MARIUPOL, Ukraine— For more than two years, Ukraine’s military has been fighting a ground war against a combined force of pro-Russian separatists and Russian regulars in the Donbas, Ukraine’s embattled southeastern territory.

As Ukraine prepares for the 25th anniversary of its independence from the Soviet Union this Wednesday, the ongoing war in the Donbas highlights how the post-Soviet country is still fighting to establish its freedom from Russian vassalage.

“The dream of Ukrainian independence existed in the USSR, but we couldn’t talk about it,” Kovbel Vasyl Vasyliyovych, a 62-year-old Ukrainian soldier, told The Daily Signal. “The environment was one in which you only tried to survive. You didn’t express yourself. I feel like now I can finally express sentiments that I’ve had bottled up inside me my whole life.”

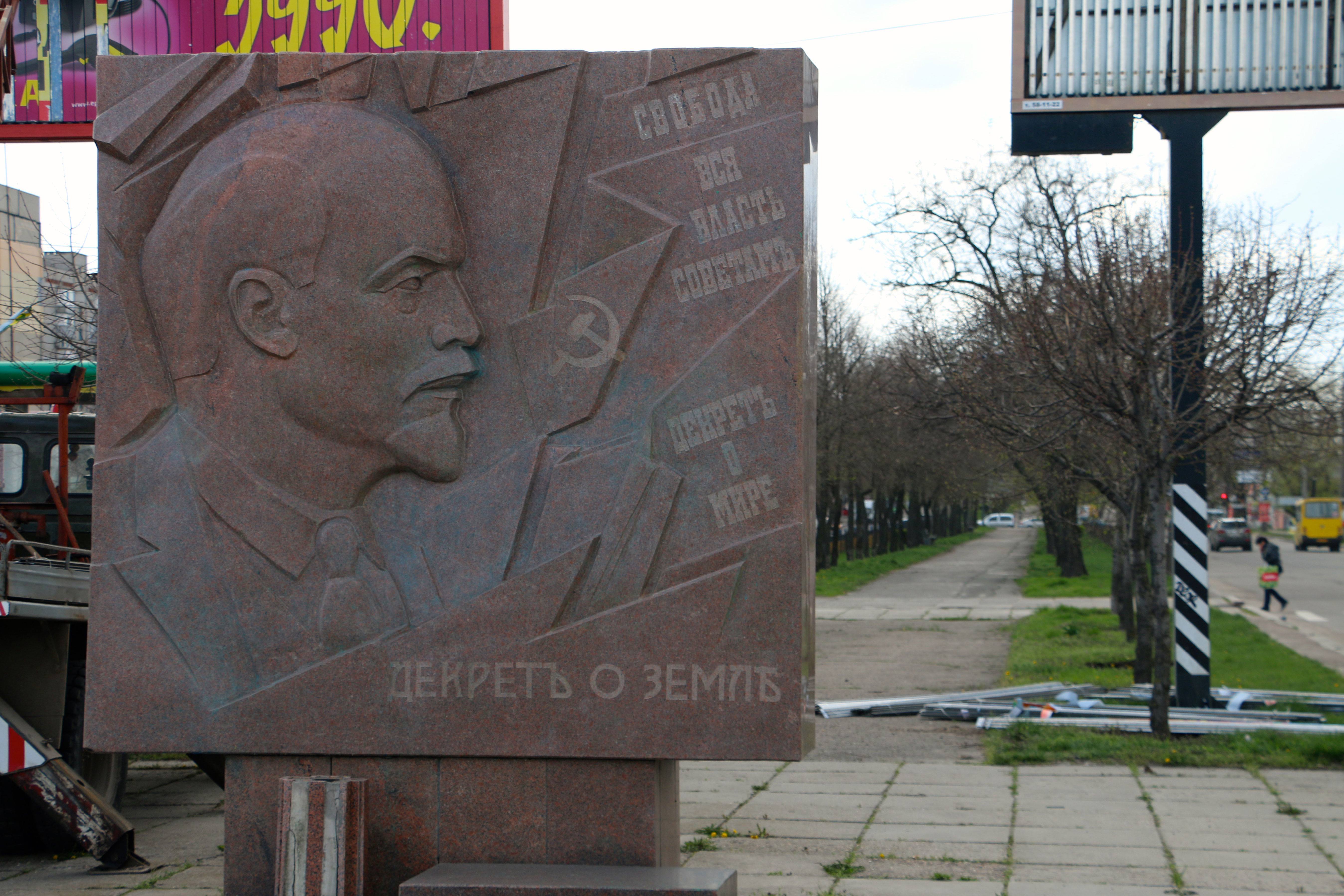

A Ukrainian flag tops a Soviet-era war memorial in the eastern Ukrainian city of Kharkiv. (Photos: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

The war in Ukraine is a bizarre, paradoxical fusion of antiquated fighting methods with modern technology. It is a trench warfare battle, where heavy artillery is fired every day and drones orbit overhead. Small units engage each other in no man’s land, but there are no serious attempts to take new ground. The war is static, governed in its intensity by the terms of the Minsk II cease-fire. It’s like two boxers sparring at half speed, sparing themselves for the main event.

It has been nearly 100 years since the Russian Civil War began, sparking events that led to the consolidation of Ukraine into the Soviet Union—a loss of independence that lasted until Aug. 24, 1991. Today, many Ukrainian soldiers say they are still fighting for Ukraine’s independence from Moscow.

“The separatists are the weapons of the Russians,” Borys Antonovich Melnyk, a 75-year-old Ukrainian volunteer soldier and Red Army veteran, said in an interview.

“They were turned by Russian propaganda against Ukraine,” Melnyk said. “They are Russia’s weapons. They are the weapons, not the reasons. This is not only a war against the separatists, this is a war against Russia.”

It has also been about 100 years since combat airpower made its debut over the trenches in World War I. Today, Ukraine’s air force now sits on the ground while its soldiers dodge artillery and tank shots.

And despite the front lines ending on the Sea of Azov, there is no naval component to the war, either.

The last major offensive in the war was in February 2015. In the days after the signing of the second cease-fire, known as Minsk II, combined Russian-separatist forces sacked the strategic rail hub town of Debaltseve, seizing it from Ukrainian government control.

Since the Debaltseve battle, periodic upticks in violence predictably spur flurries of media speculation about whether a major Russian offensive is looming. Yet, the war has not changed in any meaningful way in more than a year and a half. No significant territory has changed hands, and the opposing camps have made scant progress toward achieving a diplomatic solution to the conflict.

And periodic spats between Kyiv and Moscow, such as the Aug. 10 border skirmishes in Crimea, underscore how the conflict retains the potential to quickly spiral into something much worse.

>>>After Crimea ‘Incursions,’ Russia and Ukraine Step Back From All-Out War

Today, U.S. and Ukrainian intelligence sources estimate the combined Russian-separatist army has about 45,000 troops inside Ukrainian territory, with about 45,000 more Russian soldiers staged in Russia along the western border with Ukraine. Russia also has about 45,000 military personnel stationed inside occupied Crimea. Ukraine has deployed about 100,000 soldiers to its eastern territories.

“The Russian people are not the enemy,” Vasyliyovych said. “Half of my relatives and friends live in Russia. It’s a political war. The Soviet propaganda is still there. And [Russian President Vladimir] Putin still uses it the same way as they did in the USSR.”

Ad Hoc War

The Ukrainian army’s 92nd Brigade is hunkered down in trenches and in the basements of abandoned homes scattered throughout the artillery-blasted ruins of the village of Pisky, on the outskirts of the separatist-controlled Donetsk airport in eastern Ukraine.

Squads of Ukrainian soldiers on patrol carry at least one radio among them. The radio, usually an off-the-shelf Motorola, is their advance warning system for incoming artillery.

Spotters posted in front-line trenches continuously peer across no man’s land through binoculars and telescopes. When they observe artillery fired in the Ukrainians’ direction, they have a few precious instants to radio a warning—the word “hole”—on a common frequency. That’s the cue for all who hear it to take cover or to lay down flat on the ground if caught in the open.

The radios the Ukrainian soldiers use are not encrypted. Therefore, they share the airwaves with their enemies. Due to the lack of encrypted radios and how frequently Ukrainians change their positions, which precludes setting up hardline communications, the Ukrainians sometimes use runners to carry handwritten messages scribbled on sheets of torn paper among various front-line posts.

In calm periods of bemusement, the Ukrainian troops listen to radio chatter transmitted from the opposite side of no man’s land; they pick out Russian accents from Moscow, or St. Petersburg. The Ukrainians often chime in on the radio, employing the full breadth of the Russian language’s copious lexicon of curse words to taunt and mock their enemies.

At night, the dark sky is cut by the streaking red lights of tracer fire. And there is the frequent whirring sound from the motors of Russian drones orbiting overhead. The Ukrainian soldiers call them “sputniks.”

“The dream of Ukrainian independence existed in the USSR, but we couldn’t talk about it,” 62-year-old Ukrainian soldier Kovbel Vasyl Vasyliyovych said.

During downtime, the soldiers scroll through their Facebook pages on their smartphones. They listen to music or watch movies on their laptops. They try not to cluster together when on their cellphones, however, due to reports of Russian signals technology that can pick out clusters of cell signals as a way to target artillery.

The soldiers use an app, loaded onto a tablet and developed by university students in Kyiv, for plotting enemy artillery positions on a Google Earth map of the battlespace.

Without the possibility of airborne medevac, ground evacuation is the only hope for survival if a soldier is wounded. Understanding the long odds against survival if wounded severely, many Ukrainian soldiers carry a grenade under their body armor as a means to commit suicide if they are ever mortally wounded.

During the day, tanks on both sides periodically come out from their camouflaged hiding spots to lob a few artillery rounds across no man’s land. Snipers take frequent potshots, and other weapons like automatic grenade launchers are often used.

In 2012, Ukraine was the world’s fourth largest arms exporter, selling more than $1.344 billion worth of conventional arms, according to a report from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Kovbel Vasyl Vasyliyovych hugs a civilian volunteer goodbye at a base near the front lines in eastern Ukraine.

Yet, apart from weapons and ammunition, almost all of the Ukrainian soldiers’ kits, food, and clothing are brought to the front lines by civilian volunteers. Many Ukrainian soldiers have used their own money to buy uniforms and body armor off the internet. One soldier said his wife gave him a body armor vest for his birthday.

Civilian volunteer groups raise money from internet campaigns to purchase items like individual first aid kits, sleeping bags, boots, and food for soldiers deployed to the front lines. Volunteers, usually with no military training, deliver these supplies, exposing themselves to the same risks of artillery and sniper fire as the soldiers they are supporting.

One Dimensional Fight

The southern terminus of the front lines is in the seaside town of Shyrokyne, on the Sea of Azov.

In the industrial city of Mariupol, about 20 minutes by car west of the front, the beaches are lined with troop barricades, barbed wire, and mines. It is a scene reminiscent of fortifications in Normandy during World War II.

Separatist territory comprises about 20 miles of shoreline on the Sea of Azov (running from Shyrokyne to the Russian border), but there is currently no naval dimension to the conflict.

Air power is also almost nonexistent. The Ukrainian air force was grounded as a condition of the first cease-fire signed in September 2014. The Donbas is now among the most heavily defended airspaces on Earth. The area is replete with modern Russian surface-to-air missile systems, posing a grave threat to Ukraine’s Cold War-era warplanes.

The July 17, 2014, downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 over separatist-held territory by a Russian BUK surface-to-air missile, killing all 288 people aboard, highlighted the threat to aircraft in the region.

Three days prior to the downing of MH17, a Ukrainian An-26 transport plane flying at more than 21,000 feet over eastern Ukraine was brought down by a surface-to-air missile—the crew survived. A month earlier, on June 14, 2014, a Ukrainian IL-76 transport plane was shot down near the Luhansk airport in separatist-controlled territory, killing 49 soldiers and crew.

According to news reports, combined Russian-separatist forces shot down seven Ukrainian fighter and attack aircraft, three transport aircraft, and at least nine helicopters over eastern Ukraine prior to the first cease-fire.

Ukraine has not lost any aircraft to enemy fire after September 2014 due to the halt in air operations. Yet, according to the Ukrainian military, Russian air defense forces are still moving into eastern Ukraine.

On Saturday, the Ukrainian Defense Ministry’s Main Intelligence Directorate reported that Russia had deployed a mobile air defense division to the Donbas, comprising 12 TOR-M2U short-range air defense missile systems and 170 personnel.

Additionally, combined Russian-separatist forces in eastern Ukraine currently have more tanks than the arsenals of France and the United Kingdom put together, according to Ukrainian defense officials.

Life Goes On

In Ukraine’s capital of Kyiv one would hardly know there was a land war going on within a day’s drive from the city’s bustling cafés and restaurants. There are new art spaces popping up across town, live music in the bars, festivals in the streets. It feels like a carefree summer in any European capital.

Kyiv’s main thoroughfare, Khreshchatyk, will be closed for a military parade on Wednesday as part of Independence Day celebrations.

Many Ukrainian soldiers admit they don’t want civilian life to grind to a halt because of the war. They say it is a testament to their military service and the promise of the 2014 revolution that normal life carries on despite the war.

Kyiv’s ubiquitous hipsters, the new coffee shops, the packed arena concerts featuring bands like the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Muse make it feel like the revolution’s promise of a more Western European way of life is inching toward reality. Ukrainian millennials wishfully describe Kyiv as the “New Berlin.”

Yet, beneath the surface, life is harder in Ukraine than it was prior to the 2014 revolution. The country’s economy is struggling. Wages have remained stagnant despite the fact that the hryvnia, Ukraine’s national currency, has plummeted to less than a third of its pre-revolution value against the dollar.

Corruption is still rampant, from government halls to the minutia of daily life, like getting in to see a doctor. And the war is no closer to a long-term solution today than when the second cease-fire was signed on Feb. 12, 2015, more than a year and a half ago.

The conflict is quarantined to the Donbas region, which comprises less than 15 percent of Ukraine’s total landmass. And for many Ukrainians, the day-to-day hardships of the economic downturn trump concerns about the conflict, which has little tangible impact on daily life outside of the war zone. News reports from the front lines have consequently faded from Ukraine’s domestic headlines.

Waning public attention to the war has left many returning veterans feeling isolated and frustrated when they return home. There is a feeling among many veterans and active-duty soldiers that they are fighting in a forgotten war. Not only forgotten by the world’s media, but by Ukrainians themselves.

“The war won’t be over soon,” Melnyk, the 75-year-old Ukrainian soldier, said. “I don’t know when. Maybe Putin knows. Maybe [Ukrainian President Petro] Poroshenko knows. But I don’t think it will be over soon.”