In an early test of his foreign policy, President Donald Trump is facing a decision on whether to contribute thousands of additional U.S. troops to America’s longest-running—and often overlooked—war.

As first reported by The Washington Post, Trump’s senior military and foreign policy advisers recommend that the president send 3,000 to 5,000 more troops to bolster an existing U.S. force of 8,400 in Afghanistan and help that country’s government gain momentum in a 15-year war against the Taliban, the Islamist insurgent group.

Experts who study the Afghanistan War say the plan is designed to break a stalemate in the fighting, and to pressure the resurgent Taliban to negotiate a peace agreement with the Afghan government.

These experts, in interviews with The Daily Signal, say the proposed strategy does not represent a dramatic U.S. escalation to a war in which America once committed 100,000 troops.

But they say if Trump were to approve the plan—he’s expected to make a decision before a May 25 NATO meeting in Brussels—it would challenge the president’s evolving foreign policy doctrine. That doctrine has trended toward a narrow counterterrorism-first approach rather than deep commitments to overseas conflicts.

“My best guess is [Trump’s advisers] are looking to at least stop the bleeding in Afghanistan at the moment,” Bill Roggio, who edits the Foundation for Defense of Democracies’ Long War Journal, said in an interview with The Daily Signal. “They are also doing what they think they can get away with and what is politically acceptable. There is not a lot of support in the American public, and among members of Congress, for a significantly deeper U.S. commitment to the Afghanistan War.”

Roggio said he did not think the additional troops would fundamentally change the situation in Afghanistan, where more than 2,000 U.S. troops have died and another 20,000 have been wounded.

“The Taliban have had momentum for several years now,” Roggio said. “They have weathered a full surge of U.S. forces. The Afghan security forces have not been able to hold the gains. So I don’t think an incremental increase in troops will affect the situation all that much.”

‘Rise From the Dead’

Yet Roggio and others say an extra U.S. presence could reverse declines in the security situation in Afghanistan.

President Barack Obama, who had pledged to end U.S. military involvement in Afghanistan, steadily reduced the American role, but did not completely pull out troops due to a number of security challenges.

The Taliban is gaining territory. Reuters reports the Islamist group controls 40 percent of the country, and that casualties for government forces reached record levels last year. In addition, the terrorist group al-Qaeda has established new footholds in Afghanistan, the country it used to plan the 9/11 attacks. And ISIS also has established a small presence in Afghanistan.

“Afghanistan is not the only place, and even the most important place at any given time [for U.S. interests],” Michael O’Hanlon, director of the foreign policy program at the Brookings Institution, said in an interview with The Daily Signal. “But as we have seen with the Taliban surge, and ISIS gaining a foothold there, it’s pretty clear this area has an ability to allow bad guys to rise from the dead. You want a sustained presence in Southeast Asia as the easternmost pillar in the counterterrorism capacity of the United States.”

‘Not a Surge’

Currently, American forces in Afghanistan have two primary missions: advising and training Afghan forces and conducting counterterrorism missions, including a recent raid that killed the leader of ISIS’ affiliate there, Abdul Hasib.

According to The New York Times, the new Trump administration plan would allow American advisers to assist a larger number of Afghan forces, and work closer to the front lines. Under the proposal, the U.S. would also not set a firm deadline for withdrawing troops, as Obama did.

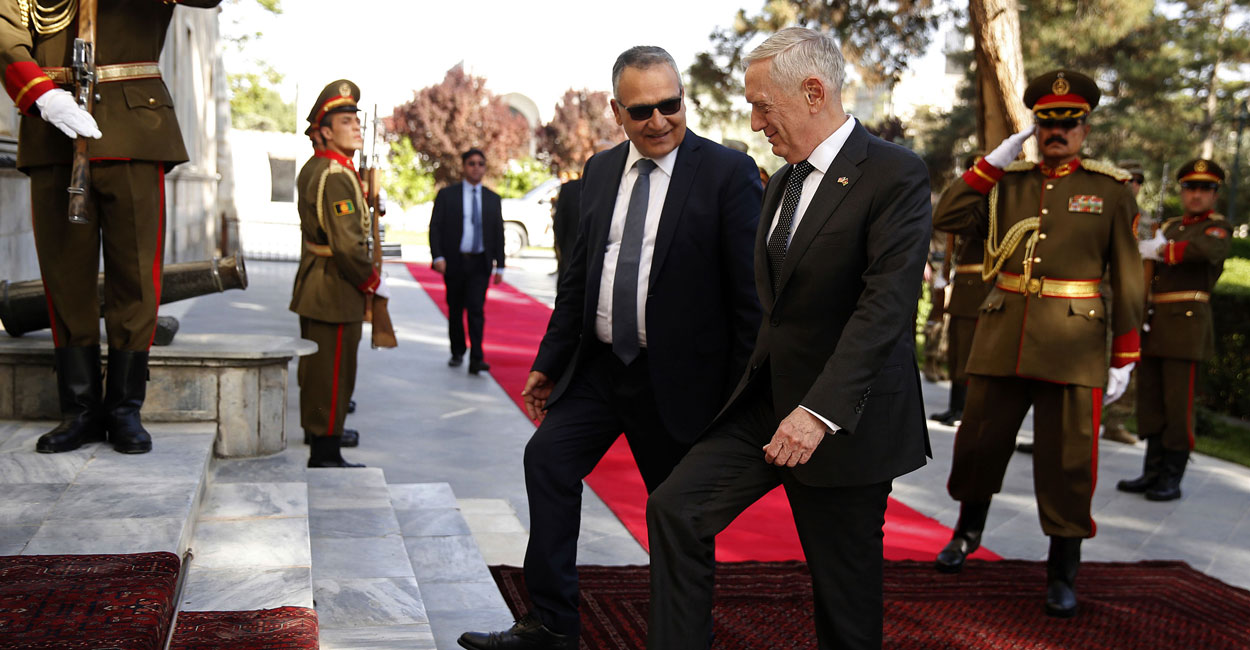

Defense Secretary James Mattis, center right, is greeted by presidential palace staff as he arrives to meet with Afghanistan’s President Ashraf Ghani in April. (Photo: Jonathan Ernst/Pool/Zuma Press/Newscom)

“This is not a surge,” said James Jay Carafano, vice president for foreign and defense policy at The Heritage Foundation, who advised Trump’s transition team. “This is still going to be an Afghan-led thing.”

Carafano, a retired Army officer, added:

It’s not a dramatic expansion of the conflict where we go in there and say we will win once and for all. It’s about how we get to conditions on the ground that keep Afghanistan on a path to stability. That’s what’s driving the troop numbers.

Others say the Trump administration risks being stuck in a middle-ground position, with little realistic chance for new peace talks unless both sides make concessions.

The challenges for peace are exacerbated at a time when Afghanistan’s security leadership faces allegations of corruption, and the Taliban has shown little inclination to make concessions.

The Taliban also has been buffered by support from Iran and Russia, while Afghanistan’s neighbor, Pakistan, continues to provide a safe haven for militant groups.

Testifying before Congress in February, Army Gen. John W. Nicholson Jr., the top American commander in Afghanistan, called for a “holistic review” of policy toward and financial aid for Pakistan.

“It’s always been a close call on its merits, on whether it’s worth waging war in Afghanistan or not,” Stephen Biddle, a senior fellow for defense policy at the Council on Foreign Relations, said in an interview with The Daily Signal, adding:

You can still make a reasonable case for it and against it. I don’t think this is a hopeless situation. It’s not crazy to suppose we can get a compromise settlement. But that requires we get serious about this, which includes the Trump administration owning this process and expending political capital to build a constituency to support it.

Guarding Against ‘Catastrophic Events’

Rebecca Zimmerman, a policy researcher at RAND Corporation who focuses on Afghanistan, sought to downplay expectations for what an enhanced U.S. presence in the country could do.

She says U.S. support is most needed to prevent collapse of the Afghan government, which would make the country an ungoverned space to be exploited by extremist groups.

“The biggest threat to the U.S. is government collapse in Afghanistan,” Zimmerman told The Daily Signal. “If that happens, there is a likelihood of a multiparty civil war, and the countryside will be open to anyone who wants to plant a terrorist flag there. If we can support the Afghan forces to guard against catastrophic events that can fell the government, we would be using those troops effectively.”

With no near-term endgame, Roggio of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies says it’s fair to question whether the U.S. should continue to supply troops and funding — about $23 billion annually — to the Afghanistan War.

But he says walking away from Afghanistan would present immeasurable costs.

“It’s never wrong to question why we are still at war 15 years later,” Roggio said. “We should be asking hard questions about why we are sending service members to die. But it would be massive victory for jihadist groups across the world if the U.S. decided to pull out of Afghanistan.”