President Donald Trump’s revised executive order on immigration is back in court, and therefore back in the news.

On Monday, a three-judge panel of the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals heard arguments on the order’s constitutionality. Opponents of the order claim that it violates the Establishment Clause by setting up a ban on Muslim immigration.

This argument seems strange, since the order does not purport to do any such thing, and in fact applies only to a handful of predominantly Muslim countries for only a short period of time.

Some lower courts, however, have held the order unconstitutional—not because of what it says and does, but because of things Trump said on the campaign trail last year.

In essence, these courts have gone beyond the words of the order itself and claim to have found an impermissible, anti-Muslim intention behind it in the mind of the president.

In taking this interpretive path, the judges in question have followed an example set by the Supreme Court in some recent Establishment Clause cases.

But as I explain at greater length in an issue brief for The Heritage Foundation, there is an older, more venerable, safer tradition that counsels against judges making such an inquiry.

>>> What 2 Obama Judges Got Wrong in Striking Down Travel Executive Order

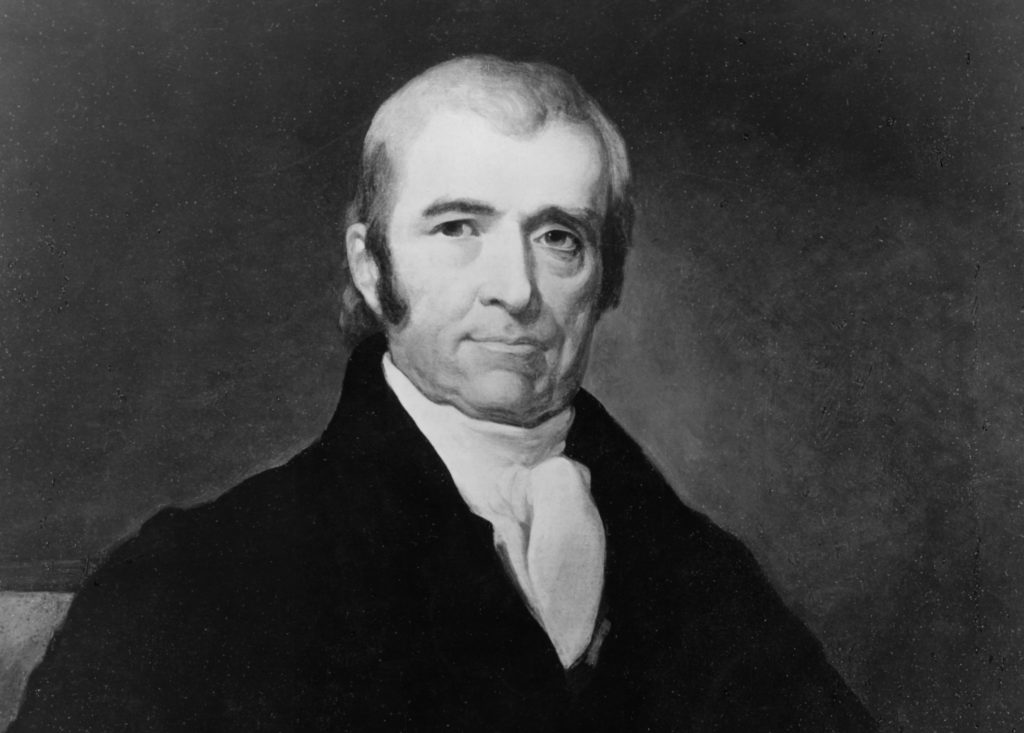

Under the leadership of John Marshall, “the great chief justice,” the early Supreme Court declined to look beyond the words of the law to the personal intentions of its authors.

In Fletcher v. Peck (1810), the court refused to say that a state law providing for the sale of public lands could be held invalid because of the corrupt motives of the legislators.

After all, Marshall pointed out, it would be difficult, if not impossible, for a court to say how far such corruption had to extend in order to justify an invalidation of the law.

John Marshall (1755-1835) was the fourth and longest-serving chief justice on the U.S. Supreme Court and played a foundational role in developing the U.S. legal system. (Photo: akg-images akg images/Newscom)

In Sturges v. Crowninshield (1819), the court declined an invitation to interpret the Contracts Clause—not on the basis of its rather expansive wording, but instead on the narrower immediate intentions of those who wrote it.

While Marshall conceded that “the spirit of an instrument” must be “respected not less than its letter,” he also admonished that “the spirit is to be collected chiefly from its words.”

We might ask why modern courts should follow Marshall in declining to look into the personal intentions of the lawmaker. The answer is that preservation of the rule of law requires such judicial modesty.

Rule of law does not mean rule by judges acting on their whims. Rather, it means that cases will be determined on the basis of objective information examined through accepted modes of reasoning.

>>> Why Trump’s Revised Executive Order Is Constitutional, Legal, and Common Sense

As Marshall suggested in Fletcher v. Peck, however, an inquiry into the subjective motives of the lawmaker quickly leads judges into a realm in which there are no clear, compelling standards of judgment.

This problem arises not only in dealing with a multiplicity of intentions, such as those that move a legislative body to action. We also confront it when dealing with a legal pronouncement—like the president’s executive order—which proceeds from one person.

After all, even the actions of a single individual are usually complex, motivated by more than one intention. It is certainly possible that in signing the executive order, Trump intended to deliver in some limited, indirect way on the “Muslim ban” about which he mused during the campaign.

But it is equally, if not more possible, that Trump also intended to make the country more safe by regulating immigration from a set of nations known to have problems with terrorism.

There can be no objective, compelling reason for a court to lay hold of the president’s impermissible motive while discounting the permissible motive.

The court can only be exerting its raw will to seize upon the impermissible motive in order to achieve a desired outcome—namely, invalidating the order.

In Federalist 78, however, Alexander Hamilton promised the nation that courts would only exercise “judgment” and not “will.”

We should therefore hope that the 9th Circuit follows the path of judicial modesty marked out by Marshall and judge the executive order by its words—and not the endlessly debatable intentions that may lie behind it.