Two weeks ago the Supreme Court asked both sides in the Little Sisters’ case to file supplemental briefs. The Little Sisters’ case challenged Obamacare’s requirement that nonprofit employers must provide employee health insurance coverage that includes potentially life-ending drugs and devices.

Now the briefs are in—and while the Little Sisters of the Poor and other challengers provided suggestions for other ways the government could advance its interest in making sure women receive contraceptive coverage—the government doubled-down and argued that its existing “accommodation” already fits the bill.

A Religious Objection to Providing Life Ending Drugs

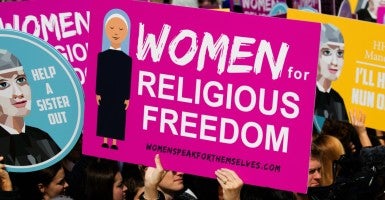

Many employers, such as the Little Sisters of the Poor, Priests for Life, and religious colleges and charities, object to including contraception and potentially life-ending drugs and devices in their health insurance plans.

Under the current regulations (which the government refers to as an “accommodation”), employers must either submit a self-certification form to their insurer or health plan administrator or notify the Department of Health and Human Services of their religious objection to providing such coverage in writing and provide contact information for their health plan insurer or third-party administrator.

Either way, the actions taken by the employer will authorize the inclusion of coverage of the objectionable drugs and devices in its health plan. The Little Sisters of the Poor and other challengers believe that forcing them to engage in such conduct that will trigger morally objectionable health care coverage makes them complicit, and that imposes a substantial burden on the free exercise of their religious beliefs.

The Supreme Court asked the parties to address how employees would obtain contraceptive coverage through their employer’s insurance companies without any involvement from the employer, including notifying the government, their insurer, or a third-party administrator of their objection.

The Little Sisters of the Poor and other challengers suggest that the government could require insurance providers to make separate contraceptive plans available to employees whose employer plans do not include such coverage. This would require a separate enrollment process along the lines of how some employers have separate dental, vision, or prescription plans, as well as separate “insurance cards, payment sources, and communication streams.”

They maintain that such “truly independent efforts to provide contraceptive coverage to their employees” would allay their religious objections because they would be removed from the process entirely.

The challengers also propose that the government could offer plans on the Obamacare exchanges, contract with commercial insurance companies to provide contraceptive coverage for those who don’t receive it through their employer, or make contraceptives available for free through Title X (a federal grant for family planning).

Government Argues for ‘Minimally Intrusive’ Regulation

In its supplemental brief, the government insists that, aside from the “minimally intrusive” self-certification process, the existing “accommodation” meets the criteria the Supreme Court asked both sides to address.

The government implores the justices not to require changes to the self-certification aspect of the “accommodation.”

The brief closes with an interesting plea to “definitely resolve” the challenge to the “accommodation” because it “affects the legal rights of …. tens of thousands of women who presently are not receiving the health coverage to which they are entitled by law.”

Conveniently, the government ignores the fact that it has grandfathered or otherwise exempted the insurance plans of 1 in 3 Americans from these requirements. (There are several large corporations, such as Exxon, Chevron, and Pepsi, which are exempt from the government’s regulation.)

The Little Sisters of the Poor and other challengers presented the Supreme Court with alternatives to the government hijacking their insurance plans, and the government insisted, once again, that these deeply religious employers are simply mistaken about their involvement in the “accommodation” process. Reply briefs are due next week, so stay tuned for the next development in this important case.