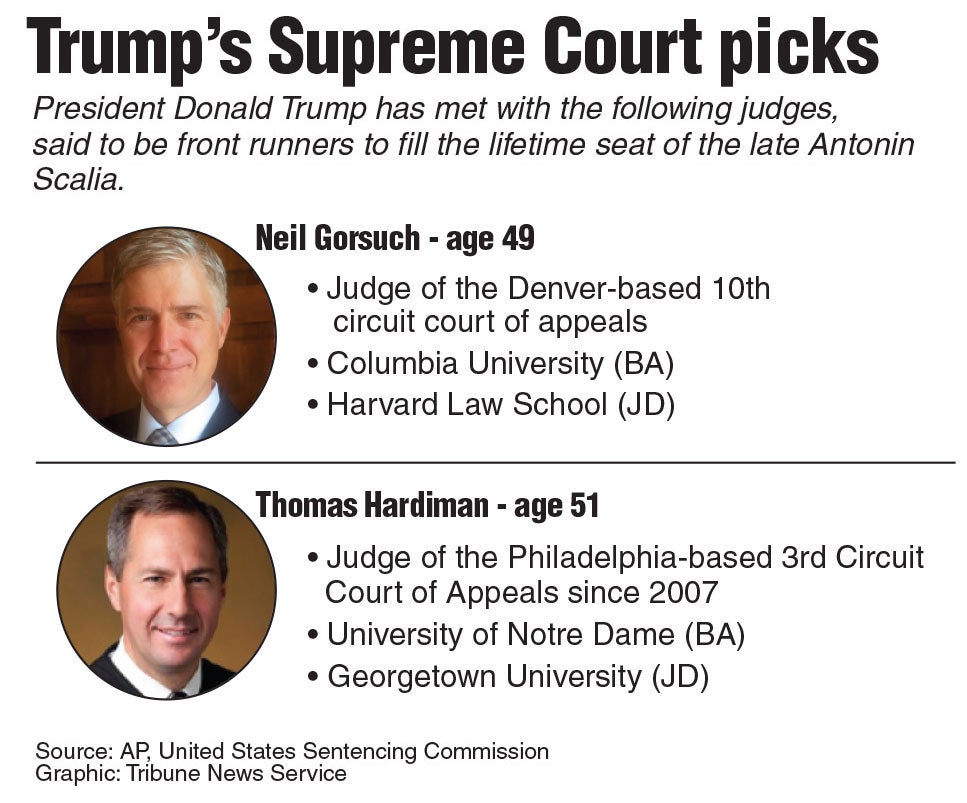

President Donald Trump returns to prime time Tuesday for the biggest announcement of his presidency so far. He will reveal at 8 p.m. EST his pick for the Supreme Court, widely reported to be one of two federal appeals court judges—Neil Gorsuch or Thomas Hardiman.

Some reports suggest two other appeals court judges, William Pryor and Diane Sykes, still could be in contention.

However, neither of those judges won unanimous confirmation to their current posts. The Senate confirmed Gorsuch by a voice vote in July 2006 and confirmed Hardiman 95-0 in March 2007.

Unanimous confirmation for past judgeships, however, isn’t likely to prevent Senate Minority Leader Charles Schumer, D-N.Y., from trying to block the nominee, said Carrie Severino, chief counsel for the Judicial Crisis Network.

“It will be hard to say the nominee is out of the mainstream if Schumer has already voted for him,” Severino told The Daily Signal. “But Trump could renominate Merrick Garland and the Democrats would reflexively block it.”

Some Democrats already have threatened to filibuster Trump’s nominee, whoever he or she is.

President Barack Obama nominated Garland, chief judge of the Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, to fill the vacancy left after the Feb. 13 death of Justice Antonin Scalia. Senate Republicans refused to advance the nomination in an election year.

It’s not likely Trump will have a high court nominee approved by April, when the Supreme Court probably will hear its last set of cases for the year, said Curt Levey, president of the Committee for Justice.

“With [Supreme Court Justices] Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, it took about three months,” Levey told The Daily Signal. “I supported stopping the Garland nomination, but the one thing Republicans can’t do is hurry this, or act as if filling the vacancy is urgent. I don’t think the Democrats can filibuster, but they will have to play to their base’s anger over Garland.”

Gorsuch ultimately has a more in-depth history of writing with regard to constitutional rights, separation of powers, and the role of judges, said John Malcolm, director of the Edwin Meese III Center for Legal and Judicial Studies at The Heritage Foundation.

“It will be hard to say the nominee is out of the mainstream if Schumer has already voted for him,” @JCNSeverino says.

But, Malcolm added, Hardiman has a more compelling personal story: He financed law school by driving a taxi, wrote impressive decisions on the Second Amendment, and represented religious freedom cases pro bono while in private practice.

“It will still be a fight, but not be as much of a knock-down, drag-out fight as if [Trump] had chosen Bill Pryor,” Malcolm told The Daily Signal. “Both would be superb Supreme Court justices, and I hope either gets confirmed.”

Here’s a look at the record of Trump’s potential nominees:

Backgrounds

Gorsuch, 49, was appointed by President George W. Bush as a judge on the Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit in Colorado.

Before that, Gorsuch was a deputy assistant attorney general at the Justice Department. The Harvard Law School graduate clerked for both current Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy and former Justice Byron White.

Bush appointed Hardiman to the Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit in Pennsylvania. That’s the same court that Trump’s sister, Judge Maryanne Trump Barry, serves on.

Hardiman, 51, previously was a federal district judge for the Western District of Pennsylvania, a position confirmed by a voice vote of the Senate in October 2003. He received his law degree at Georgetown University.

On Gun Ownership

A Judicial Crisis Network brief noted Gorsuch’s decision in the case of United States v. Games-Perez, where the appeals judge wrote that “there is a long tradition of widespread gun ownership by private individuals in this country.” He added: “The Supreme Court has held the Second Amendment protects an individual’s right to own firearms and may not be infringed lightly.”

For his part, Hardiman rejected a challenge to a law barring felons from owning firearms.

But Hardiman generally has been strong on the Second Amendment.

In the case of Drake v. Filko, Hardiman wrote the dissenting opinion in a ruling upholding a New Jersey law requiring residents have a “justifiable need” to obtain a permit to carry a gun. Citing Supreme Court decisions upholding the Second Amendment, he wrote: “States may not seek to reduce the danger by curtailing the right itself.”

On Religious Freedom

Gorsuch ruled in two major religious liberty cases that came before the 10th Circuit challenging the Obamacare mandate that employers pay for birth control and abortion-inducing drugs for employees, siding with Hobby Lobby and the Little Sisters of the Poor in the two cases.

In a lower-profile case, Yellowbear v. Lampert, Gorsuch ruled in favor of an inmate who said prison officials denied his religious freedom by not accommodating his Native American faith.

In one case, Hardiman wrote the dissenting opinion in favor of a mother and her kindergartener son, who was prohibited from using the Bible as part of a show and tell at school. He wrote that the prohibition “plainly constituted” discrimination based on the family’s viewpoint.

On Free Speech

Gorsuch issued a decision against a Colorado campaign finance law, determining that it unconstitutionally permitted major party donors to make two contributions per election cycle, while limiting minor party candidates to receive just one donation per election cycle. There is “something distinct, different, and more problematic afoot,” he wrote, “when the government selectively infringes on a fundamental right.”

Hardiman ruled against a student’s right to wear a bracelet that said “I [heart] boobies” during a breast cancer awareness campaign at his middle school. He described the case as “close,” but said it “would seem to fall into a gray area between speech that is plainly lewd and merely indecorous.”

In the case of NAACP v. City of Philadelphia, Hardiman ruled that Philadelphia’s ban on noncommercial advertisements at the city’s airport violated free speech rights.

Concerning campaign finance, Hardiman wrote the opinion striking down a Philadelphia law that barred police officers from contributing to the police union’s political action committee.