Deirdre Folley is one of more than 600,000 people nationwide who is considered uninsured.

Yet when her daughter suffered a hairline fracture in her leg, requiring visits to an urgent care center, radiologist, and orthopedist, Folley and her family didn’t end up paying anything for the cost of her care even though charges totaled nearly $1,400.

That’s because Folley and her family of four are members of Samaritan Ministries, a health care sharing ministry with members who “share” in the cost of one another’s medical expenses.

Folley, who lives in New Hampshire, is one of the more than 200,000 members of Samaritan Ministries, a Christian-based organization that is one of the three major health care sharing ministries.

Nationwide, membership in health care sharing organizations tops 600,000 people, according to the Alliance of Health Care Sharing Ministries.

Folley, who has blogged about her experiences with Samaritan Ministries, first joined the health care sharing organization in April 2014.

Folley’s family was previously insured through her husband’s employer, but after the couple decided her husband would go back to school, they knew they would have to explore other health care options.

“In our situation, leaving a job, going into being a student and a homemaker and not having any type of benefits, either you’re going to be left out in the cold or you’re going to be doing something like this,” she told The Daily Signal. “Of course, now it’s illegal to be out in the cold, and we knew we weren’t interested in Obamacare.”

A friend of Folley’s husband originally told them about Samaritan Ministries, and when they began to research the organization, the couple was pleased with what they found.

Health care sharing ministries facilitate the sharing of medical costs between members, all of whom have shared beliefs.

The ministries don’t serve as insurance, but rather when a member has a medical “need,” other members “share” that person’s medical costs.

In some ministries, like Samaritan, members are encouraged to negotiate prices directly with providers to bring down the cost of their medical bills, like Folley did, and they pay in cash before being reimbursed by members of the health care sharing ministry.

For Folley, one of the most attractive parts of the health care sharing ministry was the fact that the organizations are exempt from Obamacare’s individual mandate, so members aren’t subject to the annual fine for going uninsured.

Folley said she and her husband are opposed to socialized medicine and didn’t have confidence in the government’s ability to manage their health care.

But most importantly, because health care sharing organizations are exempt from the requirements the Affordable Care Act places on insurance policies, Folley said it protected her and her husband, who are devout Catholics, from crossing any ethical boundaries.

“We didn’t want to buy into a plan where we were most likely going to be paying for abortions or not knowing whether or not we were paying for abortions,” she said, continuing:

With Samaritan, we know we don’t pay for anyone’s abortions, we don’t pay for contraception, we don’t pay for sex changes or counseling for things we would object to. We know that our money isn’t taking part in anything that we have a moral objection to.

An ‘Alternative’

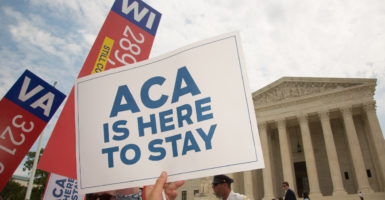

Health care sharing organizations have existed for more than 20 years, but membership has grown substantially since Obamacare’s first open enrollment period launched in October 2013.

Samaritan Ministries, of which Folley is a member, has seen its enrollment nearly triple in that time.

In January 2013, the organization had 64,721 members. By September 2016, its membership had grown to more than 207,000 members, according to the organization.

Christ Medicus Foundation’s CURO, a Catholic health care sharing ministry that partners with Samaritan, launched in 2014 and has grown to have 900 member households, comprised of more than 2,500 individual members, the organization estimates.

Similarly, enrollment in Medi-Share, another health care sharing ministry, more than tripled.

Medi-Share had 59,855 members in June 2013, according to the organization. By June 2016, the health care sharing ministry boasted 200,333 members.

Anthony Hopp, vice president of external relations for Samaritan Ministries, said 2013—when Obamacare’s exchanges launched—was a “pivotal year” for membership growth.

“The Affordable Care Act increased awareness of health care sharing ministries in general,” Hopp told The Daily Signal. “We pretty much collectively, all of the health care sharing organizations, were off the radar for the most part. Then, with the insertion of the exemption, a lot of news outlets picked this up, and whether we wanted to be or not, we were kind of thrust into everybody’s minds.”

The ministries are expecting to see their enrollment continue to grow, particularly as issues continue to arise with the Affordable Care Act.

“It’s lower cost. It’s personal accountability. It lets you see everything you’re doing and the decisions you’re making,” Twila Brase, president of the Citizens’ Council for Health Freedom, told The Daily Signal of the organizations.

Health care sharing ministries are adamant in that their organizations are not insurance, but rather serve as an alternative to the Affordable Care Act.

“The Affordable Care Act provided a lot of different ways for people to meet their health care needs. We view ourselves as just one option—we’re an alternative to health insurance,” Michael Gardner, director of communications at Medi-Share, told The Daily Signal.

“People value the community. That’s one of the key things,” he continued. “It’s a community of like-minded people who come together based on a set of beliefs to share each other’s medical burdens.”

Louis Brown, director of CMF CURO, said the health care sharing ministry started as the “Catholic response to the needs and suffering of today within American health care.”

Like Gardner, Brown said the first thing his organization tells prospective members is that they are not offering insurance, but rather a way for people of the same faith to come together to take care of one another.

“We believe as Catholics that problems are best solved closest to the problem, and here, we are able to solve this problem of medical costs and medical needs and health care needs, this issue of healing, and we’re able to do that as a community of faith coming together across the country,” Brown told The Daily Signal. “It works, and it’s less expensive, and it’s consistent with your faith.”

Prospective members must adhere to a series of guidelines to join health care sharing organizations, which are traditionally in keeping with biblical teachings. Guidelines differ among health care sharing ministries, but many require members to remain drug-free, drink only in moderation, attend church on Sundays, and abstain from sexual activity outside of marriage.

Each month, members “share” in the cost of medical bills through a set monthly payment, and the organizations place restrictions on which sorts of medical costs constitute “needs.”

For example, medical services for pre-existing conditions are often excluded, as are routine physicals and preventive care.

Folley and her family pay $495 per month as members of Samaritan.

The family receives the name of another member to send their “share” to, and Folley typically includes notes of encouragement to the member, and includes him or her in the family’s prayers.

“It is really good to know you’re part of a body of people who are on the same page,” Folley said. “We have received very kind and sweet notes from other people when we’ve been receiving and definitely had a strong sense of them praying for us and knowing they care even though they don’t know us at all.”

Folley and her family have had to submit a “need” four times since joining Samaritan, including one for the birth of her son and another for her daughter’s broken leg.

Each time, the family received “shares” from other Samaritan members, along with notes of encouragement.

“The philosophy at Samaritan is very much promoting independence and taking care of yourself, but also subsidiarity and taking care of your Christian brothers and sisters and relying on the church rather than the state,” Folley said.

Not Without Controversy

Though health care sharing ministries have been functioning for more than 20 years, critics warn that there is no guarantee that medical bills will be paid for.

The National Association of Insurance Commissioners has previously warned that health care sharing ministries are not insurance and therefore don’t have the protections of insurance.

But the health care sharing organizations don’t shy away from admitting that those critics are right.

“When they’re digging at, ‘well there’s no guarantee, there’s no guarantee,’ we don’t argue that. There isn’t,” Hopp, of Samaritan Ministries, told The Daily Signal. “But Samaritan, our core principle is that Jesus Christ is the provider of all our needs. Our mindset is not that Samaritan is a panacea for any and every medical need. That’s not the purpose. This is simply one way that God has used to meet the needs of his people.”

In the past, there have been issues surrounding unpaid medical claims and lawsuits filed by members.

In 2004, three years after their removal from ministry leadership – and with new ministry managers in place – the founder of Christian Brotherhood Newsletter and his family were found liable by an Ohio jury for nearly $15 million in damages to the ministry. The lawsuit was brought by the ministry itself and the Ohio attorney general’s office for diverting money from the organization and an affiliated mission. Before the previous managers were removed, members of the newsletter had amassed $28 million in unpaid medical bills, which the ministry, under its new leadership, paid.

Additionally, Medi-Share members in Montana, Oklahoma, and Nevada sued the health care sharing ministry in the last 10 years over refusal to pay medical bills they argued should’ve been covered.

Gardner, of Medi-Share, said prospective members need to be sure to fully understand which medical services are eligible for sharing and stressed that there is no guarantee of payment because the organizations are not insurance.

“That’s one thing people should be sure to ask about if they’re considering a ministry,” he said.

At Samaritan, members vote on which medical services can be shared, Hopp said.

If an individual disagrees with Samaritan’s guidelines on which medical services can be shared, the decision can be appealed to a 13-member panel of randomly selected members for arbitration.

Since the ministry was founded in 1994, Hopp said the arbitration process has only been used four times.

“I’m not aware of any insurance company that has that consumer protection,” he said.

‘Liberating’

Folley, the Samaritan member, said that the idea of membership in a health care sharing ministry may not cross people’s minds until they are left without benefits, as her family was after her husband decided to return to school.

“Once you’re out of that paradigm and you look into it, you realize what a great option it is, and it’s even better than most really good insurance plans,” she said. “I know we spend less money … Even compared to a good insurance plan, it’s better.”

Since joining Samaritan, Folley said she’s found herself immune from some of the complaints consumers with insurance have had in the wake of Obamacare’s implementation: rising premiums and deductibles, narrowing networks, and the inability to keep a prior doctor.

“I get to sidestep all of that,” she said. “It’s incredibly liberating. I think, ‘poor them.’ I don’t deal with any of that.”

Hopp said Samaritan typically raises its monthly “shares” once every two to two and a half years through a vote its members take, with the most recent increase to $495 a boost from $405.

Folley has had the freedom to choose which doctors she wants to use, she said, which is beneficial for Folley since she has self-described “alternative views” on health care.

And the monthly “share” she does make to fellow Samaritan members doesn’t feel like a bill to her.

“Because you send your money directly to someone who needs it to pay back their medical bills, it doesn’t feel like paying a bill. It feels like charity,” Folley said. “It feels like OK, this person needs this $400 from me. I have to do that, because I know they would do that for me.”

This article has been updated to include recent enrollment figures from Samaritan Ministries. It was also corrected to clarify the verdict and damages against the founder of Christian Brotherhood Newsletter and his family, as well as their unpaid medical bills.