While the debate over illegal immigration tends to focus on how to control and treat those who make it across our nation’s borders, a more enduring challenge for the U.S. government has been what to do to stop legal entrants from overstaying their allotted time here.

The problem of so-called visa “overstays”—which make up about 40 percent of the 11 million people living illegally in the U.S.—will continue on past the Obama administration and follow the next president.

That’s partially because the government has not yet delivered on its long-promised—and congressionally mandated—plan to create a better checkout system to track who has left the country on time, and who hasn’t.

“It [visa overstays] is the most overlooked issue when it comes to immigration,” Rep. Michael McCaul, R-Texas, who chairs the House Homeland Security Committee, said in an interview with The Daily Signal.

“It’s an untold threat,” McCaul added. “We are allowing millions of people to overstay visas and remain in this country who could potentially pose a threat to homeland security.”

The uncertainty around the scope of the problem comes at a time when a growing percentage of the illegal immigrant population is made up of visa overstays as opposed to people being apprehended at the border.

For more than 20 years, the U.S. government had struggled to quantify just how many people entered the country legally with a visa and stayed too long, making it impossible to prescribe policy fixes.

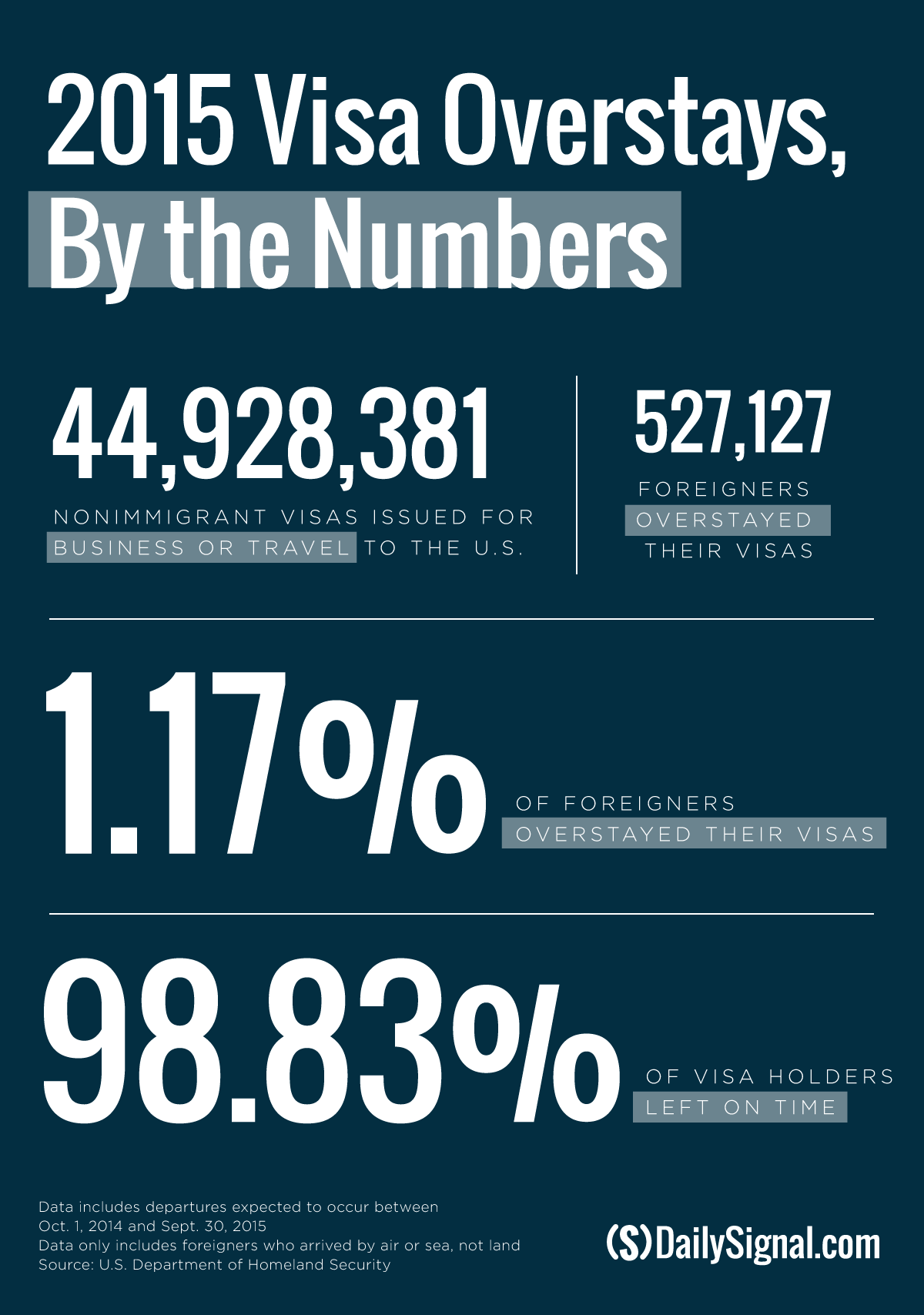

That finally changed in January, when the Department of Homeland Security released a first-of-its-kind study reporting that 527,127 people who traveled legally to the U.S. for business or leisure and were supposed to leave the country in fiscal year 2015 in fact overstayed their visas.

>>> Nearly 500,000 Foreigners Overstayed Their Visas Last Year. What That Means.

This figure is larger than the 337,117 people caught crossing the border illegally last year.

The long-awaited data from 2015 was not all-encompassing. It counted only visa holders who entered the U.S. by air and sea, not by land, and it did not include those who came as students or temporary workers.

Still, immigration and security experts as well as policymakers welcomed the new information because they thought it would force the government to move faster on methods to improve, most importantly in trying to assemble a system to obtain biometric data—such as fingerprints, facial recognition images, and eye scans—on those leaving the country.

‘A Top Issue’

The 9/11 Commission recommended the Department of Homeland Security complete an entry and exit system “as soon as possible,” viewing it as an important national security tool because two of the hijackers on Sept. 11, 2001, had overstayed their visas.

Plagued by financial and logistical challenges, the government has introduced various pilot projects at some airports and land borders, but is still a few years off from implementing a biometric exit system on a large scale.

Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson has pledged to have biometric checks at major airports in 2018, and Congress in last year’s omnibus spending bill authorized $1 billion in visa fee increases over 10 years to pay for an exit system.

The struggle to install a biometric exit tracking system is well known.

Foreigners who apply to enter the U.S. on a visa are interviewed and photographed and have their fingerprints taken at a consulate overseas before arriving here. But collecting biometric data on those exiting the country is not as easy.

That’s because U.S. airports do not have exclusive terminals for domestic and international flights, which makes it hard for officers from Homeland Security’s Customs and Border Patrol to screen overseas travelers and get their information.

“Most countries have a designated checkout system built in airports,” Stewart Verdery, a senior Homeland Security official during George W. Bush’s administration, said in an interview with The Daily Signal. Verdery added:

We just didn’t build our airports this way. So the question is where do you collect the information in a way that doesn’t inconvenience travelers and is actually effective in making sure someone has left? None of the options are particularly great. And though the biometric equipment is very mature, there is also a manpower issue over who maintains the machines.

To satisfy these limitations, Verdery expects the government to pursue a facial recognition exit system that automatically would snap a traveler’s photograph—likely at the gate.

‘It Doesn’t Matter’

Even if the U.S. were to settle on a workable exit tracking method, some national security experts doubt that such a system would be an effective counterterrorism tool, especially when considering its cost.

David Inserra, a homeland security expert at The Heritage Foundation, says the government could just as well use already collected biographical information, such as a traveler’s name and date of birth, to track exits and collect overstay data. But other experts say bad actors could use fake passports and aliases to bypass a system that did not require biometrics such as fingerprints and facial recognition.

No matter the method used, Inserra and other experts note that an exit system simply reveals who has departed—and remained—in the country. It would not help discover where those that stayed are living, and whether they present a security risk.

“Even if you have the greatest biometric exit system, if someone doesn’t leave, it doesn’t matter,” Inserra said, adding:

You are now left with the problem of every other police officer looking for someone. They are a missing person who doesn’t want to be found. If you want to stop visa overstays, the solution isn’t to spend money on an exit system.

Inserra argues that policymakers instead should give more money to intelligence agencies such as Homeland Security’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement so they can go into communities and try to locate—and deport—people who overstayed their visas.

Rep. Michael McCaul, R-Texas, says visa overstays are an “untold threat” that deserve more attention. (Photo: Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call/Newscom)

Yet other experts are doubtful that would happen. They say the government does not prioritize enforcing immigration law against those who’ve stayed past their visa expiration date because those travelers were screened before coming here.

“In terms of removing a garden variety illegal migrant, you aren’t going to search for somebody on that basis,” Edward Alden, an immigration and visa policy expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, said in an interview with The Daily Signal. “The notion we will have some special dedicated effort to go find overstays I find completely implausible.”

Alden says the government can take simpler steps to deter visa overstays, by emailing reminders to foreigners of their expected departure date, specifying the consequences of not leaving on time.

Many who overstay their visas don’t intend to settle in America, Alden contends.

The Homeland Security report from earlier this year found that as of Jan. 4, a total of 416,500 of the 527,127 overstays in 2015 remained in the U.S. More have left the country since then, the government says.

The government also has taken diplomatic steps to better track foreign visitors, especially by improving information sharing with Canada, the country that had the most overstays in the U.S.

The U.S. and Canada exchange names and biographical information of those from third countries who enter on their shared border. Mexico, the second-largest source of visa overstays in the U.S., generally does not yet have the capacity to exchange information like that, Alden says.

‘Serious About Enforcement’

Despite these improvements, Congress is not backing off its demand for a biometric exit system.

McCaul, the chairman of the House Homeland Security Committee, says he hopes for a vote next year on a broad border security bill he sponsored last year. It includes a provision requiring the government to establish an exit system at the 15 largest airports, seaports, and land ports within two years.

The legislation, which President Barack Obama promised to veto, would impose financial and other penalties on Department of Homeland Security political appointees if the government fails to meet the timeline.

Having the best data possible, supporters of the exit system say, will give the government incentive to more aggressively enforce the law against those who’ve overstayed visas.

“I think once the government gets an exit system up and running, they’ll be serious about enforcement,” Verdery said, adding:

We will never have a system where we will go out and find someone who overstays and just wants to do nothing on their buddy’s couch. But we will go out and find them when they try to get a job, draw the attention of law enforcement, or illegally try to claim benefits.