eligible for Medicaid, but under current law are also not eligible for exchange subsidies. The Senate health care bill extends subsidies to this group, meaning they receive assistance when they previously were on the hook for the full cost of their premiums.

This calculation could vary across individuals and states because of the uncertainty when it comes to waivers.

The new CBO score also addresses the effect of allowing states to pursue waivers in order to address their insurance programs.

It finds that premiums would likely be lower in states that pursue waivers, and while it provides some illustrative examples, the magnitude of these changes are highly dependent on state-level factors that are very difficult to score.

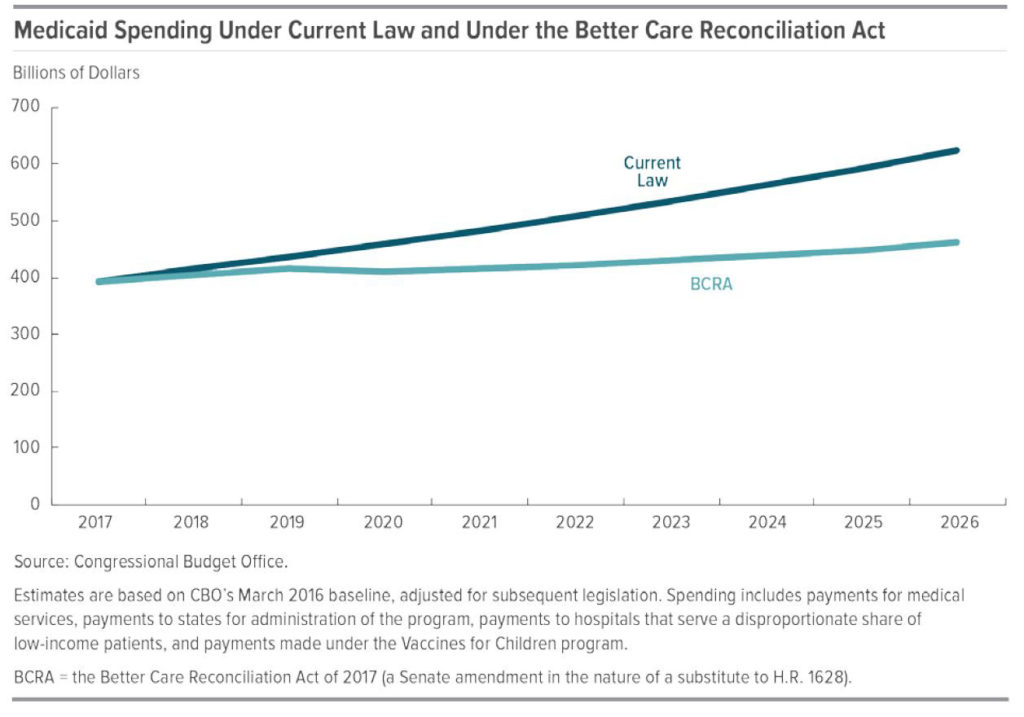

Once again, one of the main drivers in savings comes from the changes to Medicaid. The health care bill cuts $772 billion from Medicaid by 2026.

While the bill saves less than its House counterpart on Medicaid—mostly due to higher spending in the early years—it is clear that the budgetary effects still serve to put Medicaid on a budget.

While this includes rolling back the exclusion, there are also additional savings such as targeting gaming of the Medicaid reimbursement through provider taxes.

Key Takeaways

The CBO’s score of the Better Care Reconciliation Act has not changed much from the previous scores of the House bills.

While there might be disagreements about the coverage effects of state waivers, it is still clear that there are meaningful premium reductions from allowing states to pursue them.

The CBO still leaves many questions about the effects of this legislation open-ended. There are many difficulties and uncertainties in scoring any piece of health care legislation. When state-level decisions are also included, this becomes an even more difficult task.

Additionally, the CBO was asked to score this legislation with a quick turnaround time. The score likely would have provided more clarity if given extra time.

The CBO has also still failed to walk back its overly optimistic views on the effectiveness of the individual mandate and the performance of Obamacare moving forward.