COLEBROOK, N.H.—Bruce Latham, a lanky, self-employed doctor, occupies a unique position in the depths of rural New Hampshire’s opioid drug addiction crisis.

As part of his practice in Colebrook, a town of 2,300 in Coos County, Latham responds to pain by prescribing opioid painkillers. He says he empathizes with patients’ propensity to become addicted to pain medicine because his own son is a recovering drug addict.

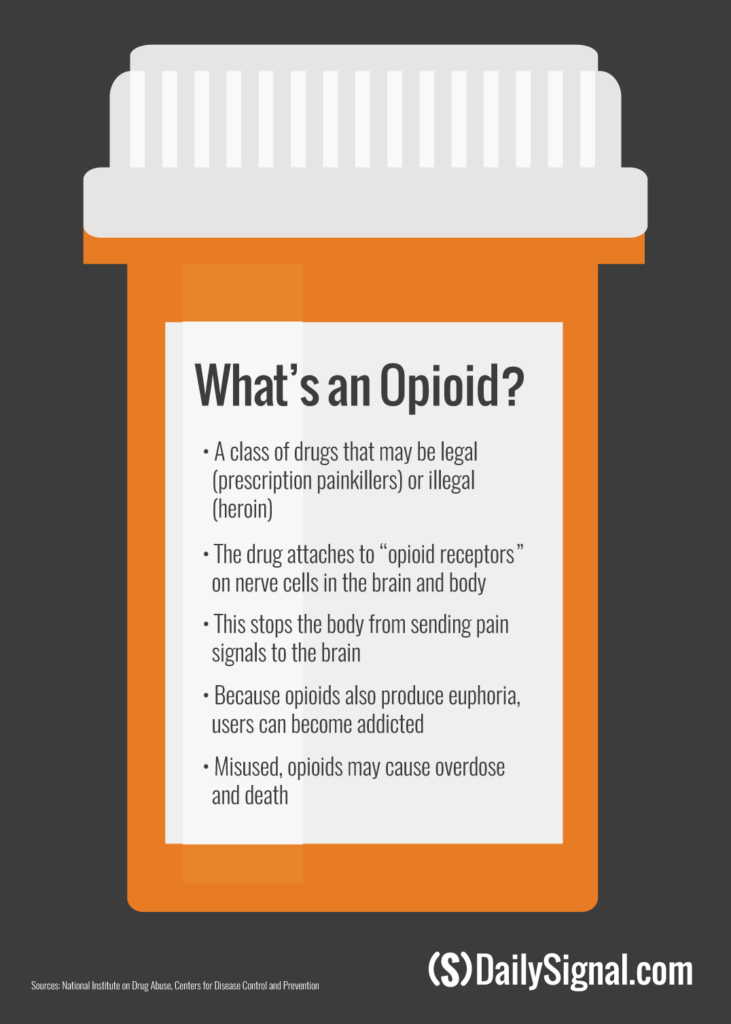

“I don’t judge these kids because I understand addiction and understand what dopamine does to your brain,” Latham says, describing how opioids target the brain’s reward system by releasing dopamine, a chemical that regulates feelings of pleasure.

Part 4 of 5: Police Assault on Opioids Gets Boost From a Family Doctor

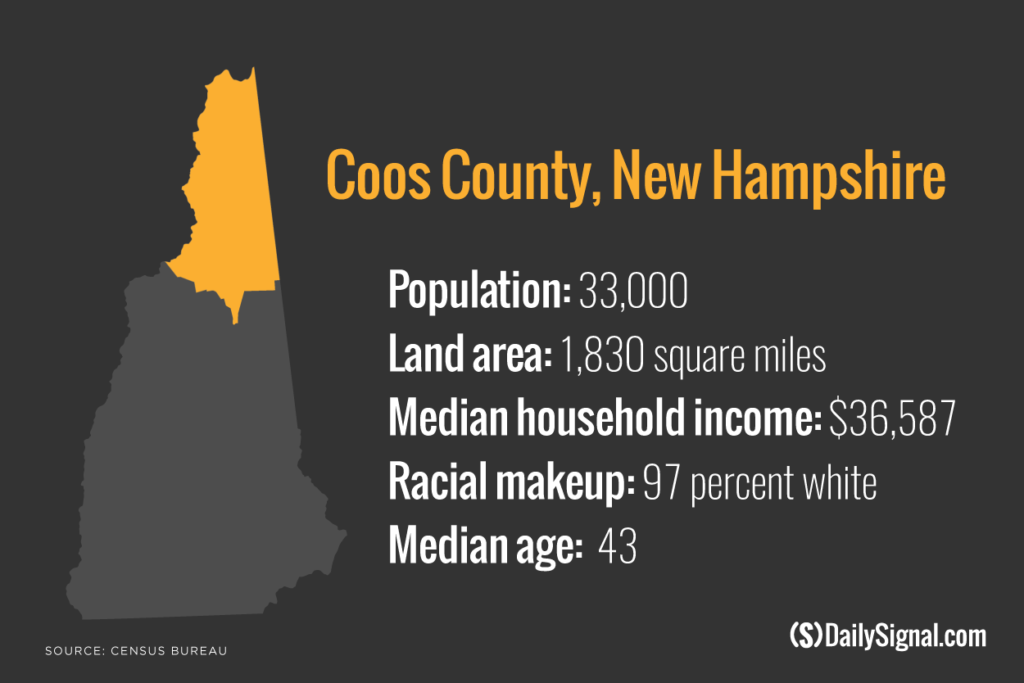

Latham, 63, is also ruthlessly committed to stamping out the illegal use—and spread of—opiates as they decimate Coos County, which has the highest combined death rate due to drugs, alcohol, or suicide in all of New England.

On a recent April afternoon, Latham, a measured, religious man with heavy bags under his eyes, is downright gleeful as he unveils a wad of note cards, bound with a rubber band. Embellishing, the physician says these cards contain the identities of “every opioid drug dealer within 100 miles of Colebrook.”

For the past 10 years, Latham has reported to law enforcement anybody he comes into contact with or knows about who he suspects to have sold or otherwise illicitly misused drugs, including prescription painkillers.

Some of these people are his patients, he says, and others are individuals who patients notified him about.

“The cards are kind of like a monument to say maybe we are doing something—maybe we are stopping some of this,” Latham says, slapping the stack of note cards against his lap to reflect the urgency of this region’s opioid addiction epidemic. “I am a good Mormon kid. I just don’t like to see people who have problems taken advantage of.”

Latham’s dual role—prescribing pain medicine and helping to secure punishment for those who he suspects don’t use it properly—is unusual in Coos County, the poorest, most northern, and least populated of New Hampshire’s 10 counties.

His position is also informal, although Latham doesn’t hide his cooperation with law enforcement.

Latham’s office, which looks like a house and is decorated as a private residence, with framed images of Jesus hanging from the walls, is located down the road from the Colebrook Police Department—the agency he principally works with.

Patients who receive prescription pain medicine from Latham must sign an agreement that plainly authorizes the doctor to “cooperate” with law enforcement and waives the normally sacred right of confidentiality for patients.

Latham says he will stop serving a patient if he suspects he or she is not handling medication responsibly—by using a higher dose than prescribed, selling the drugs, or diverting them to family and friends.

“My patients sign a drug agreement,” says Latham, who notes that about 20 of his 2,000 patients are on chronic pain medication. “If you sell, I turn you into the police. I can’t have one person destroy the program.”

Latham says patients who are misusing drugs, or know of others who do, are eager to share information because he isn’t a law enforcement official.

“The kids know what is happening,” Latham says, adding:

They will give me a name and tell me how much the heroin is going for. They just volunteer it. A lot of these kids have been in trouble with the law. It’s almost like they think, ‘I can’t go to the police with this because I had a problem one time.’ But they can trust me. This marriage between law enforcement [and] physicians has never been made. I am the only one doing this up here.

‘Need to Do Something’

While Latham’s actions may seem out of place, local law enforcement officials here—burdened by limited resources—welcome any form of help they can get.

Colebrook Police Chief Steve Cass jokes that this town, and others around it, are so small that he “pretty much knows everybody,” and if he doesn’t, “then I know somebody who does.”

Cass, 43, memorizes phone numbers—as he demonstrates to a reporter who tests him—and can recite most residents’ first and last names just by looking at them.

“I am a nut like that,” says Cass, who was born in Coos and intends to remain here because he loves living in a rural area where he can “step out on the back porch in my drawers and shoot my shotgun off.”

Colebrook Police Chief Steve Cass sometimes does patrols to supplement his nine-officer force. (Photo: Josh Siegel/The Daily Signal)

The chief says his agency is the only full-time police department in the area. Many of Coos County’s towns are unincorporated, and don’t have police departments.

The Coos County Sheriff’s Office, meanwhile, doesn’t handle criminal cases and focuses on civil services such as transporting inmates to various correctional facilities and providing security in state and federal courts.

Cass says he uses information provided by Latham just like any other tip he might receive, as a supplement to tactics the police department uses to combat drug crime, including enlisting confidential informants and doing undercover drug buys.

“I am willing to listen to anybody who wants to provide information,” Cass tells The Daily Signal in an interview, adding:

I’ve been around here long enough to know if someone wants to talk to me, I am going to listen. While Bruce [Latham] definitely has a finger on the pulse of the region, what he tells me is like anything you hear on the street about someone who is dealing pills or a narcotic. I have to make a case. I can’t just take what you say and go and do a search warrant. The information in itself doesn’t mean you can take down somebody.

Cass says Latham isn’t employed by, nor does he have any formal relationship with, the police department. The partnership has limits—the department does not share information with Latham about active investigations.

Latham says he first offered assistance to the police department about 10 years ago in response to a rash of opioid overdose deaths. Latham, who is originally from New Jersey, had just moved to northern New Hampshire to respond to a need for physicians.

“I remember the chief saying, ‘You see the smile on my face? You are the first doctor ever to walk into my office and be willing to help us.’ I said, ‘Chief, we have a major problem in this town. Every year we are losing 10 kids from drug overdoses. We need to do something. We have to work as a team on this.’”

In the view of Cass and Latham, if they could reduce illegal sources of drugs from the streets, there would be fewer drugs for people to become addicted to—and potentially die from.

“You don’t know all the things you prevented, but if you save one life it’s worth it to me,” Cass says.

‘Very Bad Information’

But still, some in the medical community question whether it’s proper—or effective—for a physician to take an aggressive approach in working with police.

Before Latham started his own practice in Colebrook in 2007, he was employed by the Indian Stream Health Center, the largest medical provider in Coos County.

This series:

Part 1: The Crisis That May Have Swung Voters From Obama to Trump

Part 2: One Opioid Addict Helps Another Choose Life Over Death

Part 3: ‘Dr. Father Pill’ Wants to Be Part of the Solution

Part 4: Police Assault on Opioids Gets Boost From a Family Doctor

Part 5: The First Responders Who Witness a Dreadful Toll

John Fothergill, a physician there who is also a state representative, hired Latham. He spent about a year at Indian Stream, the county’s leading prescriber of pain medication.

Fothergill says patients often report to him potential misuse of opioids he prescribed to others, but he treats these claims skeptically.

“The problem we have at the health center is the information we get from the public is very bad information in general,” Fothergill tells The Daily Signal in an interview. “Frequently, if person A won’t sell drugs to person B, person B may call the health center and say person A is selling drugs—just because he’s mad at him.”

Fothergill, 62, says opioid users who become addicts learn to lie to feed their addiction, and physicians aren’t in a position to determine the truth.

“I have had patients in the past say one thing, and then they have a come-to-Jesus moment and say, ‘I was lying,’” Fothergill says. “I don’t take much of it to heart—or at least I don’t take much of it to the police. A lot of these people certainly have problems. They are addicted to drugs, and to expect them to behave like honest citizens is somewhat unrealistic.”

Indian Stream works with law enforcement only in limited circumstances, Fothergill says, in situations where medical staff suspects easier-to-prove illegal activity, such as when a patient tampers with a urine sample during a drug test in order to be prescribed more medication.

“We certainly have a relationship with law enforcement,” Fothergill says. “They talk to us. We talk to them.”

Fothergill argues that it is wrong for medical providers to apply their own zero-tolerance policy to opioids misuse, because addiction—which can drive illegal activity—is best addressed through treatment.

Indian Stream requires patients who receive prescription pain medicine for 28 days or longer to participate in a substance abuse class or group therapy.

“People have to fail multiple times before we say we are really not helping you, you need to go some place else,” Fothergill says. “In our program, we expect them to be honest, but we try to provide increased help instead of just throwing them out.”

‘Sticky Thing’

John McCormick, Coos County’s attorney and chief law enforcement officer, appreciates the challenges in approaching a drug epidemic fueled by both legal and illegal behavior.

McCormick, who has a soft voice and cerebral demeanor, is contemplative as he discusses the circumstances in which he believes drug-related crime should be met with punishment rather than second chances.

John McCormick, Coos County attorney, says drug overdose deaths in the county decreased last year. But he says work remains to beat the opioid addiction crisis. (Photo: Josh Siegel/The Daily Signal)

Reflecting on the nuances of his job, he reveals to a reporter the number of drug overdose deaths in Coos reported to him in recent years—12 in 2015, nine in 2016, a few likely already this year, although it’s too early to know for sure.

“To beat this, I think it’s got to be sort of a multipronged approach,” McCormick tells The Daily Signal, sitting on a broken desk chair in his undecorated office. He adds:

I can tell you that some folks I have seen through the criminal justice system, I almost want to say they are almost in a better place in jail than outside of jail. I have seen addiction cases where if you let this person free, they are going to die. It’s that bad.

The county attorney, who has been in his position for nearly five years, adds that he has seen defendants die of a drug overdose before they go to trial for a drug-related case.

“We are not here to just throw everyone in jail,” McCormick says. “I don’t think we can just prosecute our way out of this. Treatment is worth a try. If they are not ready to receive that help or are not accepting it, the other alternative is jail.”

At the federal level, Attorney General Jeff Sessions has signaled a tougher approach to drug crime, recently ordering federal prosecutors to charge suspects with the most serious offense they can prove. But, McCormick says, it’s important to see each case for its unique characteristics.

McCormick says he usually reserves the most severe charges for suspects selling large quantities of drugs and for out-of-towners who travel to Coos County to sell drugs—usually from the Boston area—to take advantage of the demand. Repeat offenders also deserve stronger punishment, he says:

It’s kind of a sticky thing. I am aware of the addiction aspect, of course. I think I differentiate between someone who sells to use, and someone who sells just to profit; however, those lines are blurred. Every defense attorney will say their client is dealing to use.

McCormick, who knows Latham but doesn’t work directly with the doctor, says it’s challenging even for law enforcement to confirm the intent behind suspected illegal activity related to drugs.

“In these kind of cases, credibility is king,” McCormick says. “Sometimes you have to take what folks say with a grain of salt. Certainly, if they are serious addicts, we want to make them rehabilitate. At the same time, sometimes they know how to tell a good lie and manipulate folks in order to keep using. It’s a tough thing. We aren’t human lie detectors. It’s hard to sometimes tell whether someone is genuine.”

‘There Is Hope’

Seeking the proper balance between punishment and treatment, McCormick, Cass, and Latham all sound hopeful about a potential solution.

Coos County, working with the state, is in the process of creating a drug court.

In such a specialty court for offenders with substance abuse problems, defendants are able to access treatment services as an alternative to incarceration.

As the defendant receives treatment, he or she checks in periodically with the court, which closely monitors progress and can impose sanctions if the offender commits a new crime.

In August, McCormick is planning to travel to Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, a small, rural community, to observe how it runs its drug court.

With state funding committed, McCormick says he expects a drug court to come online in Coos County within a year.

He is careful not to portray a drug court as a panacea to the opioid crisis, however:

The idea is you get a little more supervision and oversight. I am cautiously optimistic it may have an impact and help at least some of the folks who are dependent on substances to steer away from illegal activity. I don’t want to say it’s not a solution. I don’t know if it will be a solution. But it can’t hurt.

Latham, the physician, says a drug court could achieve the difficult balance of providing an opportunity for people to better themselves, while also imposing consequences for those who continue to violate the law.

“My son was a heroin addict and has pretty much turned his life around,” Latham says of his only son, Chris, who was 15 when he started using drugs and is now in his 30s, married, and the father of a daughter.

“I am proud of the boy,” Latham says. “So I would say there is hope. It’s like that saying, you can’t change the spots on a leopard. I don’t treat leopards. I treat human beings, and they can change.”

Next, in Part 5 of 5: The first responders who witness the dreadful toll of opioid addiction.