Media and advocacy groups have claimed that President-elect Donald Trump’s nomination of Sen. Jeff Sessions, R-Ala., to be our next U.S. attorney general has killed criminal justice reform. But those naysayers have forgotten their history and the nature of federalism.

In 2001, it was not a Democrat but Sessions who introduced measured sentencing legislation to drastically reduce the sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine offenses. In 2010, his leadership paved the way for passage of the Fair Sentencing Act.

Of all the media and advocacy groups sounding the death knell for federal criminal justice reform, perhaps none has been as enthusiastic as New York magazine. It published an editorial titled “Sessions as Attorney General Means Criminal Justice Reform Is Dead.”

Why? “For manifold reasons of background and ideology … Jeff Sessions as attorney general is a nightmare come to life for people who care about the enforcement of civil rights and voting rights” and in “an especially destructive way: criminal justice reform.”

This is wrong for at least three reasons:

First, states and localities are responsible and accountable for most of the work in criminal justice matters. More than two dozen states already have enacted criminal justice reform packages; others are considering doing so.

We have cause for optimism for some much-needed federal reforms, such as addressing overcriminalization with a review of the oversized and often duplicative federal criminal code, and adopting “mens rea” reform to ensure that inadvertent violations of obscure criminal laws do not indelibly mark morally innocent citizens as criminals.

Second, conservative leaders in the House and Senate, such as House Judiciary Chairman Bob Goodlatte, R-Va., have championed “responsible, commonsense reforms”—including overcriminalization and mens rea proposals—“to ensure our criminal justice system reflects core American values.”

Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, says he has seen “increasing bipartisan sensitivity to overcriminalization issues and an increasing openness on the part of members of Congress to re-evaluate federal criminal laws and regulations with an eye toward making some commonsense incremental changes.”

Third, New York magazine and others have mischaracterized Sessions’ record and outright ignore his work on criminal sentencing. Although today that topic is often thought of as a liberal one, it was Sessions who over a decade ago perceived an injustice and acted.

Through the 1980s and ’90s, “tough on crime” fervor fueled many political decisions in federal criminal legislation in ways that, in hindsight, seem to have been overzealous at times.

One of those decisions was to enact certain mandatory minimum sentences for illegal drug offenses in the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. The act established “a five-year mandatory minimum sentence for trafficking 500 grams of powder cocaine or 5 grams of crack and a 10-year mandatory minimum for trafficking 5,000 grams of powder or 50 grams of crack.”

This sentencing ratio came to be referred to as the 100-to-1 disparity.

As Heritage Foundation legal scholar Paul J. Larkin Jr. wrote in the Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy, the Congressional Black Caucus favored these stiff mandatory minimum sentences at the time, seeing the destruction that crack cocaine had wrought in black, inner-city neighborhoods. In time, some who initially had supported this law came to see it as racially discriminatory.

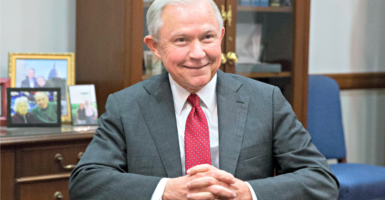

Enter Jeff Sessions.

Conservative columnist Quin Hillyer recalls Sessions in the late ’90s speaking about addicts and criminals “not with vilification, but with compassion.” Hillyer describes Sessions over the next decade as “tough on crime, but he seemed troubled to the core by the thought of sentencing injustice, especially with a racial component.”

In December 2001, before it became a politically popular idea, Sessions introduced the Drug Sentencing Reform Act to increase punishment for powder cocaine and reduce punishment for crack offenses to a 20-to-1 ratio.

The bill also proposed to shift focus in sentencing “from drug quantity to criminal conduct,” “increasing penalties for the worst drug offenders,” and decreasing penalties on unwitting or low-level and nonviolent parties “who play only a minimal role in a trafficking offense,” such as children or a significant other.

Sessions said at the time that the disparity in sentencing between crack cocaine and powder cocaine “is not justifiable” and “these changes will make the criminal justice system more effective and fair.”

It took almost a decade for others to catch up. But as the Supreme Court noted in Dorsey v. United States (2012), Congress finally passed legislation, the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, in part “because the public had come to understand sentences embodying the 100-to-1 ratio as reflecting” sentencing disparities that were, as Sessions said, “unjustified.”

The Fair Sentencing Act, co-sponsored by Sessions and Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., reduced the 100-to-1 disparity to 18-to-1.

The latter ratio, as The Washington Post reported in 2010, reflects “data that crack has a slightly more powerful and immediate addictive effect and more quickly devastates the user physically than does powder cocaine,” and also is associated with “higher levels of violent crime.”

Media and advocacy groups seem to have forgotten that.

Last year, the United States Sentencing Commission released a five-year impact analysis on the law. The commission found that the Fair Sentencing Act “reduced the disparity between crack and powder cocaine sentences, reduced the federal prison population, and appears to have resulted in fewer federal prosecutions for crack cocaine.”

This wasn’t simply ignoring drug offenses, however, as the commission found that all this occurred “while crack cocaine use continued to decline.”

Media and advocacy groups haven’t mentioned that.

Sessions was ahead of many of his colleagues by nine years in the effort to “bring measured and balanced improvements in the current sentencing system to ensure a more just outcome.”

Media and advocacy groups don’t give Sessions credit for that.

Sessions, like the president-elect who picked him for attorney general, may well be ahead of criminal justice naysayers today.

With regard to his nomination, Sessions said: “I enthusiastically embrace President-elect Trump’s vision for ‘one America,’ and his commitment to equal justice under law. I look forward to fulfilling my duties with an unwavering dedication to fairness and impartiality.”

With overcriminalization of some behavior and the erosion of mens rea in federal criminal law, the nation has reason to focus on unfairness in the criminal justice system.

As Ed Feulner, former president of The Heritage Foundation, recently wrote, “you could be breaking a federal law and not even know it. And the fact that you didn’t know you were doing so, or didn’t intend to break the law, would make no difference.”

Media and advocacy groups don’t seem concerned about the risks that average people face.

The public has no reason to assume that, as attorney general, Sessions would be anything but fair and impartial in considering those issues. His record shows that, even when much of the public was not behind him.