California schoolteachers appeared to be within striking distance of a landmark Supreme Court ruling that would uphold their right to free speech and end mandatory union dues.

That was before Justice Antonin Scalia died unexpectedly Feb. 13, leaving a 4-4 conservative-liberal split on the high court. Scalia, perhaps the court’s most conservative justice, was viewed widely as the swing vote in the case known as Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association.

But should the Supreme Court eventually rule in favor of the challenge of union power by Rebecca Friedrichs, a 28-year veteran of the Savannah School District in Anaheim, Calif., the results could be dramatic.

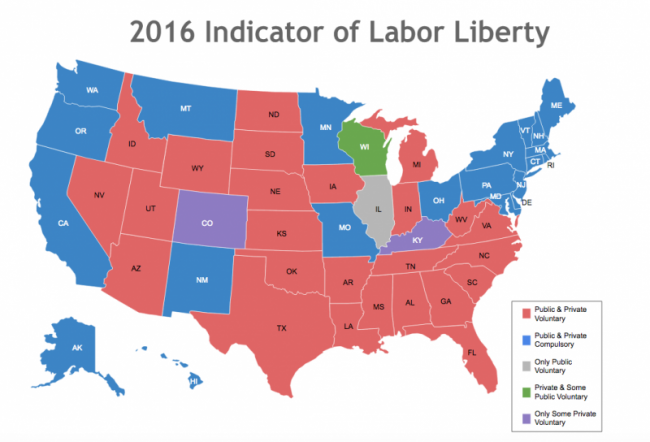

The Center for Worker Freedom, a project of Americans for Tax Reform, provides a detailed look in the form of the just-released “2016 Indicator of Labor Liberty,” maps that show how a ruling in favor of Friedrichs and nine fellow teachers would affect other parts of the country as the “right to work” movement grows.

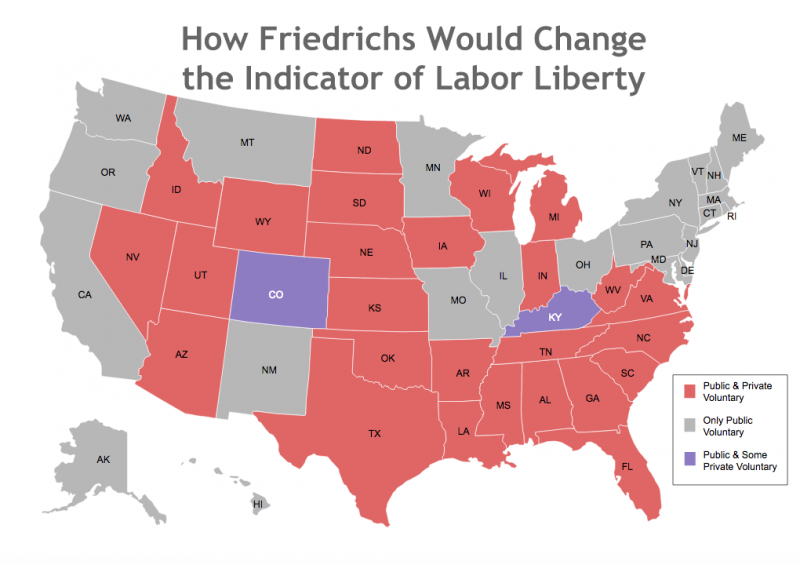

The center offers two versions of the map. One highlights the status quo of labor law across the country, the other demonstrates how government workers in 21 states would be freed from forced unionization if the high court rules mandatory dues unconstitutional.

Map: Center for Worker Freedom

Map: Center for Worker Freedom

“We went into each state’s constitution, and a lot of them had specific statutes and codes written into them with regards to ‘right-to-work’ either in the public or private sector,” Paige Halper, research fellow at the Center for Worker Freedom, told The Daily Signal. “We wanted to provide the most current and comprehensive classification of worker freedom.”

Right-to-work laws prohibit an employer and a union from signing a contract that would require workers to be union members. An “agency shop” requires that the workers who do not want to join the union pay the union a fee instead of union dues.

Lawyers for Friedrichs and the nine other teachers who took the education unions to court had been cautiously optimistic that Scalia would join with at least four other justices to rule in their favor based on comments he made Jan. 11 during oral arguments in the case.

Scalia had expressed skepticism toward the idea that political questions could be separated from the collective bargaining process; a point central to the plaintiffs’ case.

What happens next in the absence of a successor to Scalia—whom Senate Republicans have vowed not to vote on until the next president takes office—is a complicated question.

Court observers suspect the eight remaining justices are split evenly on the Friedrichs case, which would mean a 2014 ruling from the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals against the teachers, and for the unions, would remain in place.

But, as The Daily Signal previously reported, the Center for Individual Rights along with Michael Carvin, lead counsel for the teachers, have called on the high court to rehear the case once a new justice is name and confirmed.

If the court declines, lawyers for the teachers intend to file a motion for a rehearing.

Friedrichs, an elementary school teacher and the lead plaintiff in the case, wants that rehearing.

What the Case Is About

Friedrichs joined with nine other California teachers and the Christian Educators Association International to file suit against the California Teachers Association and several local unions. CTA is the state division of the National Education Association, also named as a defendant.

Under California’s “agency shop” law, teachers pay about $1,000 per year in union dues even if they don’t belong to the union. Non-union members can apply to be reimbursed for the portion of dues that goes to political advocacy, usually $300 to $400.

But this “opt out” process is cumbersome and difficult to navigate, Friedrichs and the other teachers in the case claim.

And as Scalia made clear during oral arguments, the collective bargaining process itself is laced with political overtones, making it more difficult to distinguish between what costs are “chargeable” to non-members what are “non-chargeable.”

In effect, this means that California teachers who are opposed to the political agenda of the teachers unions have to spend part of their work day financing political activism that cuts against their core beliefs, the plaintiffs argue.

This is also true of rank-and-file teachers across the country who oppose the far-left agenda embraced by many union leaders. Terry Pell, president of the Center for Individual Rights, has said the Friedrichs case must be re-argued before the Supreme Court since it involves a long-standing precedent that subverts First Amendment rights.

Rebecca Friedrichs, a California schoolteacher challenging union dominance, speaks with reporters Jan. 11 outside the Supreme Court after her case was heard. (Photo: Jeff Malet/SIPA/Newscom)

Mapping ‘Labor Liberty’

If Friedrichs and the other nine California teachers win a ruling against mandatory dues, after a rehearing or not, what would it mean for their state and others with similar agency shop laws?

The maps from the Center for Worker Freedom seek to provide a state-by-state answer. They measure labor freedom by the extent to which workers in the public (or government) and private sectors must support labor organizations.

Color schemes distinguish the states. Red states have the most worker freedom, because a worker’s decision whether to join a union or pay union fees is voluntary in both the public and private sectors. Blue states have the least freedom, because union requirements apply to both government and non-government workers.

In gray states, only the public sector allows a voluntary decision. Right now, Illinois is the one gray state.

If Friedrichs and the other teachers prevail at the Supreme Court, however, 21 other states now colored blue would switch to gray.

Some states present peculiar or special cases: Kentucky, Wisconsin, Colorado, and Illinois all have some worker freedoms juxtaposed with forced unionization.

The maps demonstrate why state labor laws must be clarified, Matt Patterson, executive director of the Center for Worker Freedom, said. Patterson told The Daily Signal:

There’s a lot of variation in how the laws and regulation are enacted from state to state. Colorado, for instance, has a bizarre, hybrid system where only some of the private sector is free. So, we are really finding a patchwork, which is why we thought a resource like this would be useful because of how contradictory and different these laws can be in certain states.

Map: Center for Worker Freedom

Map: Center for Worker Freedom

Mixed Conditions

While the Kentucky state legislature has failed to pass right-to-work legislation, 12 Kentucky counties passed laws banning mandatory union membership as a condition of employment.

In February, though, a district court judge ruled that only states may adopt right-to-work laws under the National Labor Relations Act, putting the county-level effort on hold.

Colorado is not a right-to-work state and so is not counted as “free” in the public sector. However, workers are partially free in the private sector under the Labor Peace Act. Union dues are not illegal for private sector workers, but the union must win two majority elections and the employer must agree to the contract.

Even if a Colorado union wins both elections, no all-union contracts will result if the employer refuses to enter the agreement. Put simply, private sector workers only pay dues in Colorado if the union wins both elections and the employer approves.

Illinois is not a right-to-work state, and private sector workers must pay dues. However, Gov. Bruce Rauner, a Republican, has issued an executive order that prohibits state agencies from exacting “fair share” fees from state employees who don’t choose to join a union.

After Michigan passed right-to-work legislation for non-government workers, the Michigan Supreme Court ruled that it also must apply to government workers.

In Wisconsin, anyone who works for a police or fire department must help fund a union even if the employee is not a member of the union.

‘A Lot of Momentum’

One development this year is incorporated into the latest version of the “labor liberty” maps.

On Feb. 12, West Virginia became the 26th right-to-work state, as well as the 25th “public and private voluntary” state, after the legislature overrode a veto by Gov. Earl Ray Tomblin, a Democrat, of right-to-work legislation.

Under right-to-work laws, private sector workers are not required to pay union fees or join a union as a condition of their employment.

“The biggest shift that would occur if the Supreme Court rules in favor of Friedrichs would be the shift from blue states to gray,” the Center for Worker Freedom’s Halper said. “Those blue states would become ‘free’ in the public sector. So you would see fewer colors on our map. The reason we have so many colors now is because there are so many exceptions and bizarre contingencies.”

Assuming the Supreme Court acts decisively in favor of Friedrichs at some point, the center’s Patterson said, a ruling that overturns forced unionization in the public sector will provide further impetus to right-to-work reforms in the private sector.

“If we do get right-to-work for the entire public sector, it’s going to create a lot of momentum and discussion about continued forced unionization in the private sector,” he said, adding:

I think laws are sometimes made purposely complicated and obtuse to prevent people from understanding what’s really permitted and not permitted. Right now, everyone is reticent to act in labor relations because there are so many complicated and conflicting rules. We hope these maps provide some much needed clarity.

A Matter of Interpretation

James Sherk, a labor economist with The Heritage Foundation whose expertise includes right-to-work trends, said the Center for Worker Freedom’s map highlighting the status quo of state labor laws is “mostly correct.” Sherk, however, said he would recommend clarifications with an eye toward legal action that could uproot existing right-to-work initiatives.

In Illinois, for example, Sherk points out that the governor’s executive order “is tied up in litigation and is not currently in effect.” Moreover, he says, the measure does not apply to local government employees such as school teachers.

But Patterson has a different interpretation.

“It’s true that Governor Rauner’s executive order in Illinois is under legal challenge, and may eventually be struck down,” he told The Daily Signal, adding:

As of now, however, it is on the books, and if public employees in Illinois are still paying dues, maybe they shouldn’t be until the order is struck down. Unless and until that happens, we consider Illinois public servants—and feel they should consider themselves—freed by executive order.

This report has been updated to include James Sherk’s observations.