How many non-teachers does a school district need?

Since 1950, public schools all across America have added staff at a rapid rate—much faster than their increases in students.

Sure, there have been some increases in lead teachers that resulted in large declines in class sizes. However, there were even greater increases in the hiring of administrators and all other staff over these six-plus decades.

Given the prior exclusions of special needs students from public schools and other historic inequities within the public education system, perhaps these dramatic staffing increases were warranted in the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, the 1980s, and into the 1990s.

But, these increases in staffing—especially in administrators and others who are not teachers—are still going on all around the country, including in the District of Columbia.

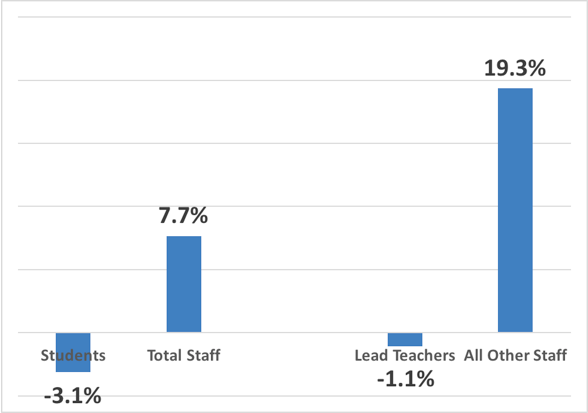

According to data that the District of Columbia Public Schools submitted to the U.S. Department of Education, the District’s public schools experienced a 3.1 percent decline in its student population between the 1993-94 and 2013-14 school years. Despite this decline in students, D.C. Public Schools increased its staffing by 7.7 percent (all increases are in full-time equivalents).

Source: Digest of Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, 2015 Digest Tables 203.40 and 213.20 and 1996 Digest Tables 41 and 83.

Who were these new D.C. Public Schools staff?

Well, the teaching force declined by 1.1 percent over this period.

While the number of students and teachers were declining, D.C. Public Schools increased its employment of administrators and all other staff (all those who were not lead teachers) by a whopping 19.3 percent.

Put differently, as shown on the chart below, while the number of students they served was declining, D.C. public schools increased administrators and others who are not lead teachers by almost 20 percent.

For historical context, this tremendous increase in D.C. Public Schools staff who are not lead teachers since 1993 came after a decades-long staffing surge, where both teachers and especially administrators and other employees were added at rates far above increases in students.

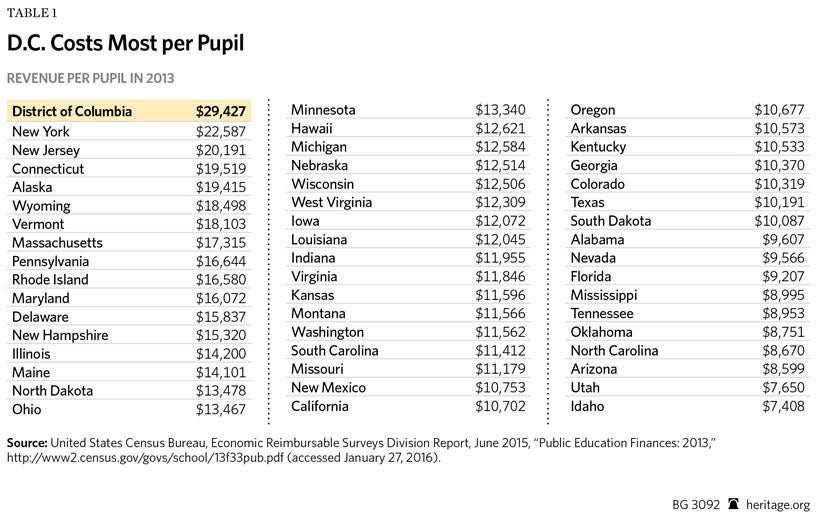

This staffing surge may give us insight into why D.C. Public Schools have the highest per-pupil revenue in the country, at $29,400 per student per year.

The long-term bloat of public school staff in the District of Columbia shows that parents across the country need innovative and more effective ways to control education spending for their children, instead of letting the school district continue to fritter it away with hiring non-lead-teachers. As researcher Matthew Ladner has documented, those students who choose to attend private school instead of the struggling public schools in D.C. get far less money to spend on their education:

From an equity standpoint, it is difficult to justify the District’s school finance system. The system routinely provides $29,000 for high-income students attending regular public schools. It provides $14,000 for high-income students attending charter schools but only a maximum of $8,381 for some low-income students who would like to attend a private school system that improves the chances for graduation by approximately 21 percentage points.

Ladner concluded, “Instead of attempting to restructure or ‘reform’ [D.C. Public Schools], policymakers should free District parents to reform education from the bottom up.”

Students in the nation’s capital would be much better served by empowering them with control over their share of education funding through a system of universal education savings accounts Through this option, parents would receive a portion of the funds spent on their child in the traditional public school system, and could then use those funds to pay for a variety of education-related services, products, and providers, including private school tuition, online learning, special education services and therapies, textbooks, and host of other products.

Instead of financing bloat and relegating students to schools that might not be meeting their unique learning needs, a system of universal education savings accounts in the District would empower families to match learning options to their children’s unique needs, and enable them to allocate existing resources better.

As economist Milton Friedman explained, the public school bureaucracy, by its very nature, engages in what he called category four spending—the worst type of spending—whereby someone spends somebody else’s money on somebody else. That is, public schools spend somebody else’s money (taxpayer dollars) on somebody else’s kids.

As Jason Bedrick and one of us (Lindsey) explain:

Public-school officials, like all government bureaucrats, primarily engage in the worst kind of spending: They spend other people’s money on children who are not their own. As competent and well-meaning as they may be, their incentives to economize and maximize value are simply not as strong as those of parents spending their own money on their own children…. Though education savings accounts are still taxpayer funded, the way they are structured makes for a dynamic closer to the one involved in spending your own money on your own children: Parents still insist on the best quality education but have more incentive to find a bargain.

That mindset helps explain why D.C. is spending so much on administrative positions in recent years: D.C. bureaucrats don’t have the same urgency parents do to make sure each child receives the best education possible, and that the financial resources used are spent to maximize the child’s education.

Administrative bloat over time in the District is just one more indicator that a K-12 education financing system that funds the child – not school systems – can better serve students and taxpayers.

Lindsey Burke is the Will Skillman Fellow in Education Policy at Heritage. Benjamin Scafidi is a professor of economics in the Coles College of Business at Kennesaw State University.