OKLAHOMA CITY—Oklahoma state Sen. Kyle Loveless is not backing down.

The Republican has been called a liar and a socialist, in the pocket of organized crime, and al-Qaeda’s and ISIS’ best friend by officers of the law who protect and serve.

But in a year when Loveless, R-Oklahoma City, is up for re-election to the state legislature—a time when most lawmakers would choose not to stir the pot—the state senator has decided to challenge Oklahoma’s civil asset forfeiture laws, which some consider a “cash cow” for police and prosecutors because of their ability to seize cash and property without charging the owner with a crime.

“The way I look at it is, it comes back to should the government be able to take someone’s stuff and keep it without charging them or proving it, and I say no,” Loveless said. “If they’re going to keep calling me names, I’m a big boy. I can take it.”

This year, at least a dozen state legislatures across the United States are considering legislation to reform civil forfeiture laws.

But in no other state is the debate more contentious than in Oklahoma, where Loveless, who introduced a bill to challenge the current system, has been fielding attacks from prosecutors, sheriffs, and police officers for his efforts.

“Every way across the board in different agencies, city, county, statewide agencies, the system is fraught with abuse,” Loveless told The Daily Signal during an interview from his office in the state capitol. “Innocent people’s stuff is being taken. The system is so perverted that it is like climbing Mount Everest to get your stuff back.”

Apache, Okla., Chief of Police Stephen Mills had his Ford F-250 seized by law enforcement in 2010. He’s since come out as a vocal opponent of civil forfeiture. (Photo: Patchbay Media/The Daily Signal)

‘It Was Stealing’

Civil forfeiture is a tool that gives law enforcement the power to take people’s cash, cars, and property if they suspect it’s connected to criminal activity. The procedure was expanded in the 1980s and hailed as a tool law enforcement needed to fight the war on drugs.

In recent years, civil forfeiture has been dubbed “policing for profit” by opponents, a term used to describe the money-making scheme civil forfeiture creates for police and prosecutors, since law enforcement doesn’t have to charge people with a crime to take their cash, cars, or houses.

In Oklahoma, anecdotes involving innocent people who had property and cash wrongfully seized by police under civil forfeiture have emerged, and such stories have fueled Loveless’ efforts to reform the state’s laws.

In 2010, for example, Grady County ranch owner and operator Stephen Mills, who was in the military at the time, had his truck taken by the Grady County Sheriff’s Department after he lent it to a ranch employee to use.

The worker was arrested for stealing equipment from an oil field, and law enforcement seized Mills’ truck under civil forfeiture.

Mills, who currently serves as the police chief in Apache, Okla., called the Sheriff’s Department twice a week for four months asking them to return his vehicle. They eventually stopped returning his calls.

“It was stealing,” Mills told The Daily Signal during an interview at his Grady County ranch. “It doesn’t matter if they had the color of the law behind them. They were stealing.”

Six months after the Sheriff’s Department took Mills’ truck, he made a phone call to the Chickasha Express Star, a newspaper, which called the district attorney’s office for a comment.

Not long after, a lawyer assisting Mills told him he could go pick up his truck.

The military veteran has been a vocal opponent of civil forfeiture, and his case isn’t unique.

In March 2012, Creek County, Okla., sheriff’s deputies raided a home belonging to Linda Goss and her husband. The couple was arrested for allegedly having illegal drugs in their home, and police seized firearms, a fishing boat, and a truck under civil asset forfeiture.

Goss and her husband spent three days in jail, only to learn that police had raided the wrong home.

Charges against the couple were dropped, and, according to a lawsuit they filed, tests showed that the alleged illegal drugs weren’t drugs at all.

Goss and her husband couldn’t afford the impound fees for the truck, which they lost. Their boat was returned, but they said it was damaged.

“When law enforcement says they’re going after [the drug trade], I’m sure they are, because we see the busts all the time, and I think we should have the tools to do that,” Loveless said. “However, the problem is, we shouldn’t balance that on the backs of innocent people’s stuff.”

State Sen. Kyle Loveless, R-Oklahoma City, has been criticized by law enforcement for his bill reforming the state’s civil asset forfeiture laws. (Photo: Patchbay Media/The Daily Signal)

‘Back to the Constitutionality’

After learning about how innocent Oklahomans can get caught in the civil forfeiture machine, Loveless introduced legislation in May implementing a number of changes to the state’s civil forfeiture laws.

Loveless said he planned to address the original bill this year and meet with law enforcement in the interim to address any concerns they may have. But the backlash from police and prosecutors was so swift that he decided to draft a second proposal that he hoped tackled concerns from civil forfeiture opponents and supporters.

The second version of Loveless’ bill, released last month:

- Requires a criminal conviction before property can be forfeited. The legislation also allows for five exemptions in which property can be tied to a crime—and subsequently forfeited—without a conviction.

- Directs forfeiture proceeds to a fund managed by a 15-person board made of Oklahoma citizens and members of the law enforcement community. The board has the authority to award grants to drug treatment centers, drug courts, and law enforcement for drug interdiction efforts.

- Raises the burden for the government to justify property seizures.

- Requires agencies using civil forfeiture to provide an annual report to state leaders. The report would be made publicly available online.

Opponents of civil forfeiture say the system creates a perverse profit incentive for law enforcement to seize property from innocent people, since police and prosecutors can use forfeiture proceeds to pad their budgets and purchase items without oversight from appropriators.

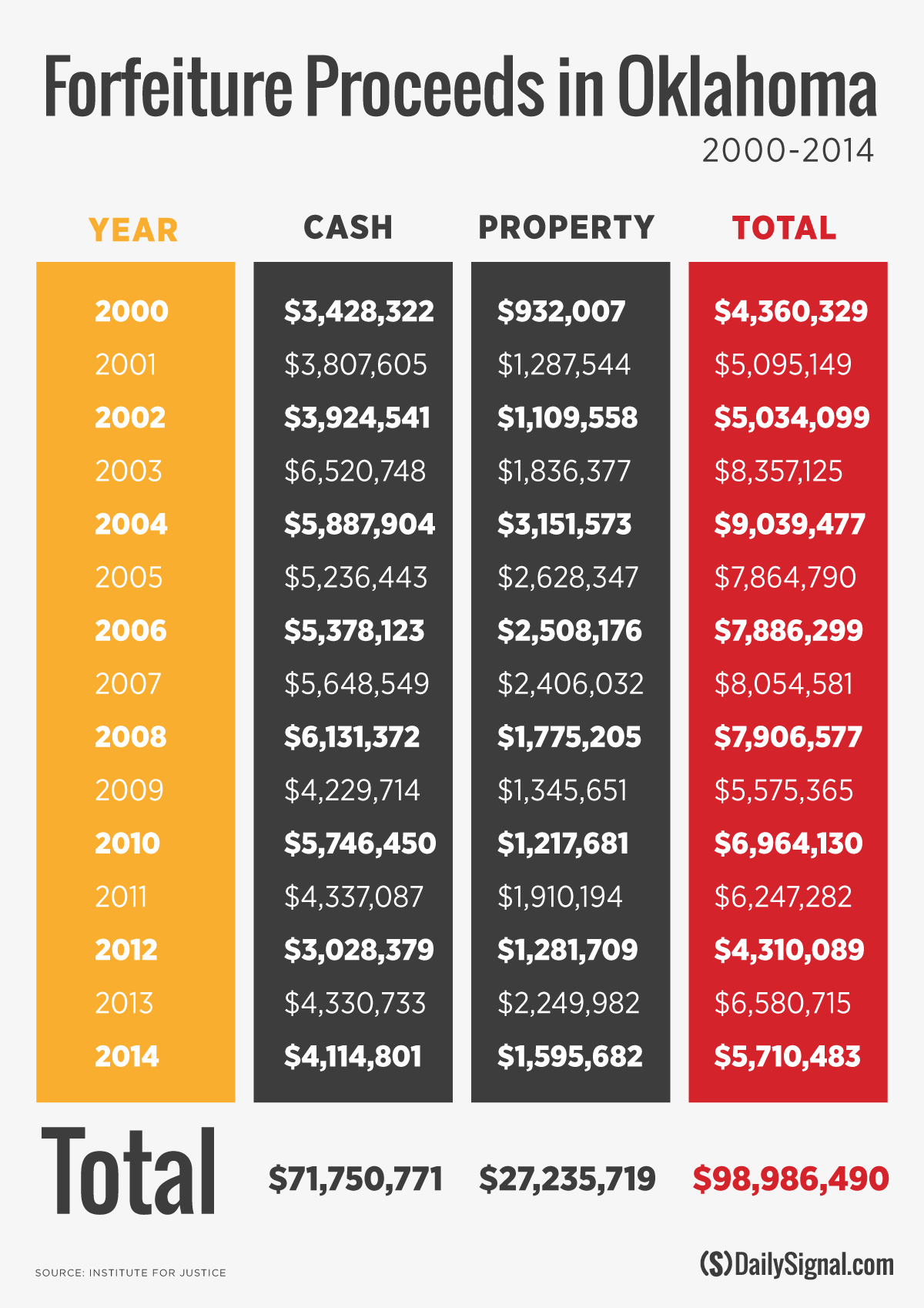

A report from the Institute for Justice found that from 2000 to 2014, state law enforcement agencies reported nearly $99 million in forfeiture proceeds, of which 72 percent came from cash seizures. Current state law allows agencies to keep up to 100 percent of forfeiture proceeds.

Loveless credits his bill with eliminating that profit incentive while also ensuring that law enforcement has the tools necessary to combat drug crimes.

“We have sheriffs out there and agencies out there [who] if in their budget they want an armored humvee and their budget appropriators don’t give it to them, they’ll just use the money to go get it,” Loveless said.

Contrary to Loveless’ concerns, Mark Woodward, spokesman for the Oklahoma Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, and other law enforcement groups say there are safeguards in place to ensure that civil forfeiture protects Americans’ constitutional rights.

“We believe Oklahoma has, when it comes to our opposition to changing the current system, one of the best systems in the country,” Woodward told The Daily Signal. “In Oklahoma, it goes back 200 years to the Constitution. We still have to have probable cause. That’s a safety net that’s in place for the public who believe that this is sort of an infringement on the Constitution or on their rights.”

Despite Loveless’ efforts to pass a package reforming Oklahoma’s civil forfeiture laws, he hit a roadblock in the state legislature.

Last week, the Senate Judiciary Committee refused to take up his legislation, and reports suggest that the package was “sent there to die.”

Loveless said he still has options and plans to use every tool at his disposal to at least get some aspects of his proposal to the Senate floor.

The Oklahoma City Republican can move to put the full bill directly on the Senate’s agenda, though he would need to secure a supermajority to be successful.

Loveless can also amend another bill addressing civil forfeiture to include some aspects of his proposal once it gets to the Senate floor. That bill, which the Judiciary Committee passed unanimously, addresses the repayment of lawyer fees and expenses for those who successfully challenge a forfeiture.

“Oklahomans of all walks of life and political ideologies support civil asset forfeiture reform,” Loveless said in a statement after the Judiciary Committee passed on the bill. “However, [the committee chairman] did not think their voices should count in the political process.”

Despite the setback, both Loveless and Mills agree that law enforcement’s use of civil forfeiture in Oklahoma represents a nationwide trend, one that must be addressed.

“This isn’t just a problem in Oklahoma,” Mills said. “It’s a national problem. We need to change the whole mindset on a national level to take it back to the constitutionality of what’s being done.”

From 2000 to 2014, law enforcement agencies in Oklahoma reported nearly $99 million in proceeds from forfeitures of cash and property. (Photo: Patchbay Media/The Daily Signal)

Keeping the Cash

Woodward said Stephen Mills’ and Linda Goss’ experiences are spread to deliberately overshadow the thousands of legitimate civil forfeitures conducted every day by law enforcement nationwide and officers’ need to use the tool.

“Civil asset forfeiture allows us to take illicit drug proceeds that would normally go back to line the pockets of the cartels and fuel their business and take it out of their hands to harm their efforts,” he said. “Every time we can make a dent in what’s going back to fuel a particular cell of that cartel, it can harm that cartel’s operations.”

Anecdotes from innocent Americans who have property seized, Woodward argued, are spread to gin up support for reforms.

“It’s isolated cases. That’s like somebody who said that the surgeon botched the surgery on them. That’s going to happen, and that’s sad, and there are as many as five to 10 horrible surgeries that take place in this country, but there are millions of successful surgeries, and that’s where the focus needs to be,” he said.

“If there’s a bad surgery, you go deal with the surgeon, the surgical staff, and the hospital. You don’t bulldoze this nation’s medical laws and start from scratch because of a few cases. It’s the same with this. What’s getting ignored is the thousands just here in Oklahoma alone, the successful seizures, against drug organizations.”

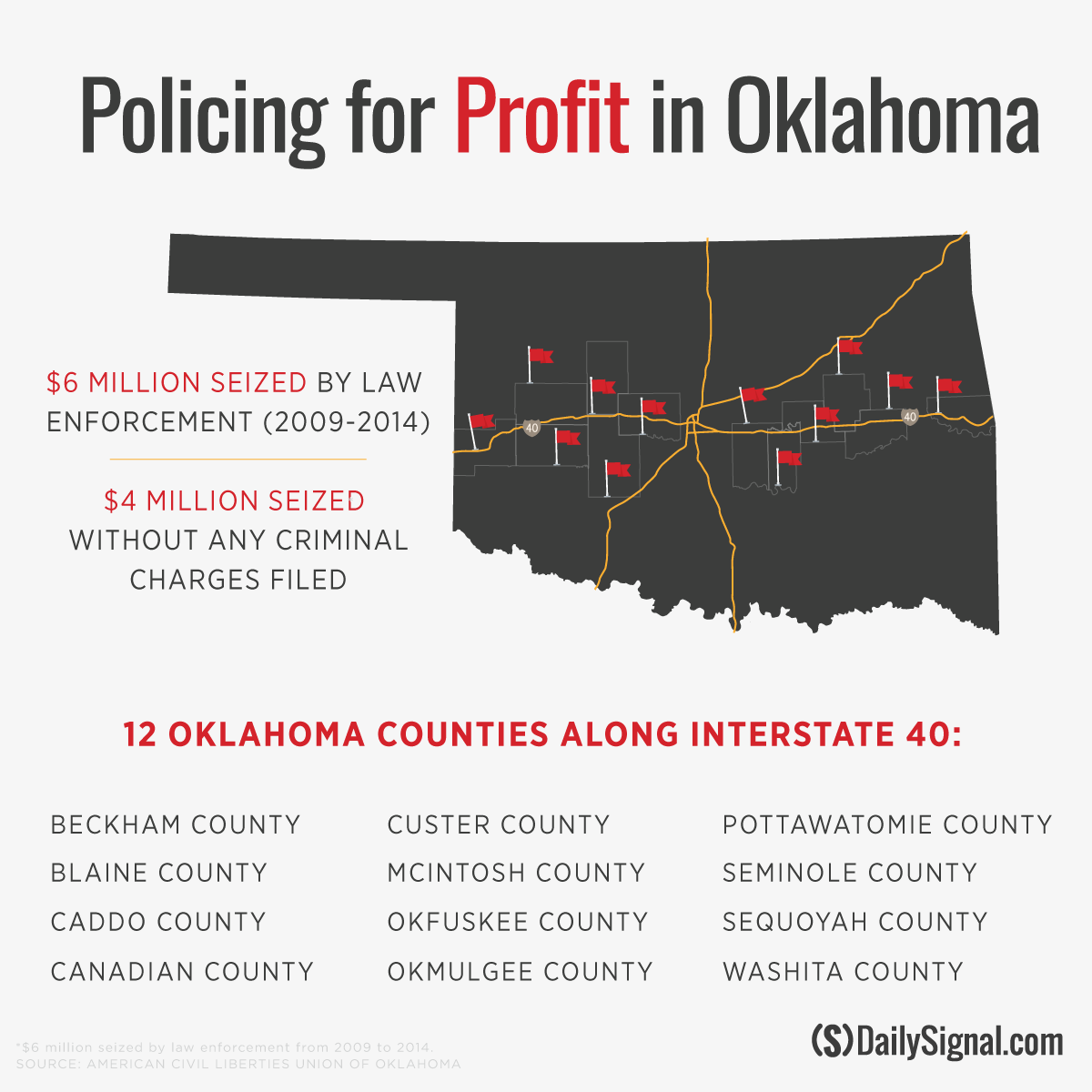

Many cash forfeitures in Oklahoma occur along Interstate 40, a major highway that bisects the state.

According to a report from the American Civil Liberties Union of Oklahoma, law enforcement agencies in 12 counties located along the I-40 corridor seized $6 million in cash from property owners from 2009 to 2014. Of the money taken during that five-year span, just $2 million belonged to those charged with a crime.

Loveless said that oftentimes, police will pull over a car as it is heading out of a major city along I-40 and seize cash they assume came from the sale of drugs.

But Loveless questions why law enforcement doesn’t intercept the cars before drugs are sold and on Oklahoma streets.

“Because they can keep the cash,” he said, “and use the cash.”