As President Donald Trump settles back in Washington after his trip to Europe and the Middle East, his administration will continue to roll out related defense and foreign policy initiatives through multiple departments and agencies.

For the purposes of strategic planning, what organizing principle might be useful to inform such initiatives, consistent with existing statements of presidential intent?

Here is one such principle: Conceive and implement strategies of pressure against U.S. competitors overseas.

Consider the bigger picture. As Ted Bromund, Michael Auslin, and I suggest in a new American Affairs article, international circumstances have changed considerably over the last 10 to 15 years.

The “end of history” has now ended. The post-Cold War era is definitely over.

For a quarter-century, we’ve had various administrations from both parties that all operated on fairly optimistic assumptions about the trajectory of international relations.

The Clinton administration hoped that democratic enlargement could be pursued on the cheap.

The George W. Bush administration hoped that a Middle East freedom agenda, including regime change, would promote democracy and undermine terrorism.

The Obama administration hoped that diplomatic accommodations and U.S. military retrenchment would permit the arc of history to move forward in a benign direction.

All three projects were sincere. All three declared traditional power politics to be increasingly outdated.

But in the meantime, classical patterns of geopolitics, strategic competition, and international violence have not disappeared. Nor have America’s adversaries overseas.

On the contrary, many of them have been able to adapt, survive—even expand.

An Increasingly Hostile World

We continue to live in a competitive international arena, not just economically, but strategically. So we need to prepare for some steady, long-term competition.

Under these circumstances, there is certainly a temptation to disengage. Yet an underlying U.S. forward presence abroad remains wise.

This need not require fresh interventions in every single case. Indeed, in recent years the popular and political mood within the United States has sometimes been remarkably gloomy about the benefits of international engagement.

But the U.S. remains by far the world’s most powerful country, with an unmatched range of capabilities if its leaders choose to use them effectively.

America’s alliance system, in particular, is a striking asset, unmatched by any other power. If these alliances didn’t exist, given ongoing challenges, we’d probably have to reinvent them at considerable expense. Why throw them away?

Part of the long-term confusion has flown from a rather gauzy definition of what threatens the United States. It’s become fashionable over the years to refer to various disembodied global trends as U.S. national security challenges, whether or not they actually are.

But for a strategy to be of any use, it should refer directly to groups of human beings with hostile intent, whether at the level of national governments or non-state actors.

Failed states, for example, are not automatically a threat to the U.S. unless their collapse interacts with, or encourages, some significant political forces hostile to America.

The Threats We Face

In terms of threats to U.S. interests, the current challengers come in three main varieties.

First, there are major power competitors, namely Russia and China. Second, there are rogue state adversaries, such as North Korea and Iran. Third, there are jihadist terrorists, including ISIS and al-Qaeda. Not coincidentally, all three varieties of actor are authoritarian.

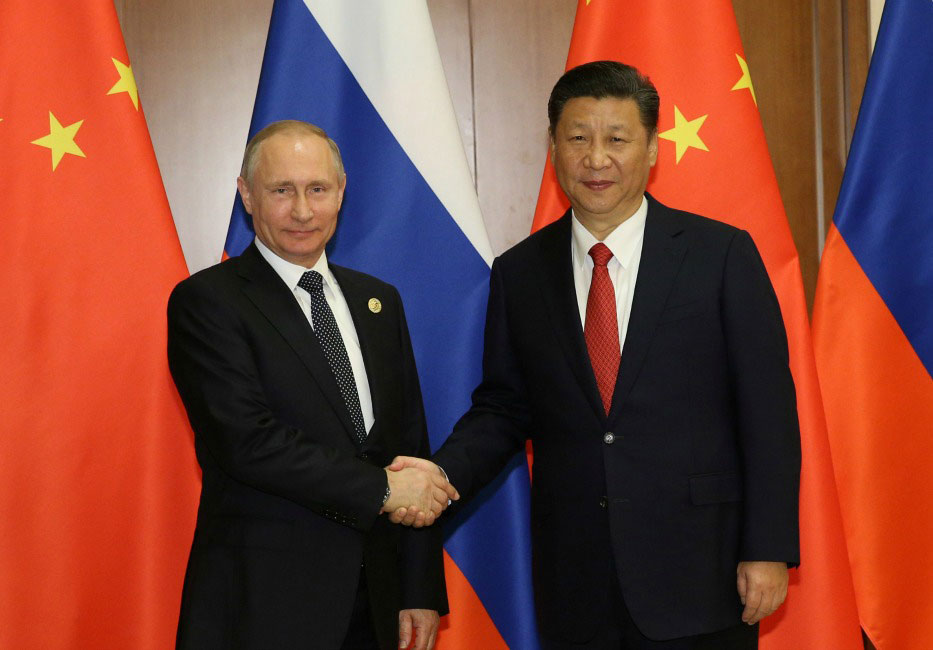

President Donald Trump has sought to strategically cooperate with both Russian President Vladimir Putin, left, and Chinese President Xi Jinping, right, despite core differences in national interests. (Photo: Pool/Reuters/Newscom)

For the most part, what we seek with major power autocracies such as Russia and China is robust peaceful competition. This will require a certain conceptual and material shift from previous years.

There is of course room for diplomacy and cooperation, case by case, alongside such competition. We need not mistake competitors for bitter enemies. But we should also not mistake our great power competitors for friends.

In relation to these major competitors—and even in relation to rogue state adversaries—there is usually no need for an openly declared policy of direct rollback or regime change.

Instead, the U.S. should look to impose costs, gain leverage, and intensify pressure against both types of states, in regionally differentiated ways. It should look to revive the art of deterrence, precisely to avoid open warfare.

There’s also a need to distinguish clearly between friends and enemies. This entails not spending too much time hectoring our allies on their own domestic practices. We should defend and support our international alliances, while simultaneously resisting our adversaries.

Being an ally of the United States has to mean something. Otherwise, we’ll end up with fewer allies. And diplomatically, we need to work from our alliances outward, rather than the other way around.

The U.S. should apply a wider variety of policy instruments to frustrate and pressure major power challengers, rogue state adversaries, and Islamist terrorists.

Such policy instruments include rebalanced alliance relationships; responsible foreign assistance; economic sanctions where appropriate; aggressive covert action; bilateral trade agreements; robust intelligence capabilities; canny diplomacy; military leverage; and bolstered U.S. defense spending.

And in relation to jihadist terrorist groups who seek the death of American civilians, the goal must be the terrorists’ destruction.

We certainly need to learn the right lessons from the 2003 invasion of Iraq, without learning the wrong ones. Our governments have never been especially good at predicting future wars.

So the right lesson is not to be complacent, much less to build down militarily, but to take any possible use of force deadly seriously. This means taking great care and forethought before intervention—and then, once decided upon, acting with overpowering force and capability.

Defending the Global Order

All things considered, the great challenge today is not to further liberalize or globalize an American-led order, but to simply defend that order, so that it better serves U.S. national interests.

Americans will always hope for the spread of democracy overseas, but for the most part our adversaries will not be quickly transformed, and the U.S. continues to face a number of determined competitors internationally. Let’s pay them the compliment of taking them seriously.

An effective U.S. foreign policy strategy will tap into America’s underlying strengths—which are in fact immense—to wear down and pressure numerous adversaries without wearing out the United States.

An extended version of this article originally appeared in The National Interest.