HOUSTON—Like most millennials, the 25-year-old Muslim man giving the evening sermon at the Madrasah Islamiah mosque in Houston is obsessed with getting the word out.

Each sermon delivered by Mufti Mohammed Wasim Khan represents a different verse of the Quran, so the audience can look forward to something new.

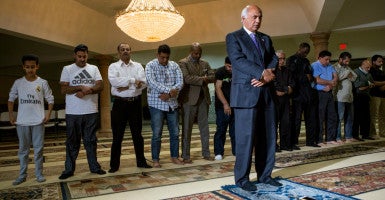

As the mosque fills up for the evening prayers with Arabs, South Asians, Latinos, blacks and whites, new Texas immigrants, and American lifers, Wasim Khan props his iPhone onto a tripod and sends his message to the world.

“We stand in solidarity with everyone who has been oppressed,” Wasim Khan says, recognizing the victims of the Brussels attacks a day earlier, but also less-publicized acts of terrorism in the Muslim-majority countries of Turkey, Yemen, and Indonesia.

“What unites us is love and compassion amongst one another,” he concludes.

>>> Second of two parts: How These American Muslims Seek to Keep Their Country Safe

>>> Read Part One: Houston’s Muslim-Led Plan to Protect the Homeland

“We address every single atrocity that takes place,” Wasim Khan tells The Daily Signal after the sermon, referring to the mosque. “When people ask if we address terrorism, they are questioning our humanity, not our religiosity.”

In December 2014, two leaders of Houston’s Muslim community, Mustafa Tameez and Wardah Khalid, created a plan meant to protect the region’s Muslims against the threat of radicalization, and to meet other challenges.

The plan is one of about 10 community-based programs across the country that bring together religious figures, law enforcement, mental health providers, educators, and social services to help prevent Muslims, and others, from becoming radicalized.

Over three days in Houston late last month, The Daily Signal met and spoke with Muslim community leaders, and everyday people, about what their religion means to them, how they live their lives as Americans, and what should be expected of them, if anything, to counter extremism.

The message from Muslims like Wasim Khan was unanimous: Houston—where leaders boast of its being the nation’s most diverse city, with the largest Muslim population in the South and more than 100 mosques—is a showcase for how ordinary American Muslims and initiatives to counter extremism can coexist.

The Scholar

Born in Dallas and raised in New Jersey, Wasim Khan—who is of Indian, Afghani, Pakistani, Syrian, and Iraqi descent—is passionate about telling the story of Islam the way he says it’s supposed to be told.

And he tells this tale through today’s platforms, posting the videos of his sermons on his YouTube and Facebook pages, and on his Twitter account.

“Why am I on the Internet?” Wasim Khan asks, then answers:

Because I am a millennial. My whole life relies on Facebook and Snapchat and Twitter. This is my life. I am born in 1990. I am definitely consciously doing it because I believe in transparency. I believe that if anyone wants to come and listen to our program, they are allowed to. I have nothing to hide over here.

Mufti Mohammed Wasim Khan, a Muslim scholar and Houston resident, broadcasts his sermons over YouTube to make them accessible to the public. (Photo: Scott Dalton for The Daily Signal)

Wasim Khan began studying Islamic science at 13 years old, and has studied the Quran on four continents.

He says he’s the youngest mufti—a certified expert on Islamic law—from the state of New Jersey. He travels the country delivering sermons, interpreting one verse after another, in order.

Because it’s not enough to keep the knowledge to himself.

“People become radicalized because they don’t go to the mosque to learn about how to interpret the Quran,” Wasim Khan says. “The terrorists pick select verses and exploit them to fit their agenda. Here, in the mosque, we interpret every single verse, so our community understands what God is saying to us.”

Wasim Khan is also active in his community beyond the Islamic religious space. On the side, he serves as a volunteer chaplain to inmates in New Jersey prisons. He says he reads the Bible and the Torah.

Children at Madrasah Islamiah mosque in Houston are taught to learn the Quran in its full context. (Photo: Scott Dalton for The Daily Signal)

He’s a Bernie Sanders supporter and belongs to a nonprofit group called Houston Millennials, where people of different faiths, races, and backgrounds come together to inspire entrepreneurism and volunteerism.

“What bring us together is we want to make a difference in our generation,” Wasim Khan says. “I promote this idea in my community that we can’t be selfish, and that’s inspired by my faith.”

Though he is younger than many of the mosque attendees listening to his sermons, Wasim Khan seems to attract respect.

As he wound down in his office after the sermon, an older man who just moved to Houston from Iraq as a refugee approached Wasim Khan to give him a cup of tea to soothe his throat.

“God protect America,” the man says.

Wasim Khan is doing his part, and he has the credentials to do it.

“These terrorists want to adulterate the very fabric of what makes our country great and what made our country where it is today—our tolerance—and if they accomplish that, then we have lost,” Wasim Khan says. “Their biggest enemies are the ones who can ultimately stop what they are saying and doing, the only ones—fellow Muslims. If I stand up to them or someone else from my community stands up, we can academically prove that they are wrong.”

The Administrator

In some ways, Houston’s Muslim community is uniquely set up to effectively carry out its own counterterrorism plan.

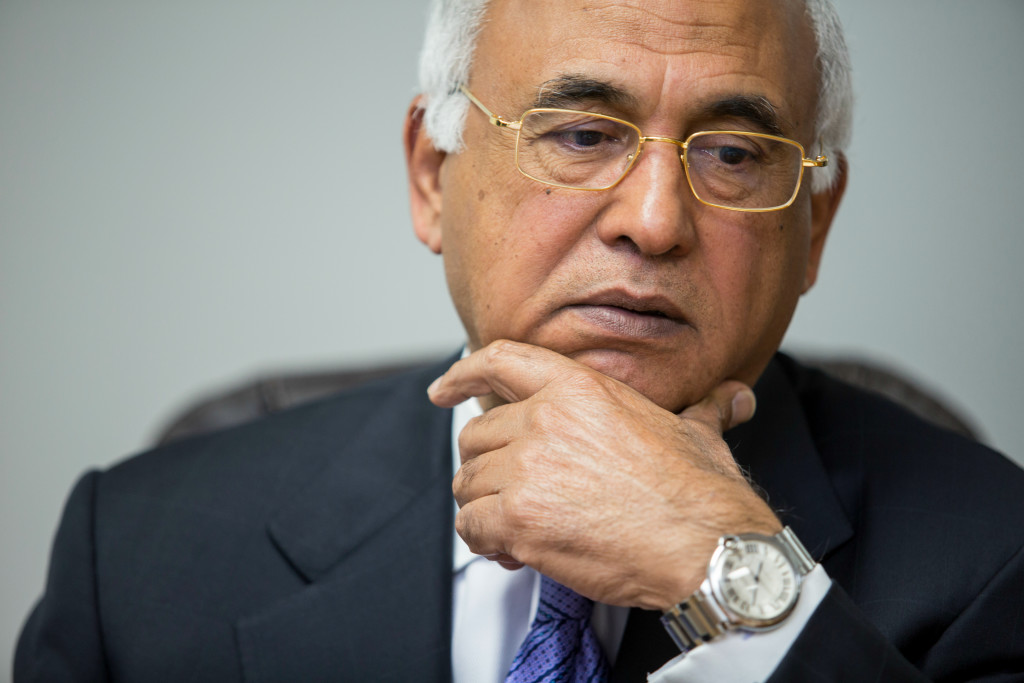

Houston’s mosques are governed under an umbrella organization, the Islamic Society of Greater Houston, which calls itself the largest Muslim organization in America.

The organization, created in 1969, has an elected president and board of directors, and allows for continuity in how mosques are run.

M. J. Khan, president of the Islamic Society of Greater Houston, says he maintains a “zero tolerance” policy against extremism in mosques governed by his organization. (Photo: Scott Dalton for The Daily Signal)

The Islamic Society of Greater Houston divides the city into five zones, so that each segment of the city has a mosque nearby.

Each zone has its own board that includes people elected from that specific geographical area. They are empowered to run their mosques as they wish, while still having to report to the larger board of directors and the president.

Not all of Houston’s mosques belong to the Islamic Society, however, so other groups are free to build their own mosque without being a part of the larger organization. Though the Islamic Society does not discriminate against any particular sect of Islam, most of its mosques are run and attended by adherents of the Sunni Muslim faith.

The organization’s leaders do not tell imams of individual mosques how to give their sermons, and have no input into their content. However, the organization promotes a “zero tolerance” policy against extremism and directs how mosque congregants should report radical activity or rhetoric if they encounter it.

M.J. Khan, current president of the Islamic Society of Greater Houston, initiated the policy. When he launched it, Khan says, he told imams to announce the policy after their sermons, so no one could say they didn’t know.

“We have come up with a policy where we constantly engage our young people, teach them the proper teaching of Islam, and keep them occupied, because we don’t want to lose a single person to extremism,” Khan says.

“Our structure keeps the community united and cohesive, and helps the organization have communication and interaction with both the Muslim community and with the members of other faiths.”

Khan’s post as the group’s president is full time. A former real estate developer and gas station owner, he also was the first Muslim member of the Houston City Council, serving three terms.

If Khan and the Islamic Society’s board of directors were to learn of extremist behavior at one of the group’s mosques, and the imam or local administrator did not report it, he says, the leadership of that mosque could be suspended or removed from his position or have spending authorities revoked.

The Islamic Society of Greater Houston expects scholars at its mosques to adhere to “proper teaching.” (Photo: Scott Dalton for The Daily Signal)

Khan says he regularly meets with representatives from the FBI and the local sheriff’s office and police department, and that religious leaders, administrators, and members of mosques are encouraged to contact law enforcement about suspicious activity even before they alert his organization.

The Islamic Society’s “see something, say something” policy recently played out in a real way, when a 19-year-old from the nearby town of Spring, Texas, was arrested for trying to join ISIS.

In May 2015, the FBI charged Asher Abid Khan with conspiracy and attempting to provide material support for ISIS. He faces up to 30 years in prison.

After the arrest, M.J. Khan (no relation) received an email and phone call from an imam at the mosque where Abid Khan had prayed and taught religious studies, warning that the young man had communicated potentially extremist views on his Facebook page.

That mosque, Masjid Al Salam, belongs to the Islamic Society of Greater Houston.

The FBI had been surveilling Abid Khan in October 2014, according to The Washington Post, and became aware of his plans to join ISIS because of his communications through social media with a friend who ultimately made it to Syria to fight for the terrorist group.

Abid Khan traveled to Turkey with plans to go on to Syria, but never made it there. He was tricked into coming home to Houston by his family, and soon arrested.

“He got arrested before we could do anything,” M.J. Khan says. “The imam did the right thing and contacted me. But he did not contact me as early as he should have.”

Khan says the Islamic Society’s board voted to suspend the director of the zone that includes Masjid Al Salam for a month, “because we felt he knew about the situation like the imam did” but he didn’t act.

This was the first and only time the Islamic Society received a report related to extremism since he became president in January 2015, Khan says.

While Khan’s job is administrative, and he doesn’t have the religious training of an imam, he is a practicing Muslim who taught his own children about the proper teachings of Islam as well as life lessons such as staying away from drugs and gangs, and maintaining strong ethics.

“I am not a scholar and you don’t have to be a scholar,” he says, adding:

There are commonsense things we teach our kids. The family is the most effective communicator of those lessons—before the teacher, before the imam, and before the president of the Islamic Society of Greater Houston. It’s the family’s responsibility primarily, so we encourage them to have open communications with their kids and also to know who they are interacting with.

Many Muslim parents value open communication with their children about faith. (Photo: Scott Dalton for The Daily Signal)

Khan says he sometimes believes there’s an expectation for Muslims, and especially a leader like himself, to take that communication outside the house and publicly condemn every extremist act—to reassure non-Muslims about the peacefulness of their faith.

He says most immigrant communities, especially those of first-generation immigrants like himself, tend to be insular and this may explain the perception among some that Muslims aren’t doing enough.

But he also thinks the characterization isn’t entirely fair:

The area where we have primary responsibility is our community and our kids and our woman and our man to make sure that everybody is clear what the Islamic teachings are, and what our responsibilities are as human beings, as citizens, and as neighbors. That’s our responsibility. But with that said, we have to do more outreach. When we don’t do that, people don’t know about you. We suffer from that a lot.

Just after sunset on a Wednesday in late March, Khan walks from his office wearing a business suit into an attached mosque, the River Oaks Islamic Center.

It was the fourth prayer of the day and not only will he not miss it, he will lead it.

The tradition of the Sunni Muslim faith says that anybody can lead regular prayers when the imam is not present. Usually, whoever attends at that time (about 20 or so were at this gathering) selects the person “best among them” or someone who is familiar with the Quran.

In Sunni Islam, “there is no hierarchy,” Khan says, so someone cannot designate him or herself as the leader—the person must be chosen.

After some negotiation, the group picks Khan to lead the prayer, though many do not know he is president of the Islamic Society. Khan pulls a blue prayer mat in front of the line of worshipers behind him, kneels down, and reads the prayer from his iPhone.

Standing shoulder to shoulder, those gathered—some wearing hoodie sweatshirts, backward ball caps and jeans, others in traditional Islamic garb, all without shoes—follow his lead.

The prayer lasts for seven minutes, and Khan heads back to work.

On his way back to his office, he stops to talk with Nashwa Khalil, a young woman of Egyptian descent who was born in California. A researcher at a hospital, she plans to open a coffee shop inside the mosque where Khan had just prayed.

Khalil calls herself as “American as apple pie,” but she thinks local Muslims can do a better job of communicating what they stand for:

I mean, Muslims literally invented coffee. This idea that mosques and Muslims are closed—it’s not true. But maybe we need to make it more obvious. So why not please come in and have a cup of coffee? To associate normal things with Muslims—that coffee is something we are good at that we created and you drink everyday—is valuable.

The Uniter

Shazad Bashir, a 58-year-old Muslim who’s had a lifetime of success stories, wants to leave no doubt about where his community stands.

Bashir is a self-made businessman and philanthropist from Pakistan who goes hunting on weekends and is so confident in his Americanism that he says he doesn’t care—he uses a more colorful phrase—how American you think he is.

He doesn’t mean this in a demeaning way. Bashir says he believes the best way for Muslims to counter the radical message is to act out the lessons they know their religion to represent. And he’s been doing that his whole life.

“I can’t even think how these son of a b—— even call themselves Muslims when they have broken the basic tenet of Islam, as in other Abrahamic religions, about respecting life,” says Bashir, who repeatedly excuses himself for swearing. “That’s the primary purpose of Muslims: to help other people. That’s how Muslims live their life.”

Shazad Bashir, a Houston businessman, aims to launch a Muslim version of the Jewish Federation of Greater Houston to foster understanding. (Photo: Scott Dalton for The Daily Signal)

Bashir, a Houston resident since 1998, is president of the Shifa Clinic, a nonprofit health care and social services provider he founded with fellow Muslims. The clinic, which has several locations across Houston and Harris County, provides free general medical services, dental care, and assistance for abused women. Its 65 volunteer health professionals serve clients of any religion, not just Muslims.

Tameez and Khalid’s plan to counter violent extremism cites the Shifa Clinic as an already-existing service that can be leveraged to fulfill other needs in the Muslim community, including mental health care. Though the clinic does provide psychiatric care, Tameez, 46, and Khalid, 29, believe Shifa can bolster its capacity by providing volunteer social work and substance abuse treatment.

Bashir also leads an effort to create what he calls the Muslim version of the Jewish Federation of Greater Houston. (He says he’d even like to hire a Jewish CEO.)

This organization would serve as a hub that would collect donations and direct the money to all the various organizations serving Muslims.

Bashir says such a high-profile project would provide panache and credibility that could cut across the broader community.

“The No. 1 goal, perhaps the only goal, is to make sure Muslim Americans are understood,” Bashir says. “Quite honestly, my view is that being a Muslim doesn’t make you less American. And being an American doesn’t make you less Muslim. It is totally compatible.”

The deadly terrorist attacks in Belgium occur earlier the same day Bashir discusses his hopes for a counternarrative, threatening to disrupt the story. Bashir spends the morning texting his siblings in a group chat. One thing that never comes up in the conversation: religion.

“I got up this morning with shock and horror when I heard about Brussels, and reacted like a pure American,” Bashir says, explaining:

It has nothing to do with religion. Honestly, that possibility is not even on my radar. I go and pray at the mosque and the people I meet are people who talk about the Final Four. I go to my ranch on weekends, and I am worried about what protein feed we need to feed the deer. I can’t be expected to put every idiot’s issue on my shoulder. Maybe I should be more worried. But I don’t see any reason why.

So Bashir will continue to show the best way forward through action, and hope people get the message.

“At the end of the day, actions speak louder than words—what we are, what we stand for, how we deal with neighbors, friends, and colleagues,” Bashir says. “As a Muslim, I get up every morning and think, ‘Did I make a difference yesterday in someone’s life?’ That is what Islam is all about.”

The Healer

For Muslims in the Houston area who are not as comfortable living out their religion in America, or are unsure how to do it, or if they even want to, Sadia Jalali is the person there to help them reconcile their identity.

Jalali is not a therapist for Muslims. She doesn’t bring religion into the room unless someone puts it there. But as a Houston-based marriage and family therapist, she says, recognizes Muslim Americans face unique challenges, especially the youth:

A lot of the kids I see have second-generation issues. Their parents are immigrants who usually grew up in pretty conservative dynamics and they are trying to raise kids the way they were raised. But raising your kid in America as opposed to somewhere else is really different. Some of these kids are barely Muslim, while their parents are practicing the faith. So I try to get parents to understand the struggles and challenges of keeping a Muslim identity here and what that looks like and how to balance that with having an American identity.

Sadia Jalali, a Houston-based therapist, says her urge to help people is “directly rooted” in her Muslim faith. (Photo: Scott Dalton for The Daily Signal)

Born in Miami and raised in Houston, Jalali, 36, figures that balance every day in how she raises her four children, who range in age from 4 to 10.

She chose to have her children educated in an Islamic school to keep them rooted in their heritage. But she chose a school that prioritizes connecting with other groups, where the students do charity projects such as serving the homeless and reading to seniors.

“I also made it a point to put them in swimming, or soccer, or gymnastics, where they could be around non-Muslims, because you don’t want them to be in a bubble,” Jalali says.

That exposure may not be enough, though. In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks in San Bernardino, Calif., Jalali says she’s concerned about political rhetoric that she sees as anti-Muslim. And she’s worried that this message is reaching the general public.

Her younger clients have expressed more anxiety lately about their place in America, Jalali says:

I get really frustrated. It’s like that double-sided thing where on one hand [it’s] listen, we can’t dig our heads in the sand, there is something going on, whether rare or not, so let’s address that. But overall, it’s like, we’re tired. We’re kind of tired of being held responsible for something we had absolutely nothing to do with.

I don’t know how much we need to condemn. It’s obvious no one in the Muslim community is OK with any of this [terrorism]. It’s utterly awful and it guts us like it guts any other American. I shouldn’t have a guilty conscience about anything. Having a collective guilty conscience is very weird, and I don’t know why people feel Muslims should have that.

Tameez and Khalid, the authors of Houston’s plan to counter violent extremism, are both of Pakistani descent. They interviewed Jalali as part of their report.

In it, they noted that young Muslims who don’t feel rooted in their community are especially at risk for being attracted by terrorist groups, “because [such groups] provide them purpose and a perceived opportunity to create change on behalf of Islam.”

Young people are often hesitant to seek help for mental health issues, according to the report, and Tameez and Khalid recommend providers offer counseling services in familiar places such as mosques and schools.

Jalali says she believes Houston is woefully short of mental health providers, and because she runs a private practice clinic, it requires more effort for people to find her.

She says she has never seen a patient who has showed signs of being attracted to radicalism, but if she did serve such a person, she would know how to handle it:

What I’ve always told my kids is they [terrorists] are criminals. It’s a criminal act and it has nothing to do with our faith. I try to get them to understand even if they try to claim this is a religious issue, you should go back to the sources, read the text, and you’ll feel a lot better.

And then you have to have the geopolitical conversation; some of these groups have agendas. And it’s power. I pick at it from multiple levels of how flawed the logic is. We’ve got to keep people connected. It’s when people feel disconnected that that stuff pulls at them. That idea of belonging, that sense of purpose, is what these recruiters are really good at now.

Jalali knows her purpose—helping people—and she’s confident this principle folds perfectly into her faith.

“Every day I try to do right by people—that’s my job,” Jalali says. “I literally try to make people feel better around me. That very much is directly rooted in my faith.”

The Settler

Houston’s reputation as a place where Muslims, and other minority groups, feel comfortable living has naturally made it a destination for a more vulnerable population: the uprooted.

Last year, Houston welcomed 1,869 refugees, taking in more of them than every other city in the U.S.

Ghulam Kehar, a Los Angeles-born young professional, spends his days settling refugees, welcoming them in an office full of Houston sports memorabilia with a warning: “Be careful.”

Ghulam Kehar runs a nonprofit to help refugees, most of them Muslim, settle in Houston. (Photo: Scott Dalton for The Daily Signal)

That advice has become necessary as some refugees are expressing fear upon arriving in Houston, Kehar says, due to recent political rhetoric and actions that they view as discriminatory against refugees and immigrants, particularly Muslims.

“We are having these conversations with the [refugee] families,” says Kehar, who is the chief executive officer of Amaanah Refugee Services. “We are saying be careful with your kids, don’t go out late at night because you are wearing a headscarf. Make sure someone is with you. They came here for peace and this [suspicion] is what they are experiencing. It’s like they are reliving what they escaped. It’s really horrible.”

In December, Texas officials filed suit against the federal government in an attempt to block Syrian refugees from being settled in the state.

At the national level, Republicans in Congress have proposed making it more difficult for refugees from Syria, Iraq, and other war-torn areas to settle in the U.S., for fear that ISIS will infiltrate the process.

It didn’t help matters earlier this year when a 24-year-old Houstonian and Iraqi refugee, Faraj Saeed Al Hardan, was arrested and charged with providing material support to a foreign terrorist organization (ISIS).

Hardan had entered the U.S. in 2009, and he was granted legal permanent resident status in 2011. M.J. Khan of the Islamic Society of Greater Houston says his organization has no record of Hardan having attended one of their mosques.

As the scrutiny of refugees has increased recently, Kehar says Amaanah has experienced an uptick in volunteers.

Amaanah has a crucial role to play in ensuring refugees transition smoothly to America—and guarding against the rare chance that one takes the wrong path.

When refugees come to Houston, their first point of contact is one of five federally funded resettlement agencies. Amaanah is not one of those.

The resettlement agencies provide government assistance during the refugees’ first three to six months in the U.S., including cash to cover basic needs such as housing, food, and medical care.

And then they are on their own. That’s where Amaanah Refugee Services steps in.

“The challenge comes after the government assistance ends,” Kehar says. “There is not much support for them, and that’s not enough time for them to stand on their own two feet. So our whole focus is the post-resettlement period. Our mission is to assist them with long-term integration into their homes and communities.”

Amannah, a nonprofit funded through private donations—mostly from Muslims—provides after-school programming for refugee children, including academic support and field trips. It also provides direct financial support to help pay for refugees’ rent after the resettlement agencies’ assistance ceases.

In addition, Amaanah helps refugees land jobs, and it gives them free food, furniture, and household items. And Amannah devotes special attention to single mothers. Amannah usually maintains services for refugees for about a year. Kehar says:

You hear resettlement agencies say 90 percent of refugees are self-sufficient after the six-month period. The federal definition of self-sufficiency is not what you and I would define [as] self-sufficiency. It pretty much means you have a job—that’s it. You could not be meeting your expenses. You could not speak the English language. Or you could not even have a car. But on paper, you are classified as self-sufficient.

While Amaanah doesn’t track the religion of the refugees it serves, Kehar says the majority are Muslim.

Refugees who settle in Houston from Iraq—about 30 percent—represent the largest population. A little over 20 percent come from Myanmar (or Burma) and another 15 percent from the Republic of Congo. Only about 6 percent of refugees last year came to Houston from Syria, Kehar says.

Kehar’s parents are from Pakistan, but he was born and bred in Los Angeles.

He wasn’t raised religious. Kehar says he found Islam independently, and he lives out his faith explicitly.

He visits the mosque across the street before and after work, and sometimes makes it out to pray during lunch.

His faith also underlies his will to help people.

“It’s a very conscious choice,” Kehar says of his decision to embrace Islam:

I have a lot of siblings and family members who are completely the other way. What drives me to do the work here is my faith, just appreciating how much service and genuine care and compassion is embedded in the religion.

Kehar started Amaanah in 2008 after participating in a service project while a student at the University of Houston. Kehar and his friends were assigned to help a Somali refugee family, who packed 14 people into a three-bedroom apartment.

They funded the organization through their personal finances the first year; this year, Amaanah has a donor-funded budget of $1 million. Kehar named the organization to represent the Arabic word, amanah, which translates in English as trustworthiness.

During a great time of need, and under challenging circumstances, Kehar’s service is especially valuable.

“At the end of the day my role is kind of unique because I’m involved with refugee work and the Muslim community,” Kehar says. “From my experience, I can tell you that refugees are very scared right now and trying to figure out what to do. I can’t really change the narrative, but I can live every day as an upright Muslim and interact with people and show them we’re normal and—not only normal—I’d like to show them that we are outstanding in the Muslim community.”

The Settled

Masehullah Sahil, a recent arrival to Houston from Afghanistan, is feeling at home.

Every day, he says, he tries his hardest to make it to prayers at the mosque, but if he can’t, and the demands of school and work and molding into an American become too much, he won’t hesitate to lay his prayer mat down smack in the middle of a parking lot, and maybe he’ll invite his Christian coworkers to watch and learn something.

“Houston is one of the most diverse cities I have seen, so, to be honest, I have never felt weird here about my religious activities,” Sahil says.

Masehullah Sahil and his five children are adjusting to Houston after their relocation from Afghanistan, where he was a translator for the U.S. military. (Photo: Scott Dalton for The Daily Signal)

Adjusting to normal life has been more difficult. Sahil, 29, came to Houston in August 2014 on a special immigrant visa, a status offered to those who worked as a translator with the U.S. armed services in Iraq or Afghanistan.

For more than nine years, Sahil was a peer among different units of the Army in combat zones throughout Afghanistan. That close connection made him an infidel to al-Qaeda and the Taliban, and he feared for his life.

“What I did, I do not regret it,” Sahil says. “I did the right thing. I support the U.S. and I support my country. I still do that, and if they need my help with anything again, I will help them.”

When he came to America, Sahil expected the country he served to give back.

Kehar, from Amaanah Refugee Services, says those with special immigrant visas are served by the resettlement agencies that work with refugees.

So the federal funding provided to special immigrant visa holders is from the same source, but little of that money is set aside specifically to serve them, Kehar says.

Sahil says he and his family—his wife, four children, and a baby born after the family arrived in Houston—didn’t get the full amount of money originally allocated.

He says the mattresses provided were small and flimsy, and the children chose to sleep on the floor of an apartment they could not afford.

The settlement agency that initially assisted Sahil connected him with Amaanah, which provided him better furniture, and helped him pay rent. Today, Sahil volunteers with Amaanah. He speaks five languages, and is one of few recent immigrant arrivals to Houston who can speak fluent English.

“When we were in our country, our expectations were very high for the U.S.,” Sahil says of his family’s life in Afghanistan. “We were thinking we would come here and have no problems, and have everything we need, if we worked hard. That’s not just my expectation, but everyone coming to the USA.”

The resettlement agency did land Sahil a factory job paying $8 per hour, and he recently found a new job in security that pays better. It’s still not enough to pay the bills, and support his large family, so Sahil drives for Uber part time. He also—with financial aid— attends Houston Community College, where he studies international relations.

Masehullah Sahil says his family is comfortable practicing their Muslim faith in Houston, though they face some challenges in other aspects of life. (Photo: Scott Dalton for The Daily Signal)

Under the law, Sahil may apply for citizenship after living five years in the U.S. At that point, Sahil can apply to bring his parents and siblings into the country from Jalalabad in eastern Afghanistan. He says his brother receives direct threats from the Taliban because of Sahil’s affiliation with the U.S. Army.

“I told him I can’t do anything—just be careful and just pray,” Sahil says, adding:

I am really frustrated right now. My parents gave me life, and they raised me, and I can’t help them. I just pray they are still alive until that time [of becoming a citizen] and I can take them out.

In his new life, Sahil doesn’t view terrorism as a threat.

But as someone who has seen terrorism up close, Sahil understands what it represents, and how it could harm his family. He says he won’t run away from confronting it.

“I still have shrapnel in my body from a suicide bomb,” Sahil says. “As a Muslim, it doesn’t matter. As a human, as an American resident, if I see signs of terrorism, I have to stop them. I don’t care who it is. If I see the ideology like that, I would take an action.”

The Community

The Maryam Islamic Center is where faith and function exist together.

The mosque, which looks more like a castle, is located among the high-end houses of Sugar Land, Texas, a city outside Houston known as a center of the energy industry.

It’s after sundown, and children wearing T-shirts and flip-flops are warming up for the final prayer by shooting hoops at the mosque’s outdoor basketball court, as brilliant American and Texas flags flutter beside each other on a nearby street light.

Children play basketball before evening prayer at the Maryam Islamic Center in Sugar Land, Texas. (Photo: Scott Dalton for The Daily Signal)

When the prayer ends, the same children of varying ages will wind down by playing billiards and air hockey in the upstairs game room, which frequently hosts movies and pizza on Friday nights.

“This is upscale,” says Haroon Dosani, a Sugar Land resident and native of Pakistan. A businessman who owns car washes, he helps manage the mosque.

Although the mosque seems overtly American, as if it’s deliberately meant to be accessible, Dosani insists this is what his community wanted.

“We try as much as we can to break the stigma of being Muslim in this country,” Dosani says.

Haroon Dosani, third from left, says he helps lead interfaith events at Maryam Islamic Center to “break the stigma.” (Photo: Scott Dalton for The Daily Signal)

Dosani says the sheriff of Fork Bend County, Republican Troy Nehls, is a frequent impromptu visitor to the mosque just to show support, not to surveil.

Once a month, the Maryam Islamic Center hosts an interfaith event, where Muslims, Christians, Jews, and people of other religions unite to share food and tradition.

The terrorist attacks in Brussels occurred earlier this same morning, but not everybody here at the mosque knows what happened.

Raed Alfaleet has been teaching taekwondo inside the mosque all day, and he has just emerged into the night wearing his uniform.

Alfaleet, 35, immigrated from the Gaza Strip to Houston seven years ago. He came alone, but now he’s married to a white, American-born woman.

Alyssa Alfaleet, left, married Raed Alfaleet and converted to Islam. They teach their two children to be accepting of other religions. (Photo: Scott Dalton for The Daily Signal)

Alfaleet met his wife, Alyssa, through a mutual friend from Israel. They were married at the Presbyterian church in her hometown.

After six months of marriage, Alyssa—the daughter of a Sunday school teacher and a church elder—converted from Christianity to Islam.

“I come from a very religious family and they taught me to use your brain, and be open-minded and very critical of everything you read,” says Alyssa, who wears a hijab.

“I had been hearing a lot of negative stuff about Islam after 9/11,” she recalls, so she started studying the religion on her own, and realized the perceptions were wrong. In the end, she says, “It didn’t even feel like a conversion.”

The two are raising young children, Hamza and Reema, and teaching them to follow whatever religion they want.

When his visitor interrupts Alfaleet’s story to tell him the news of the attacks in Brussels, for which ISIS claimed credit, he reacts with outrage and sadness.

His voice lowers, he holds his wife’s hand, and he corrals his daughter into his arms, a man leaning on his family after tragedy.

“If the government of the United States asked me to fight ISIS, absolutely I am the first one to go and get rid of these people,” Alfaleet says.

“I do like this country. I would like to support it in whatever way I can because I am a part of it. My wife is American. My children are half American and Palestinian. We have a very nice life, and I would love the same life for the whole world. Why not?”

Earlier: Meet some of the other people behind Muslim-led plans to protect the homeland.