Obamacare’s 13th co-op announced it’s closing ahead of the 2017 open enrollment period, and more of the nonprofit insurers could follow suit in the coming months.

Ohio’s InHealth Mutual announced late last week it would be closing its doors after the state’s Department of Insurance requested to liquidate the insurer.

As insurers prepare to submit proposed rate changes to the government ahead of the next open enrollment period, it’s likely Ohio’s co-op won’t be the last to close its doors.

“I think there are a couple of reasons why the picture will be clearer later in the summer,” Ed Haislmaier, a Heritage Foundation senior research fellow in health policy, told The Daily Signal. “First, insurers are making decisions to participate in the exchange and submitting rates. The other is the risk adjustment formula will kick in for the last plan year, 2015, this summer.”

“Based on that, some companies may not make it. Some companies may decide to exit,” he continued.

InHealth Mutual enrolled nearly 22,000 consumers, with the majority selecting individual market plans. Customers now have 60 days to select a new plan on the federal exchange.

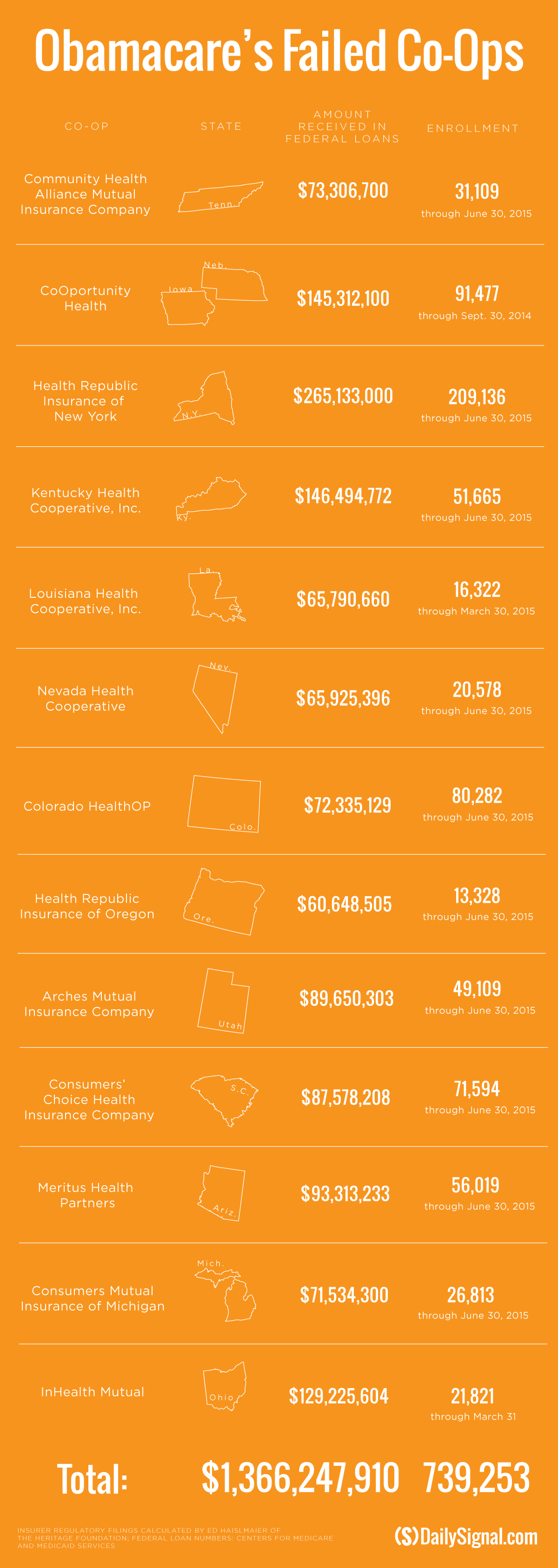

Ohio’s co-op, or consumer operated and oriented plan, is the 13th co-op created under the Affordable Care Act to close its doors. Twenty-four co-ops launched in 2013 with a total of $2.4 billion in start up and solvency loans awarded by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

InHealth Mutual received $129.2 million in loans, according to the agency.

Collectively, the now 13 failed co-ops received more than $1.3 billion in loans and enrolled more than 730,000 consumers across the 14 states they served. Those consumers were forced to pick new plans on the exchanges.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has not yet said definitively whether the co-ops will be able to repay the loans received. However, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Acting Administrator Andy Slavitt told a congressional panel his agency is working with the Justice Department to recoup the money.

Many of the co-ops that closed their doors did so late last year and cited Obamacare’s risk corridor program as their reason for doing so.

Under the risk corridor program, insurers requesting money from it received just 12.6 percent of the total amount they each asked the government for. InHealth Mutual expected to receive $47 million from the risk corridor program, according to court filings.

Though the risk corridor program damaged the long-term viability of nearly half of the co-ops, Haislmaier said it’s likely Obamacare’s risk adjustment program could have a significant impact on the remaining 11 co-ops’ futures.

Under Obamacare’s risk adjustment program, money is transferred from insurers that enroll lower-risk populations to those that enroll higher-risk populations.

“The risk adjustment program is the one that seems to be damaging to small insurers, particularly co-ops,” Haislmaier said. “There’s a big problem with the risk adjustment program being erroneous, and it’s disproportionately hitting smaller insurers.”

Haislmaier said the Department of Health and Human Services is “trying to say it’s working, but the data is showing it’s much worse” than the Obama administration is letting on.

According to InHealth Mutual’s order of liquidation, issued May 26, the company paid $3.4 million to the government under the risk adjustment program, which hurt the nonprofit.

Additionally, two other smaller insurers not selling coverage on Obamacare’s exchanges—Health Plan Select in Georgia and Family Health Hawaii—announced their respective decisions to close.

According to The Oconee Enterprise, officials with Health Plan Select decided to close “rather than pay a surcharge into the federal exchange.”

Because Health Plan Select wasn’t sold on the exchange, Haislmaier said the surcharge was in reference to payments into the risk adjustment program.

“Smaller insurers have exited the market entirely or closed down—insurers that weren’t even on the exchanges—because they were hit with huge bills for risk adjustment,” he said.

The Department of Health and Human Services doesn’t have to allow all insurers to sell coverage on Obamacare’s exchanges and has in the past evaluated the long-term viability of the co-ops when deciding whether to allow them to participate in the marketplaces.

In November, Mandy Cohen, chief operating officer for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, told lawmakers only co-ops that were financially viable could sell coverage on the exchanges, avoiding “mid-year failure” for customers.

At the state level, insurance commissioners decide whether a co-op should enter into liquidation or not.

Because 13 co-ops have already shuttered, Haislmaier said it’s likely insurance commissioners are following the nonprofit insurers “more diligently.”

“The experience with the co-ops has probably made them heighten scrutiny a bit because I think the experience so far, there have already been a couple plans that have been shut down and liquidated as of May 6,” he said, referencing Hawaii and Georgia’s smaller insurers. “This is the kind of thing that’s going on under the radar.”