Russia’s invasion of eastern Ukraine and annexation of Crimea have left many wondering: Where next for Moscow?

While no one can read Russian President Vladimir Putin’s mind, we can examine historical precedent to construct feasible scenarios for future Russian action. Here, we’ll review six such scenarios, each reflecting three assumptions regarding how Putin sees Russia’s role in the world:

Assumption 1: The West today is dealing with an imperial Russia and not a Cold War Russia. Putin’s vision for Russia is closer to that of the czars than that of the rulers of the Soviet Union, meaning he is more interested in expanding Russian military, economic, and political influence than spreading an ideology.

Assumption 2: Putin is willing to use military force to protect “compatriots”—those loosely defined as ethnic Russians, Russian speakers, and other groups sharing cultural, religious, or historical ties to Russia but residing outside Russia’s contemporary borders.

Assumption 3: Given current geopolitical circumstances, it is unlikely (albeit not impossible) that Putin will risk a total war with the United States by invading a NATO member. Non-NATO options for intervention are available across Eastern Europe and Eurasia—options that would allow Putin to reveal the West as ineffectual and disunited without automatically triggering a full-scale war with the alliance.

So what are these non-NATO scenarios?

Some involve direct threats to U.S. national interests; others raise only indirect threats. However, all six share one common theme: Russia exerts influence beyond its present borders but still inside its old imperial frontiers.

1. ‘Protecting’ the Gagauzs in Moldova

Gagauzia, a tiny, autonomous region in Moldova, checks most of the boxes for Russian meddling. Though ethnically Turkic, Gagauzs are Orthodox Christian and Russian speaking. Gagauzia passed from the Ottoman Empire to the Russian Empire with the Treaty of Bucharest (1812).

Today, it is the poorest region of Moldova, and Gagauzs blame the westward orientation of the central government for many of their problems. Pro-Russian sympathies run deep in Gagauzia. In Moldova’s 2014 national elections, the pro-Russian Socialist Party got its best result in Gagauzia.

Last year Gagauzs elected a pro-Russia bashkan, or governor. While the rest of Moldova is targeted by Russian economic sanctions, Gagauzia enjoys an exemption.

In February 2014, as the crisis in Crimea peaked, 98.4 percent of the voters in Gagauzia expressed a preference for closer relations with the Russian-backed Eurasian Customs Union over the European Union.

Controlling Gagauzia would strengthen Russia’s position vis-à-vis Ukraine. An estimated 1,500 Russian troops are already in Transnistria, the breakaway region of Moldova, which shares a 250-mile border with western Ukraine.

Bringing Gagauzia under Russian influence would help to complete Putin’s control along Ukraine’s western border. It also would place Ukraine’s Odesa Oblast under further threat from Russian aggression. This is especially true for the Odessan region of Budjak, which along with Moldova forms the historical region of Bessarabia, once part of the Russian Empire.

The scenario aligns with Putin’s imperial vision of the region and his designs on Ukraine.

2. Stoking Separatism in Georgia’s Samtskhe-Javakheti Province

Putin views the Republic of Georgia as part of Russia’s natural sphere of influence and stands ready to “influence” the country by force if necessary.

In August 2008, Russia invaded Georgia, coming within 15 miles of the capital, Tbilisi. Today, an estimated 11,000 Russian troops occupy the regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia in violation of the 2008 cease-fire agreement.

Russia also appears to be exploiting ethnic tensions in the Armenian-populated Georgian province of Samtskhe-Javakheti. The goal may be to create a sphere of influence linking Russia with Armenia through South Ossetia and Samtskhe-Javakheti.

Armenian separatists in Samtskhe-Javakheti are not as vocal as they were a few years ago. But Moscow might easily re-energize separatist movements in the region—a job made easier by the poor availability of bilingual education (Armenian and Georgian) as well as new citizenship and immigration restrictions Tbilisi has placed on Javakheti Armenians. Many Javakheti Armenians work in Russia and have Russian sympathies, so these policies breed animosity that Moscow whips into a separatist frenzy.

An unstable Samtskhe-Javakheti would advance Russian strategy for Georgia and the broader South Caucasus region. Georgia’s territorial integrity would be further dismembered. Bringing the region under Moscow’s influence would make a land corridor by which Russia could supply its growing military presence in Armenia one step closer to being realized.

Major oil and gas pipelines pass through the region as well. At a time when Europe is trying to move away from Russian-supplied energy, the stability and operation of these pipelines is vital.

3. ‘Military Assistance’ for Southern Turkmenistan

Modern-day Turkmenistan was one of the last regions in Central Asia to succumb fully to Russian control during imperial times. It regained its independence in 1991 after the collapse of the Soviet Union, but remains one of the world’s most closed societies.

Turkmenistan leans toward isolationism and self-described “permanent neutrality” in foreign relations. Ashgabat, the capital, has refrained from joining Russian-backed alliances such as the Eurasian Economic Union and the Collective Security Treaty Organization. However, the security situation across the border in northern Afghanistan is challenging this.

As Taliban and other Central Asian militants were pushed from the Afghanistan-Pakistan border region, many found their way to northern Afghanistan. Since early 2015, an increasing number of security incidents involving Taliban militants and Turkmen border guards has resulted in the deaths of dozens of Turkmen conscripts.

Today, a myriad nefarious actors operate in Afghan provinces bordering Turkmenistan’s Lebap and Mary provinces. They include Pakistani Taliban, local Turkmen Taliban, local Turkmen militia units, remnants of the militant Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, and organized criminal groups. Turkmen authorities have responded by trying to seal the border with Afghanistan using fences, ditches, and various means of surveillance.

Moscow increasingly is concerned about the deteriorating security situation in northern Afghanistan and Turkmenistan’s seeming inability to contain the threat. In January, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov visited Ashgabat and offered Russian weaponry and training to help Turkmenistan secure the border. In June, Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu also visited Ashgabat to reiterate this offer.

Some experts believe the next offer will be “help” in the form of Russian troops to patrol the border. There is precedent: Until 2005, Russian troops patrolled Tajikistan’s border with Afghanistan. And Russian troops still patrol Armenia’s border with Turkey. They patrolled Turkmenistan’s border with Afghanistan in the early 1990s, after independence.

Once Russian troops deploy to Turkmenistan, they likely would remain for the foreseeable future, allowing Moscow to gain another strategic foothold in the region.

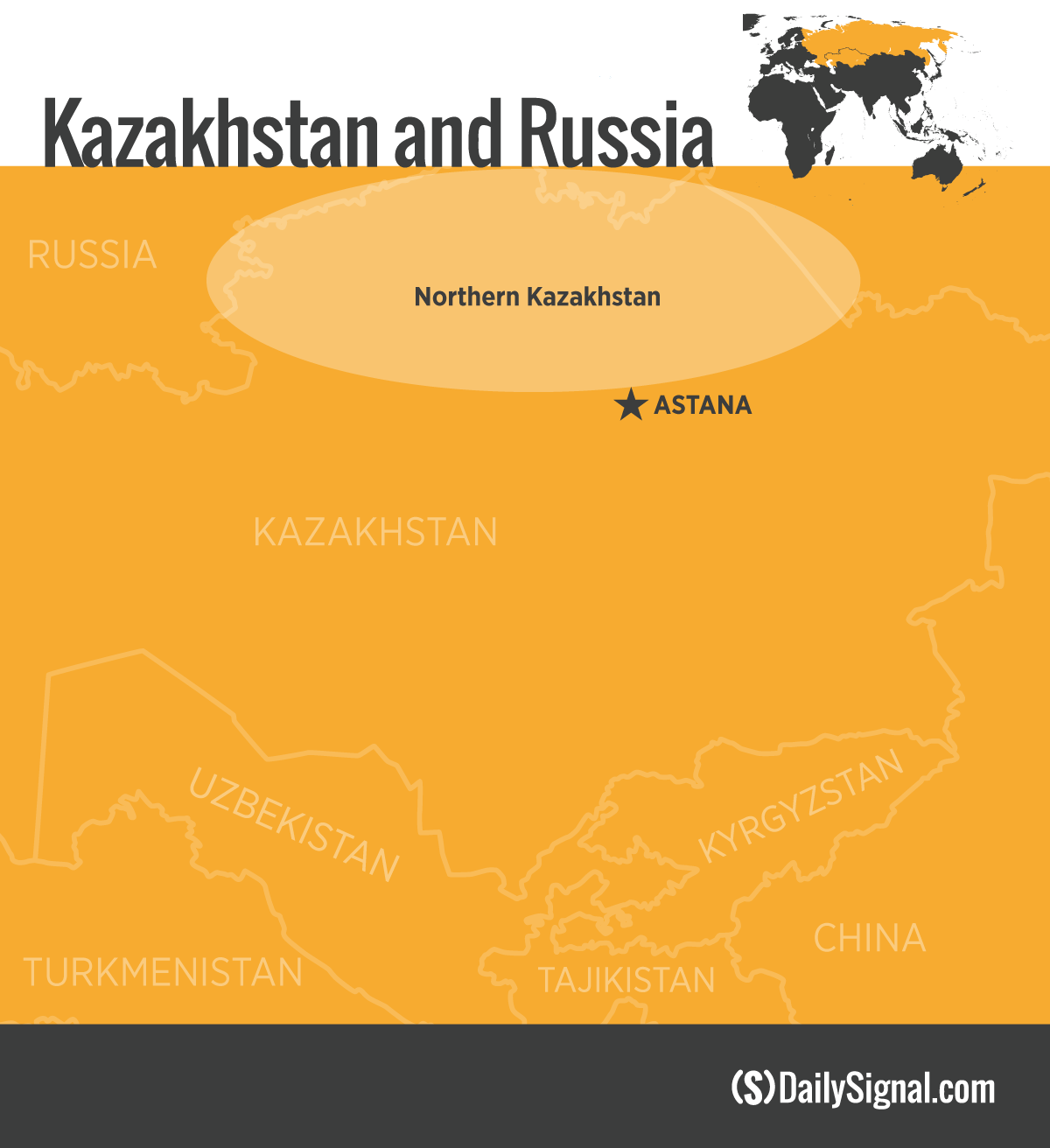

4. ‘Protecting’ Ethnic Russians in Northern Kazakhstan

Russia dominated Kazakhstan for almost 200 years. But since regaining its independence in 1991, Kazakhstan has developed its own regional policy that tries to be distinct from Russia.

Even so the capital, Astana, retains close ties with Moscow through membership in the Russian-backed Eurasian Economic Union and the Collective Security Treaty Organization.

One-fifth of Kazakhstan’s population is ethnic Russian. Most of these live along the country’s 4,250-mile border with Russia. After Russia annexed Crimea in early 2014, many ethnic Russians from Kazakhstan were said to sympathetic with their counterparts in eastern Ukraine, and some have fought alongside the separatists in the Donbas region.

Kazakhstan’s government has placed restrictions on Russian language teaching and advertising, and cracked down on pro-Russia social media postings. There is uncertainty about who will succeed President Nursultan Nazarbayev, now 76.

Added to this is an emotional attachment many Russian have to Kazakhstan for reasons of nostalgia.

During World War II—perhaps the most crucial time for the Soviet Union—Kazakhstan was instrumental in providing weapons to the front lines. Kazakhstan was also home to the Baikonur launch site used for space exploration and the Semipalatinsk nuclear testing site. It played a key role in Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s Virgin Lands Campaign in the 1950s and 1960s. All of this was important during the Cold War.

These factors could be used as a pretext for a Russian intervention.

Provocative comments by senior officials in Moscow have heightened this fear. In 2014, Putin suggested that “the Kazakhs had no statehood.”

Russian intervention in northern Kazakhstan would prove once again that Russia is willing to use its military strength to protect ethnic Russians, sending a message to others in the region.

5. ‘Peacekeeping Force’ for Azerbaijan’s Nagorno-Karabakh Region

Armenia and Azerbaijan clashed in 1988 when Armenia made territorial claims on Azerbaijan’s Karabakh Autonomous Oblast. The war left 30,000 dead and hundreds of thousands internally displaced.

The conflict has been “frozen” since 1994, when the warring parties signed a cease-fire agreement. Armenian forces and Armenian-backed militias continue to occupy almost 20 percent of the territory that world leaders recognize as part of Azerbaijan.

But since August 2014, violence has increased noticeably along the Line of Contact between Armenian and Azerbaijani forces. It reached a peak this past April.

The Minsk Group, tasked with bringing a lasting end to the war, remains the recognized mediating body but is de facto inoperative for now due to the breakdown in Western relations with Moscow over the issue of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The Ukraine conflict already gives Putin a useful excuse for keeping thousands of troops in Armenia.

Over the years there have been suggestions that Russia wants to deploy “peacekeepers” to the Nagorno-Karabakh region against the will of Azerbaijan. Basing Russian troops in Azerbaijan under the guise of peacekeeping would provide Moscow another strategic foothold in the South Caucasus.

Should that happen, Nagorno-Karabakh likely would never be returned to Azerbaijan, because it would be in Russia’s interests to keep a military presence there for as long as possible. Also, if Russia’s military presence in Armenia is anything to go by, a large Russian military presence in Azerbaijan would block Baku’s closer relations with the West.

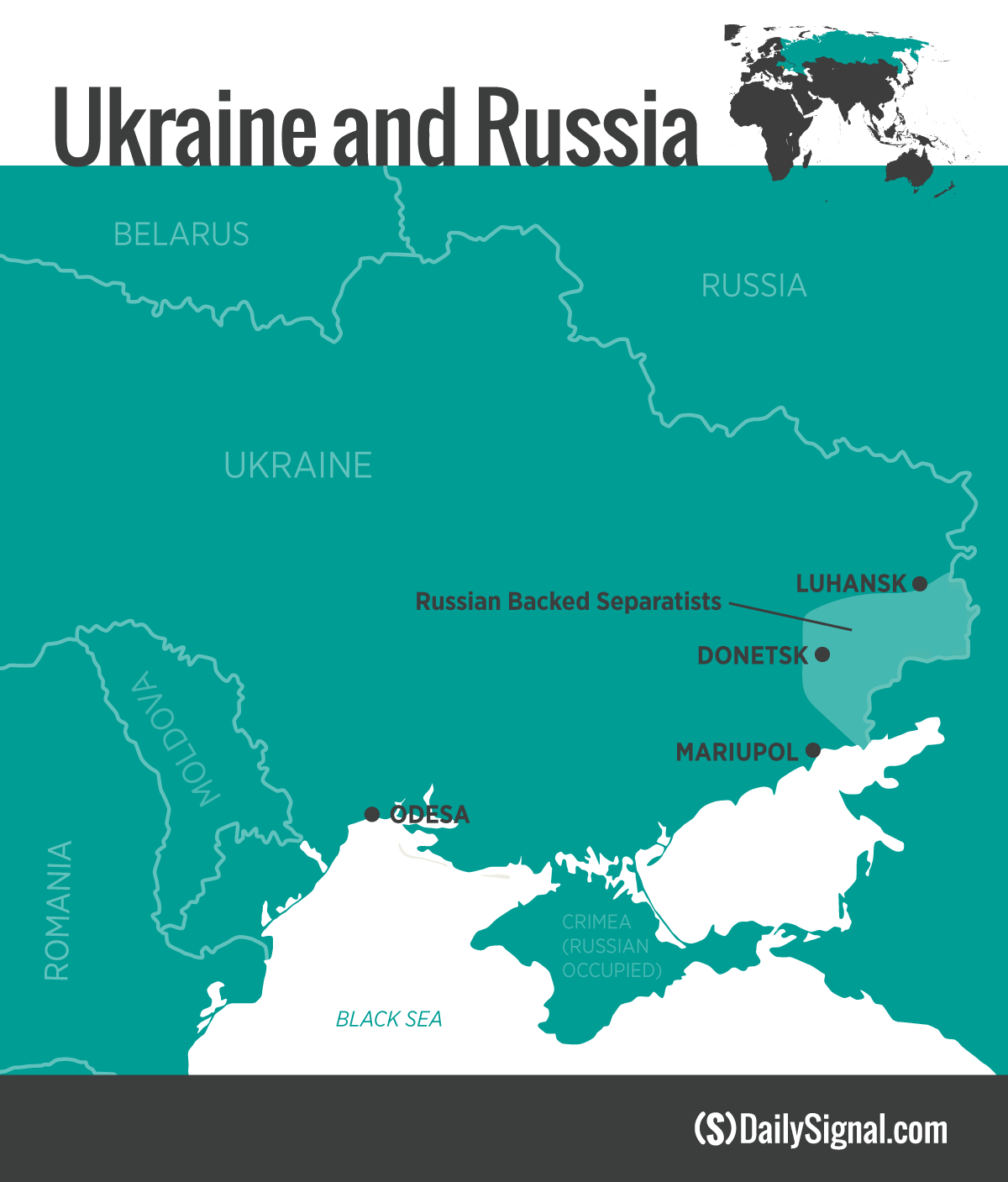

6. Unfinished Business in Ukraine

In 2013, Kremlin-backed Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych refused to sign an association agreement with the European Union, sparking months of street demonstrations that led to his ouster in early 2014.

The subsequent Russian military intervention has left the Crimean Peninsula under occupation and parts of Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts under the control of Russian-backed separatists. The most recent cease-fire between the warring parties (the so-called Minsk II agreement) exists in name only.

Russia’s primary short-term goal there is to keep the conflict in eastern Ukraine “frozen”—meaning that the major fighting stops, without the conflict being brought to a conclusive end.

Another plausible scenario: Moscow helps the separatists consolidate gains in Donetsk and Luhansk to create a political entity that functions more like a viable state. This would include the capture of important communication and transit nodes, such as the city of Mariupol and its port, and the Luhansk power plant—all of which are under Ukrainian government control.

The most aggressive scenario might see Moscow attempt to re-establish control of the Novorossiya region in southern Ukraine. This would create a land bridge between Russia and Crimea—eventually linking up with the Russian-occupied Transnistria in Moldova (and Gagauzia if the scenario plays out).

But taking control would be no easy undertaking, requiring capture of the heavily defended cities of Mariupol and Odesa, Ukraine’s 10th- and third-largest cities, respectively.

***

Considering Russia’s recent track record, any of these scenarios are possible.

Sometimes to understand the present, we must better understand the past. In the 19th century, Victorian statesman and Prime Minister Lord Palmerston summed up Russia’s behavior this way:

The policy and practice of the Russian government has always been to push forward its encroachments as fast and as far as the apathy or want of firmness of other governments would allow it to go, but always to stop and retire when it met with decided resistance and then to wait for the next favorable opportunity.

Some things never change. Palmerston’s description of 19th-century Russia fits Putin’s Russia to a tee.

Russia’s actions in Ukraine over the past couple of years have been deliberate and calculated—part of Putin’s Grand Strategy. The events in Crimea are rooted in the failure of the Obama administration’s Russian “reset,” the unilateral disarming of Europe, and U.S. disengagement from Europe.

Russia has exploited the situation nimbly, calculating that the West will not (or worse, cannot) respond in any significant way.

As Lord Palmerston knew, Russia will do what it knows it can get away with—no more and no less. It is through this lens the West should see the problem and develop its own strategy.