This past spring, Netflix—the beloved online video streaming service—announced it would raise its monthly subscription fees.

The first price hike in June cost between $1 and $2 per month. One consumer was angry enough to file a class action lawsuit. This discontent is typical when consumers feel the impact of higher payments directly. But when costs go up and effects aren’t felt for a long time, that same sense of outrage isn’t there.

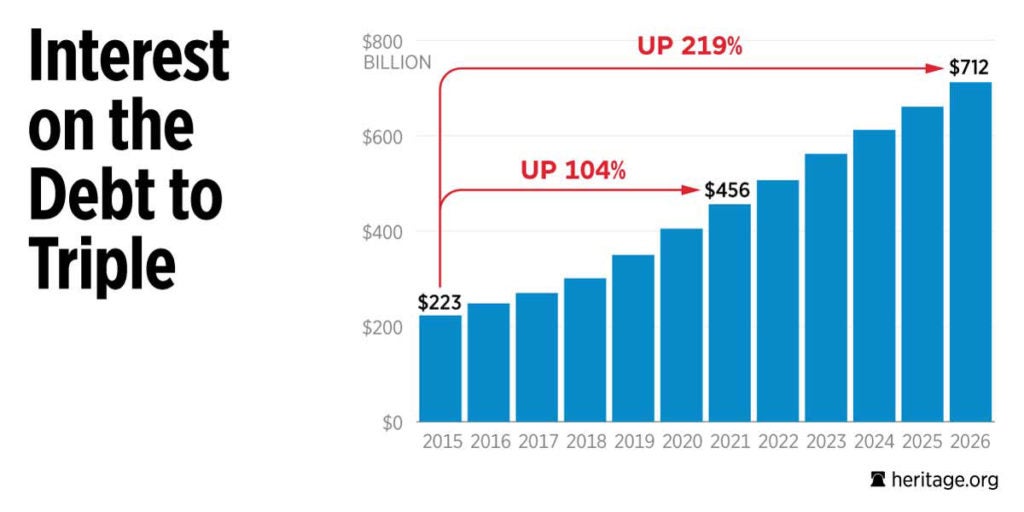

Consider the massive increase in interest costs on the national debt projected over the next decade. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that interest payments on the national debt will double in fewer than five years and triple before the end of the decade. Where’s the public outrage now?

In 2015, the United States government spent $223 billion in tax dollars just to service the national debt. This spike in debt-servicing costs will have serious and negative impacts on American families and the economy in the long run.

High public debt has been shown to slow down economic growth and to exert upward pressure on interest rates. Slow economic growth reduces employment and business prospects for American families, and it has a negative effect on family incomes and wealth.

As national debt and interest payments swell, investors may question the United States’ ability to repay its loans. This could raise interest rates and lead the government to collect more taxes in order to service the national debt.

To put debt-servicing costs in context, the federal budget is separated into three main spending categories: mandatory, discretionary, and net interest. Net interest is the difference between what the government pays to service the publicly held national debt and what is earned from government-issued loans. As net interest spending grows, the other portions of the budget shrink.

Every dollar spent servicing the debt is a dollar that cannot be used for another purpose, and these massive net interest payments will crowd out other vital national priorities. By 2023, spending on net interest payments will surpass spending on national defense.

Interest payments are determined by the size of the U.S. debt and market-driven interest rates. Since the federal government is legally obligated to repay lenders, interest on the debt is automatically paid every year, regardless of how much it costs.

This means that the only way to truly control net interest payments is to control the deficit and national debt.

But this is already something Congress should be working to do. Reducing spending and debt is critical, as a large debt is a detriment to America’s economic future. If Congress is going to get a handle on net interest payments and the national debt as a whole, it must tackle mandatory entitlement programs like Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security, which are the largest drivers of federal spending.

Every time lawmakers approve more spending and take on more debt, it’s imperative that they understand taxpayers will be paying for it—in the form of debt servicing—for a long time to come.

Sure, government interest costs may not seem to impact everyday life as much as paying that extra dollar to watch “House of Cards.” But ballooning net interest costs will catch up to American families. Congress should make spending reductions that reduce the debt and put the budget back on a path to balance.

For this and other charts about the federal budget, check out The Heritage Foundation’s Federal Budget in Pictures.