The 75 police officers of the Parker Police Department favor wearing cameras on their body to capture encounters with citizens.

“I don’t know if you could find one officer who would want to go back to not having body cameras,” said Cmdr. Chris Peters, who designed Parker’s body camera program, which is approaching its one-year anniversary in September. “Any officer who is doing the right thing on a daily basis would want to have a camera on them. What the camera provides is an unbiased third-party account, and helps reduce the amount of questions of what happened.”

The fatal police shootings of black men in Louisiana and Minnesota earlier this month have renewed focus on the debate over supervising police and citizen interactions.

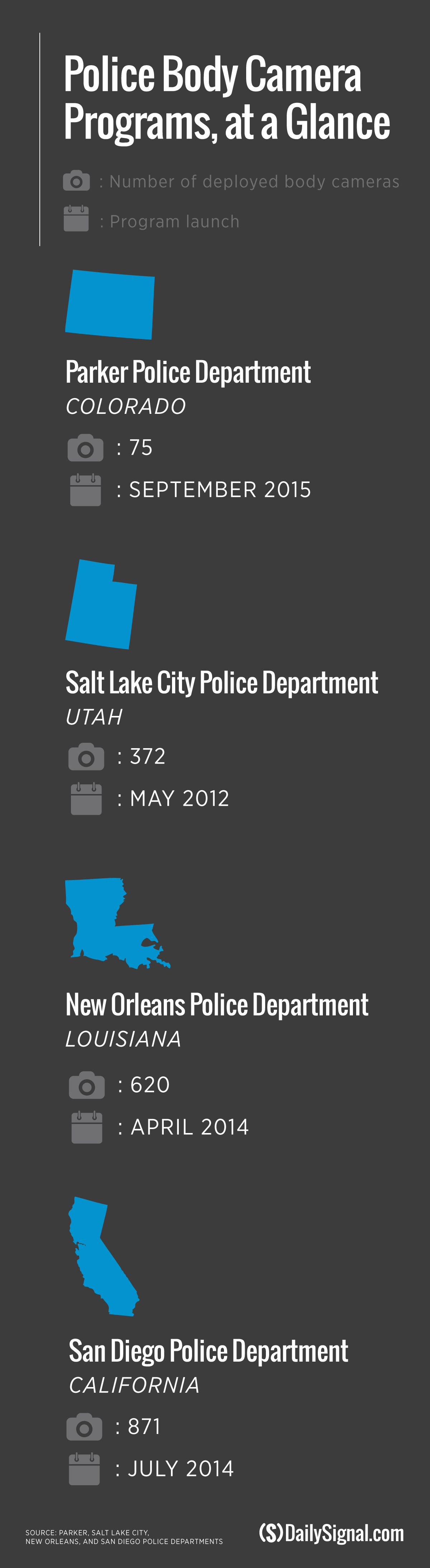

Even before those incidents, the Parker Police Department, a small force representing 50,000 people in a mostly white, affluent suburb of Denver, was not the only law enforcement agency embracing body cameras.

Some, like the Salt Lake City Police Department, acted even before the fatal police shooting two years ago of a black teenager in Ferguson, Missouri. The officer was not charged in that case, and critics argued that had he worn a body camera, there would have been a clearer account of what happened.

In May 2012, the Salt Lake City Police Department, which serves Utah’s capital city and its large Latino and refugee population, equipped two patrol officers with body cameras.

Today, 372 officers wear cameras—including detectives—attaching them to their collar, helmet, or sunglasses.

>>>Personal Experience Convinced Sen. Tim Scott on Need for Police Body Cameras

The cameras have proven not only popular but successful, the department says, in helping limit the kind of forceful interactions between police and citizens that have sparked a divide between law enforcement and minority communities.

“When we talk to our officers about body cameras, we tell them we have to be transparent with our community,” said Salt Lake City’s Assistant Police Chief Tim Doubt, who noted that use of force complaints from citizens have dropped from 40-50 per year in 2008 to 2010, to six in 2014, and 18 last year.

“We are part of the community, they are part of us, and we have to show them that the bad things that come out on YouTube from cellphone video are outliers,” Doubt added. “In this country we’ve lost trust in the last couple of years with the public, and that body camera helps tell more of the truth.”

Early Results

Though research is in its infancy, some studies have shown that the use of body cameras can reduce use of force by officers and complaints by the public.

The San Diego Police Department is a rare agency that has released a study on its body camera program.

In July 2014, the department deployed cameras to 871 officers. A first-year investigation of the program revealed mixed results.

According to a copy of the study obtained by The Daily Signal, citizen complaints against officers decreased 23 percent from the year before the department began using body cameras, to a year after.

However, officer use of force incidents increased 10 percent in that time period.

Meanwhile, a study of the Rialto Police Department in California showed that when officers began using body cameras, use of force by police dropped 59 percent, and citizen complaints against them fell 87 percent.

Travis Easter, the media relations coordinator for the San Diego Police Department, said it’s too early to connect body cameras to police and citizen behavior.

But Easter, who used to wear a body camera when he worked in the field, said it’s not too soon to try and make a difference.

“Everytime I contact somebody I have an affect on their opinion of law enforcement, whether good or bad,” Easter told The Daily Signal. “That can change given how the contact with an officer goes. If officers and citizens are being watched, we are both more liable to do the right thing.”

Policy Pickle

But as body cameras become an accepted norm of modern policing, law enforcement agencies are facing challenges over related issues such as privacy, transparency, and performance.

The trickiness of body cameras was shown during last week’s deadly police shooting of Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Police officials said after the shooting that body cameras worn by the two police officers involved fell out of position during the altercation, resulting in poor quality video unlikely to be useful in an investigation.

In another officer-involved shooting last week, the officer who killed Philando Castile during a traffic stop in Falcon Heights, Minnesota, was not wearing a body camera. Castile’s girlfriend used her phone to film the aftermath of the shooting on Facebook Live.

Technical issues aside, there are other complex questions involving body cameras, including:

Who wears body cameras, and in what circumstances should they be recording?

Who gets to see the video? Assuming the public can view the video, when can they get access to it (before an investigation is completed or after)?

And finally, who creates these policies? How does a state’s public records law interact with police departments that want to set their own standards for releasing body camera video?

The ways in which departments answer these questions will prove crucial in whether body cameras do what they are intended to do—to help settle disputes over controversial police-citizen interactions.

“Police body cameras are never good or bad unto themselves,” said Chad Marlow, a privacy and technology expert at American Civil Liberties Union.

“What determines good or bad is the policy that governs their use,” added Marlow, who has assisted police departments on their body camera policies, including the Parker Police Department. “The challenge in drafting a good body camera policy is we need to strike a balance between promoting policy transparency and accountability and preserving individual privacy. If you go too far in either direction you don’t create a workable or robust policy.”

Public View

Early adopters of body cameras are trying to be proactive in setting clear rules to catch up with the technology.

“We were one of the first to run a program, so when we started working on a policy, no one had a policy we could use as precedent,” said Doubt of the Salt Lake City Police Department, in an interview with The Daily Signal.

Although Salt Lake City has not faced a singular high-profile altercation between the police and the public that swept it to action, Doubt says the department appreciated early the benefits body cameras could provide, both for officers and citizens.

“It can resolve an internal affairs complaint, a criminal case, and of course, it’s evidence,” Doubt said. “We believe 99 percent of cops are doing a great job everyday, and that cameras will show that officers do a good job the majority of the time.”

But the public is constrained in seeing that for themselves.

The Salt Lake County district attorney, Sim Gill, has taken the position that he won’t let the police department publicly release video footage—if he considers it evidence in a case—until after he conducts an investigation of a use of force incident, or officer involved shooting.

“My obligation is the due process rights of everyone,” Gill told The Daily Signal in an interview. “It all goes to classification. If I classify the body camera footage as evidence, and it is material and relevant to prosecution, I have to treat it as evidence [and not release it during the investigation]. If the video is no longer relevant, then of course it should be released before the investigation is finished.”

Doubt says he personally disagrees with delaying the release of video, believing it harms the legitimacy of the investigation.

He says the police department is working on a policy that would reinforce its support for making footage available earlier unless the district attorney can publically justify a compelling reason not to.

“This is me talking—I believe once you get all of those first statements in first three or four days, we should release all that stuff,” Doubt said. “We should release video and reports so people see we are not trying to hide anything.”

Gill said the state’s public records law allows for body camera footage to be private during an active investigation.

While Gill insists he “believes in open transparency,” he says he has to treat body camera footage just like any relevant item in an investigation. And that means limiting when the public can obtain video.

“If we are going to rush and release body camera video, why aren’t we releasing the full confession of a homicide defendant?” Gill said. “Why not release audio tape of a serial rapist? Why not release still photographs of a bloody encounter? Everyone intuitively in the community understands we can’t do that.”

“As a public prosecutor, at least in Salt Lake County, I’ve led the conversation on transparency, and the open release of information, and I absolutely believe that,” Gill added. “It’s not that we don’t release body camera video. It’s really about the right time to release it.”

State Lines

The challenge in Salt Lake City is familiar to Nancy La Vigne, director of Urban Institute’s Justice Policy Center, who helped write a comprehensive database of state laws regarding body cameras.

La Vigne learned that even states that have laws allowing expansive access to public records often have an exception for law enforcement in some manner.

These laws give local law enforcement broad powers to restrict the access to content it controls, including body camera footage, but less freedom to release it.

“My fear is that police departments won’t release the video because of these laws,” La Vigne told The Daily Signal. “To the average citizen, this may make it look like, ‘Well, so much for body cameras; there is no transparency there.’ But most law enforcement under existing statute can withhold this information and arguably rightfully so.”

Some states whose public record laws don’t explicitly reference body camera footage are creating policy that does.

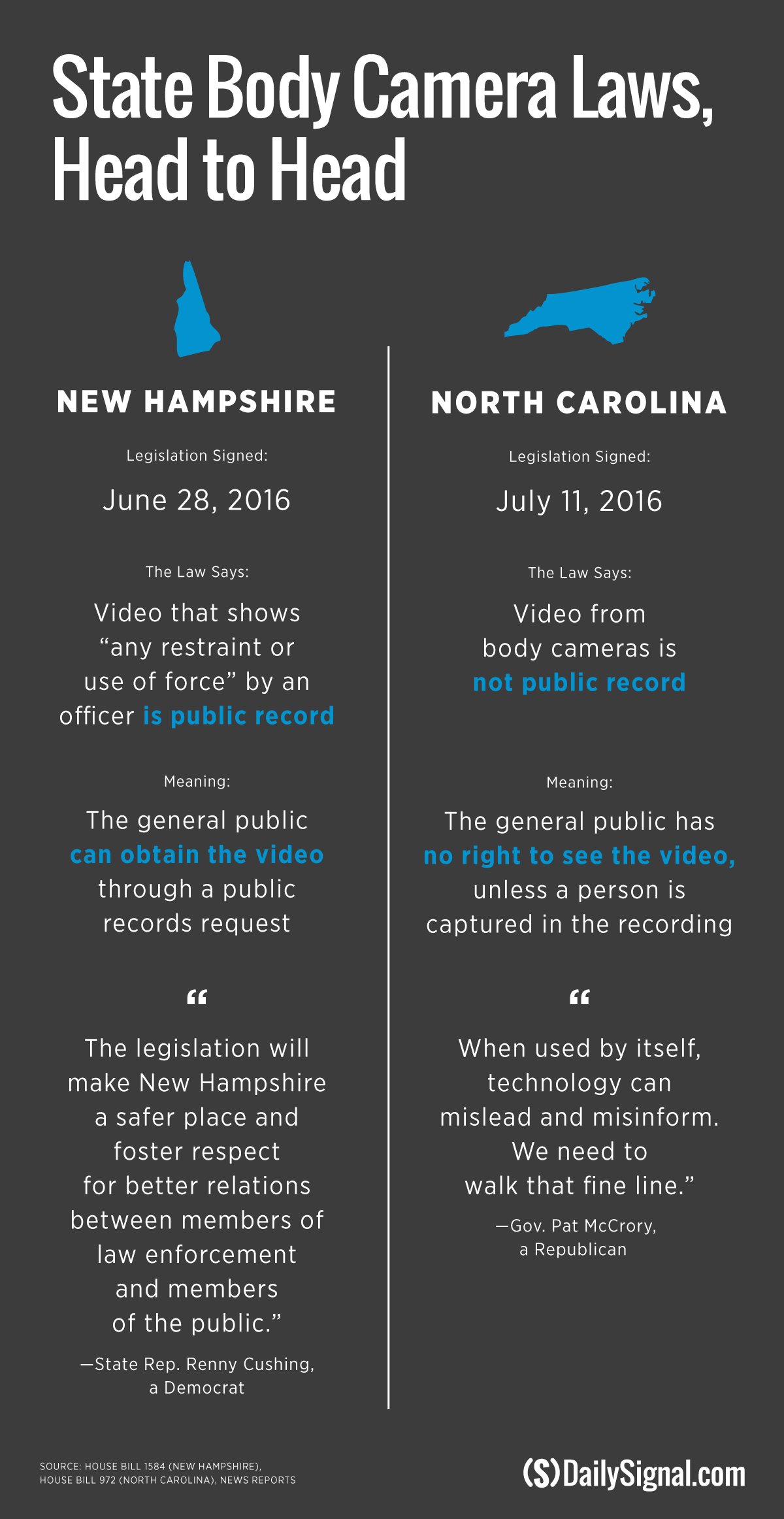

For example, this month, North Carolina Gov. Pat McCrory, a Republican, signed into law a policy that says police dashboard camera and body camera footage are not public records.

That means the general public has no right to see or receive copies of the film. People who are seen or heard in the video can request to obtain it.

In June of this year, New Hampshire adopted a body camera law that takes a much different approach.

This policy gives police departments discretion with who can access the footage, allowing video that shows “any restraint or use of force” by an officer to be a part of public record.

In addition, New Hampshire police departments are required to keep footage depicting officer use of force incidents, and citizen complaints, for at least three years.

Marlow of the ACLU contends that while most body camera video holds “no value” and should not be released, especially footage shot in a private residence or that involving confidential informants, material of high public interest should be easy to obtain.

“There is broad consensus in the year 2016 that body cameras are going to be a part of modern policing,” Marlow said. “But there are many people out there whose approach is if the body camera train has left the station, then we can stop the train at its next stop and that is making the video available to the public.”

“If police body cameras are used in the field, but the public does not have the right to see important footage, they go from a tool promoting transparency into becoming yet another police surveillance tool,” Marlow added.

Unique Approach

The New Orleans Police Department has devised a unique process to decide when to release body camera video.

In February, the department created a “critical incident team” that will review body camera footage of every officer-involved incident resulting in serious injury or death, and determine whether to release the video before an investigation of the case is adjudicated.

The team, made up of the department’s deputy chief of internal affairs, the New Orleans city district attorney, the Orleans Parish district attorney, and the U.S attorney for the Eastern District of Louisiana, has one week to make a recommendation on whether to release video.

New Orleans Police Superintendent Michael Harrison then has two additional days to make the final decision.

Harrison, in an interview with The Daily Signal, said there have not yet been any “critical incidents” for the team to review since the policy was created.

In March, the department released body camera video for the first time, documenting two fatal police shootings from the year before. But the release of that video came after the police department’s internal investigation of both shootings found them to be justified. Prosecutors chose not to pursue criminal charges against the officers involved.

Harrison insists that in the future, he would authorize the release of video before a case is settled, even if it shows his officers behaving improperly.

“As chief, I have to think about the shock to the conscience of the community, I have to think about whether showing this video comprises the investigation and I have to worry about public unrest as a result of showing it compared to not showing it,” Harrison told The Daily Signal. “Let’s just be real—sometimes releasing it very well could hurt us more, and that’s okay. If it’s a good video that depicts what happened I would probably show it.”

In addition to creating a robust policy around releasing video, Harrison says a body camera program’s effectiveness is also determined by whether departments hold officers accountable when they don’t follow the rules.

New Orleans began deploying body cameras in April 2014. Today, 620 officers wear them on their chests, including police doing patrols, gang investigations, and even school resource officers.

The department’s policy requires officers to activate the cameras during all calls for service, and if they don’t, Harrison says they could be punished.

“The oversight of the program has to be really good in order to go to the public and say body cameras are a new measure of accountability,” Harrison said.

Supervisors run audits on the video shot by officers every month, reviewing all footage capturing use of force, and also conducting random spot checks.

In April, the department reported that 99 percent of officers were compliant with the rules of the program.

Despite officer buy-in from the program, Harrison is careful about predicting body cameras as the solution to bring police and communities closer together.

“Chiefs should be very careful about giving false expectations that the camera captures everything because it does not,” Harrison said. “It captures what it’s designed to capture, but not 360 degrees.”

“I think New Orleans is doing much better than we have in past with community relations, but we realize there is long way to go,” Harrison added. “But because we are truly transparent, we are given the benefit of the doubt many times. Citizens are feeling better about us, and officers feel better about their department.”