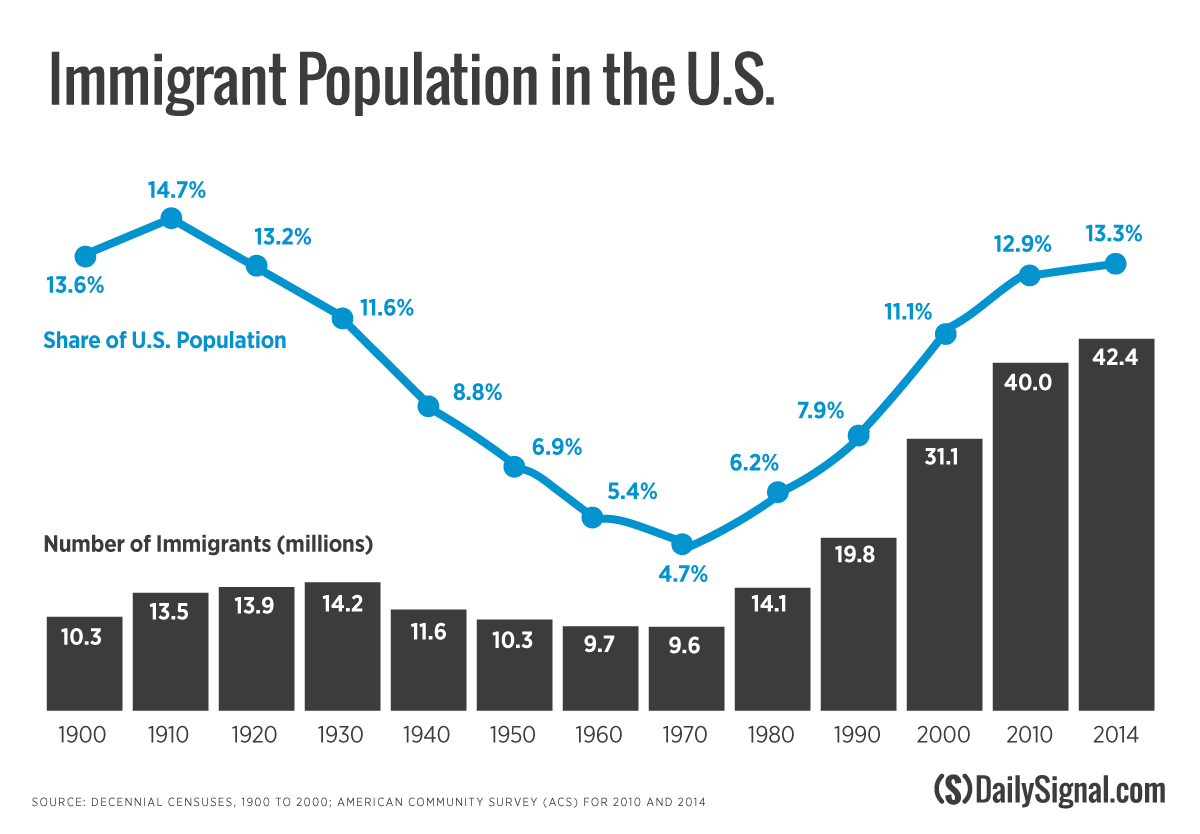

There are more immigrants living in the United States than ever before. The foreign-born are more likely to come from China and India—often equipped with skills and a higher education—than Mexico.

Many of the immigrants who live here have called the U.S. home for a while—an average of nearly 21 years—and their economic and social progress improves over time.

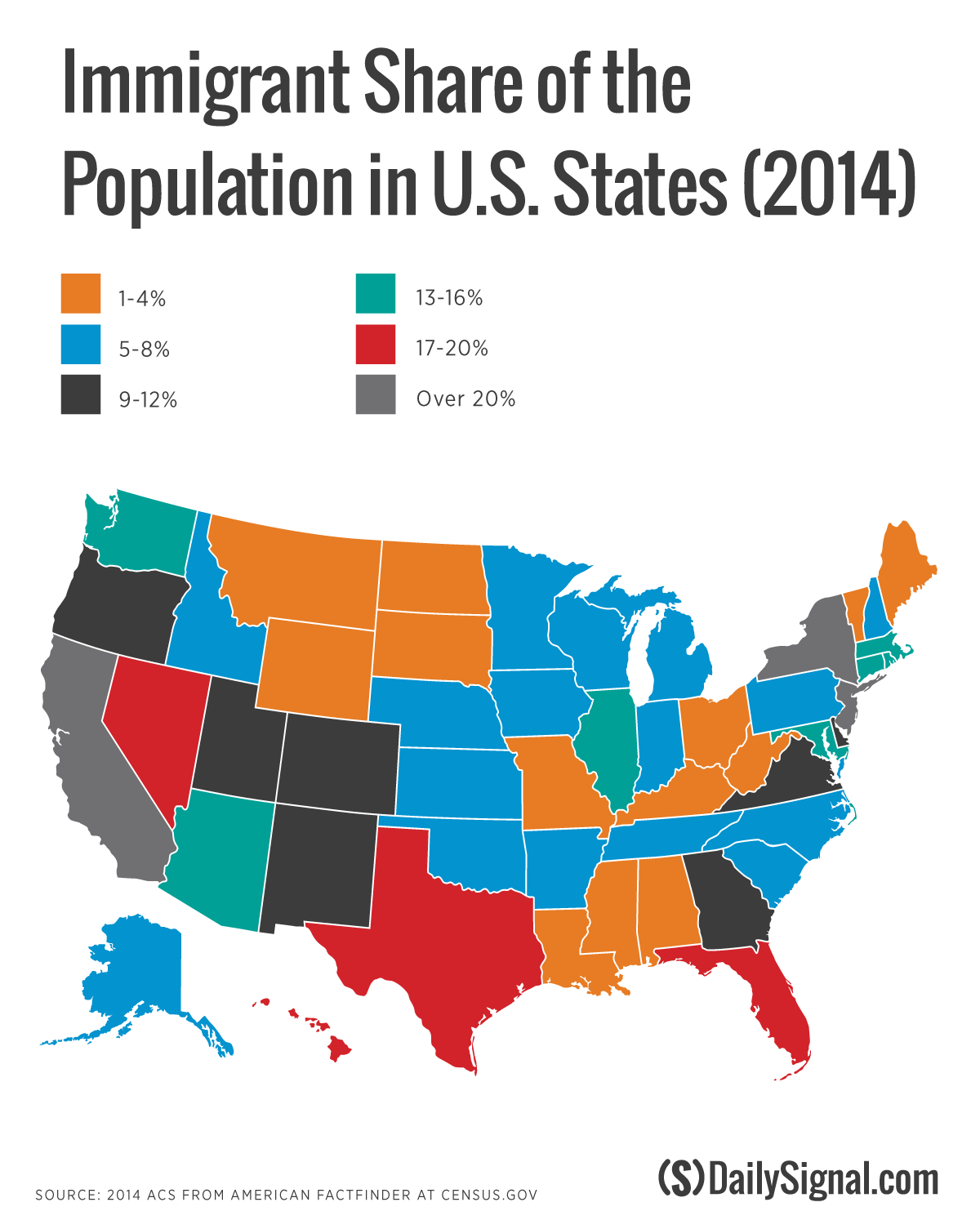

Immigrants continue to flock to places where there are others like them. California has nearly one-fourth of the nation’s immigrants living there, while New York and Texas remain popular places for non-natives to call home.

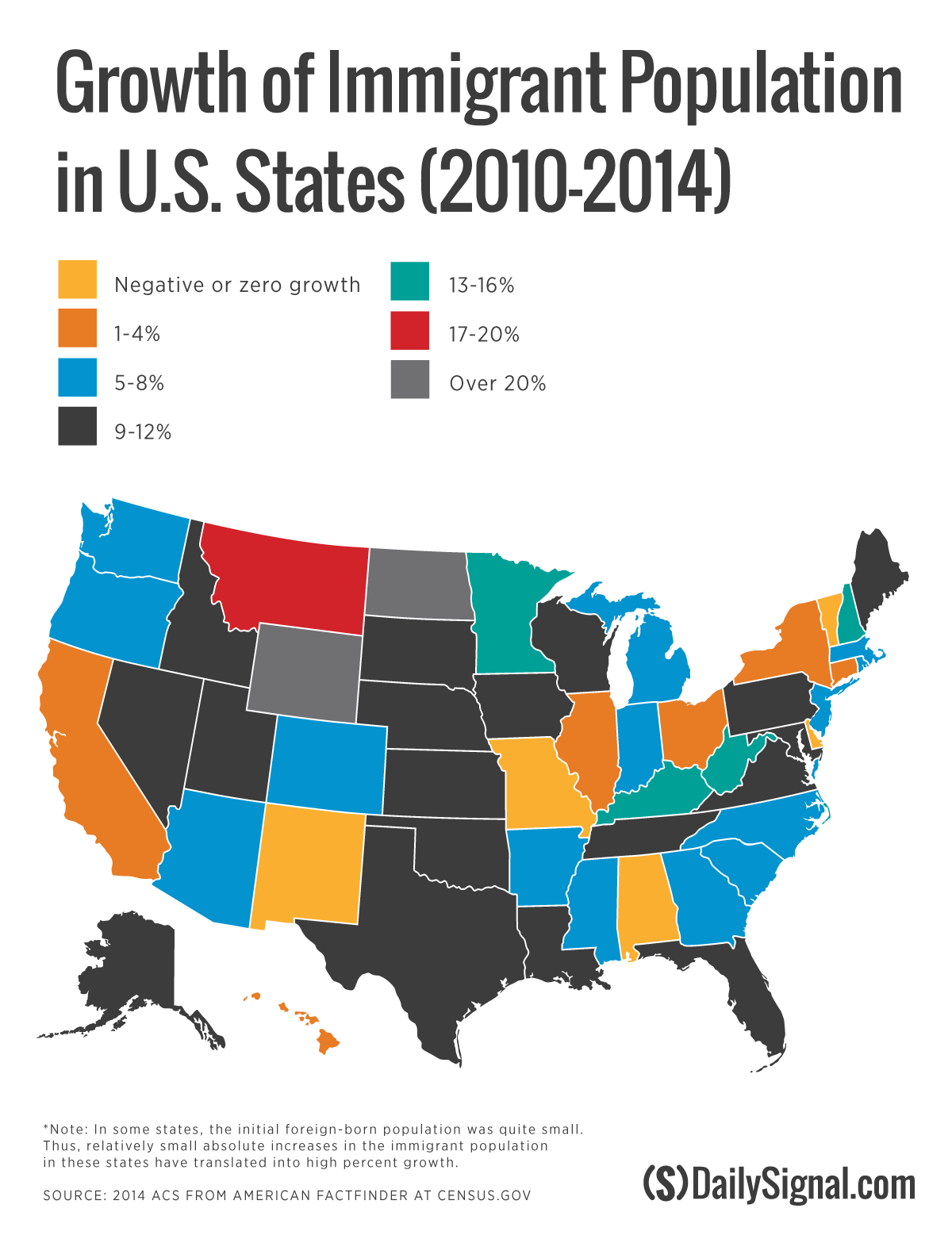

But states outside of traditional immigrant settlements—like Georgia, North Carolina, Minnesota, Colorado, Washington, and Nevada—have also seen significant increases in their foreign-born populations.

This is the profile of the nearly 43 million immigrants residing in the U.S. today, as told from 2014 and 2015 Census Bureau data presented by the Center for Immigration Studies in a recent report.

The study, which includes figures for both legal and illegal immigrants, comes at a time when the question of what to do about immigration is a defining political issue. It’s a debate that promises to continue into a future where the foreign-born occupy a larger and larger percentage of many states’ populations, and the makeup of the nation’s immigrants is proving to reflect the rich-poor divide in America, from wealthy technology innovators, to poor agricultural workers.

“We are kind of heading into uncharted territory when it comes to immigration,” said Steven A. Camarota, the author of the report who is the director of research for the Center for Immigration Studies, which advocates for less immigration.

“From a policy perspective, I would expect efforts to further increase the level of immigrants to the U.S. of all kinds, including family-based and skill-based. I think you will see constituencies trying to satisfy sectors as varied as the hotel and restaurant industries, Silicon Valley, and ethnic advocacy groups that are more about family immigration,” Camarota told The Daily Signal in an interview.

The portrait of U.S. immigrants presented in the study will likely be interpreted depending on how an individual values immigration.

Just take education, a measurable where the picture of immigrants is nuanced.

In 2014, 30 percent of immigrants lacked a high school diploma or General Educational Development (GED) certificate, compared to 10 percent of their native-born counterparts.

Yet, that same year, 29 percent of the 36.7 million immigrants ages 25 and older had a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 30 percent of native-born adults.

Interestingly, the share of college-educated immigrants is higher—44 percent—among those who entered the country since 2010. That trend is not an accident, experts say.

India was the leading country of origin for new immigrants in 2014, with 147,500 arriving to the U.S. out of 1.3 million total foreign-born individuals who moved to America that year.

About 40 percent of Indian immigrants hold a graduate degree. Fewer than 12 percent of native-born Americans do.

China had the second-largest amount of new entrants to the U.S., with 131,800. And though Mexico ranked third on this list in 2014—130,000 came from there that year—the net number of Mexican immigrants living in the U.S. has not increased since 2010, and even illegal immigration by Mexicans has decreased drastically since the recession.

Illegal immigration is increasingly coming from Central America, where women and children fleeing violence and poverty in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras seek asylum in the U.S.

“Since the recession, the number of Mexican immigrants coming to the U.S. has not grown—that’s an under-told story in the data here,” said Randy Capps, the director of research for U.S. programs at the Migration Policy Institute, which is nonpartisan.

“Contrast that with the rapid growth in the number of Chinese and Indian immigrants—which in total is still a quarter of the number of U.S. residents from Mexico. The numbers of Chinese and Indians are the biggest source of growth now and going forward. People who come from those two countries have increasingly strong economic ties to the U.S., have strong middle-class backgrounds with the ability to get more education as needed, and have more resources and relatives already in the U.S. That’s the future of immigration in America.”

Despite these positive trends, Camarota is quick to point to other indicators that he argues show costs to immigration.

Once they come here, immigrants are more likely to not have health insurance coverage than the native-born. In 2014, 27 percent of the foreign-born were uninsured, compared to 9 percent of natives.

Also that year, 27.1 percent of immigrants and their U.S.-born children under 18 were on Medicaid, compared to 17.9 percent of natives and their children.

More immigrants were in poverty in 2014 (18.5 percent of them), in contrast to 13.5 percent of natives.

While the foreign-born and natives make equal use of cash assistance programs, more immigrant households use food assistance programs.

Most concerning to Camarota, he says, is a downward trend in the number of native-born young adults without a college degree who are not working, a marker that he considers related to competition with immigrants for low-wage jobs.

In 2000, 66 percent of natives 18 to 29 years old with only a high school education were employed. That compares to 53 percent of such U.S.-born young people who were working in 2015.

“This is a point that we should be giving a lot of thought: the drastic deterioration in work among native-born young people,” Camarota said. “And if you don’t work when you are 18, the chance you will work at 27 is a whole lot less. This shows the argument that we have a shortage of workers and need to bring people to the U.S. to be nannies, maids, and busboys is absurd.”

Capps acknowledges Camarota’s concerns over less educated young people not working, but he argues there are many factors that contribute to that. He points to the data showing that gaps are closing between immigrants and natives in skills, education, and wages, and that the foreign-born improve on those indicators the longer they reside in the U.S.

All together, immigrants and natives have virtually identical rates of employment and labor force participation, according to the Center for Immigration Studies report.

“On the legal immigration side, it’s just the reality that we still have a very generous system, with 1 million coming to the U.S. every year,” Capps said. “It’s correct to note there are some costs to that. There are always costs associated to a group as big as 1 million people coming here, with job competition and public benefit use being some of them. But these are relatively small costs compared to the broader economic benefits of so many people immigrating here, many of them now coming with high skills.”