Nearly one year after Kate Steinle was killed in San Francisco allegedly by a man living in the U.S. illegally, the city has approved a new policy restricting the circumstances under which it will cooperate with immigration requests from the federal government.

San Francisco’s new sheriff, Vicki Hennessy, and the city’s board of supervisors reached an agreement last week on legislation that bars law enforcement officials from notifying Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials when they will release a person from custody, except under limited conditions.

The death of Steinle, 32, in July 2015 and the arrest of Juan Francisco Lopez-Sanchez—a repeat drug offender from Mexico with multiple deportations—sparked a national conversation about local jurisdictions that have so-called “sanctuary” policies limiting their cooperation with federal immigration requests.

The sheriff at the time of Steinle’s death, Ross Mirkarimi, carried out a policy that barred communication with federal immigration officials in virtually all circumstances.

Hennessy denied Mirkarimi re-election in November when she ran on a promise that she would increase collaboration between San Francisco law enforcement and ICE.

“San Francisco has crafted a policy that enhances public safety, promotes family unity, and brings communities together,” said Hennessy’s chief of staff, Eileen Hirst, in an interview with The Daily Signal.

Hirst says of the roughly 45 requests from ICE this year to be notified of the release of defendants from custody, Hennessy—who has been reviewing each case herself until the new policy is implemented—has agreed to none of them.

Under the new policy, the sheriff’s department will fulfill ICE requests to be notified of the release of suspected illegal immigrants only when the defendant is charged with a serious or violent felony, and a judge has determined there is probable cause to believe the person is guilty.

In addition, for the sheriff to share release information with ICE, the defendant must have previous criminal convictions.

Specifically, the sheriff will notify ICE of an impending release if the person either has been convicted of a violent felony within the last seven years; convicted of a serious felony in the previous five years; or convicted of three serious or violent felonies within the previous 10 years.

Even after the sheriff determines a case meets these conditions, Hennessy can still decide not to honor ICE’s request by considering “mitigating factors” such as the person’s ties to the community and whether they’ve attempted to rehabilitate themselves.

Hirst said if the new policy were in place last year, San Francisco still wouldn’t have handed over information about Lopez-Sanchez because his previous felonies were not considered serious.

Immigration advocates argue San Francisco’s new policy is an improvement over the previous one. They say San Francisco’s experience showcases the success of the Obama administration’s revised immigration enforcement program, called the Priority Enforcement Program.

In Nov. 2014, President Barack Obama, as part of his executive actions on immigration, issued a directive to end a controversial program called Secure Communities that required local law enforcement to hold illegal immigrants they arrested for deportation, even without probable cause.

The program, created in 2008 under President George W. Bush and expanded by Obama, was criticized for punishing immigrants arrested for less serious crimes, like minor traffic violations.

With the Priority Enforcement Program, local authorities are supposed to notify ICE only when they plan to release someone federal officials have requested information on.

ICE, however, can still issue a detainer if it believes it has probable cause to deport an illegal immigrant who has been arrested, even if they haven’t been convicted.

Because of a 2014 federal appeals court ruling, which said that complying with detainer requests is optional, local jurisdictions are legally free to enact their own immigration policies.

Federal immigration officials say that the program promotes even more local control, and that as a result, many agencies who had not been willing to work with the federal government are now cooperating in some way.

“A certain amount of local control over these issues is perfectly reasonable,” Alex Nowrasteh, an immigration policy analyst at the Cato Institute, said in an interview with The Daily Signal.

“PEP is much better than the all or nothing approach from before it,” Nowrasteh continued. “It allows for a just middle ground. If the budget only allows for deporting a few thousand people per year, I would hope the focus would be concentrated on actually violent and property criminals, not just people who committed minor infractions and ended up in local detention because of it.”

But critics say the implementation of the Priority Enforcement Program encourages so-called sanctuary cities to keep their policies the way they are.

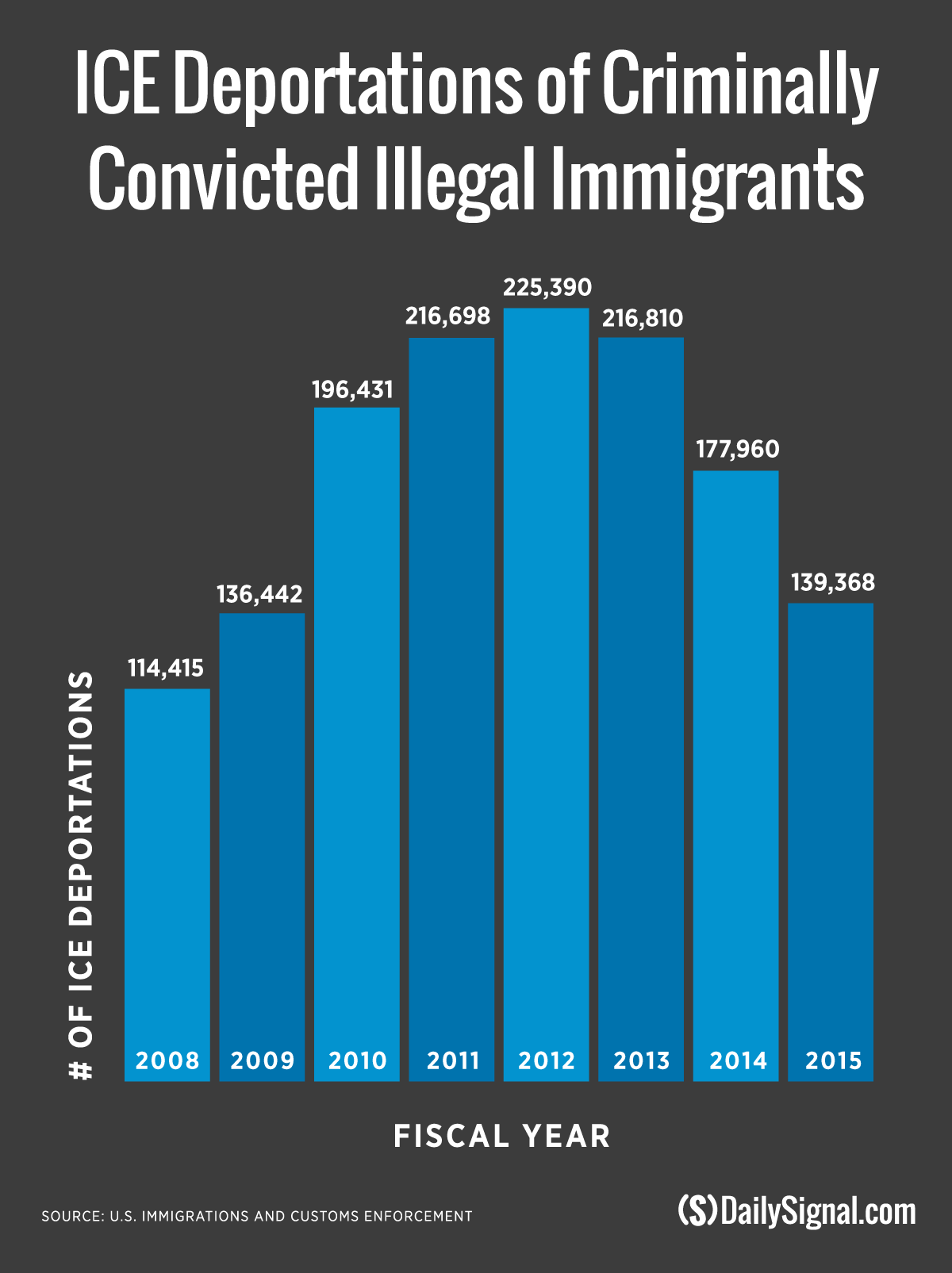

Jessica Vaughan of the Center for Immigration Studies notes that ICE has been deporting fewer criminally convicted illegal immigrants lately.

According to ICE statistics, the agency deported 139,368 criminally convicted illegal immigrants in 2015, compared to 177,960 in 2014.

Along with implementing the Priority Enforcement Program, the Obama administration has also narrowed the focus of who it seeks to deport by prioritizing its resources on three different categories of people.

- Illegal immigrants deemed threats to national security or public safety

- Those who have been convicted of multiple significant misdemeanors

- And recent border-crossers who have been ordered removed on or after Jan. 1, 2014.

“I don’t see evidence that PEP is doing a better job of removing criminal aliens,” Vaughan told The Daily Signal. “The sanctuary cities problem is not what is responsible for a decline in deportations. It’s because of the Obama administration’s policies and that they’ve put so many criminal aliens off limits for immigration officers.”

Back in San Francisco, Hirst of the sheriff’s department defends the city’s new legislation, which still must be approved by Mayor Ed Lee before going into effect.

Hirst acknowledges the risk of the policy, but believes it is a healthy middle ground for a city dealing with deep distrust between law enforcement and minority communities.

“We release hundreds of people every year from jail—they may be citizens, they may be immigrants, and they may be undocumented immigrants,” Hirst said. “And we don’t know what they are going to do in the future. Nonetheless, under this amendment to the sanctuary policy, there will be due process for all.”