The crisis of unaccompanied Central American children illegally crossing the United States’ southern border does not end when they enter this country.

As the children arrive and settle in the U.S. and wait to hear their fate in immigration court, some are placed into homes where they are sexually assaulted or forced to work.

Meanwhile, the agency tasked with placing the children into U.S. communities has no system for tracking them once they are united with sponsors—people who are supposed to keep them safe and ensure that they show up for immigration court.

These are the findings of two recent investigations—one by a Senate subcommittee and another by the Government Accountability Office—into what has become of the tens of thousands of children who have fled violence in Central America over the last few years.

“It’s a tragedy,” said Sen. Ron Johnson, R-Wis., the chairman of the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, who, along with other Senate leaders, asked the GAO to review the Obama administration’s response to the unaccompanied minor crisis.

“People have said the crisis is over, but it only doesn’t seem like a crisis because we have gotten more efficient at apprehending, processing, and dispersing the children—and then ignoring them,” Johnson told The Daily Signal.

The William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 provides protection for children entering the U.S. alone who are not from Mexico or Canada by prohibiting them from being quickly sent back to their home countries.

Instead, the Office of Refugee Resettlement, an agency of the Department of Health and Human Services, provides shelter for unaccompanied children from Central America and finds sponsors to care for them while they await hearings in immigration courts.

According to the GAO report released Monday, the Office of Refugee Resettlement had been used to caring for a steady number of children for a number of years. From fiscal years 2003 through 2011, the agency cared for less than 10,000 unaccompanied children per year.

Beginning in fiscal year 2012, the number of unaccompanied children apprehended at the southwest border by the Department of Homeland Security and transferred to the Office of Refugee Resettlement rose dramatically, peaking in fiscal year 2014 at nearly 57,500.

On Tuesday, the Senate Judiciary Committee will hear testimony from Obama administration officials as lawmakers seek to find more answers about the unaccompanied children crisis.

Johnson, who is not on the committee, believes that the response to the crisis should start at the beginning and be focused on deterring illegal immigration to the U.S.

He argues that the U.S. government’s responsibility to shelter and provide a hearing to unaccompanied children from Central America has incentivized immigrants to take the dangerous journey here.

He also says President Barack Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, known as DACA, encourages children to come to the U.S.

While recent border crossers are not eligible for the program, Johnson thinks it sends the message that the U.S. government will provide refuge to children who come here illegally, no matter if they qualify for protection under U.S. law.

“Rather than adding more beds and facilities and getting more efficient at apprehending and dispersing the children, we’ve got to look at these policies and see what’s incentivizing the children to come here,” Johnson said.

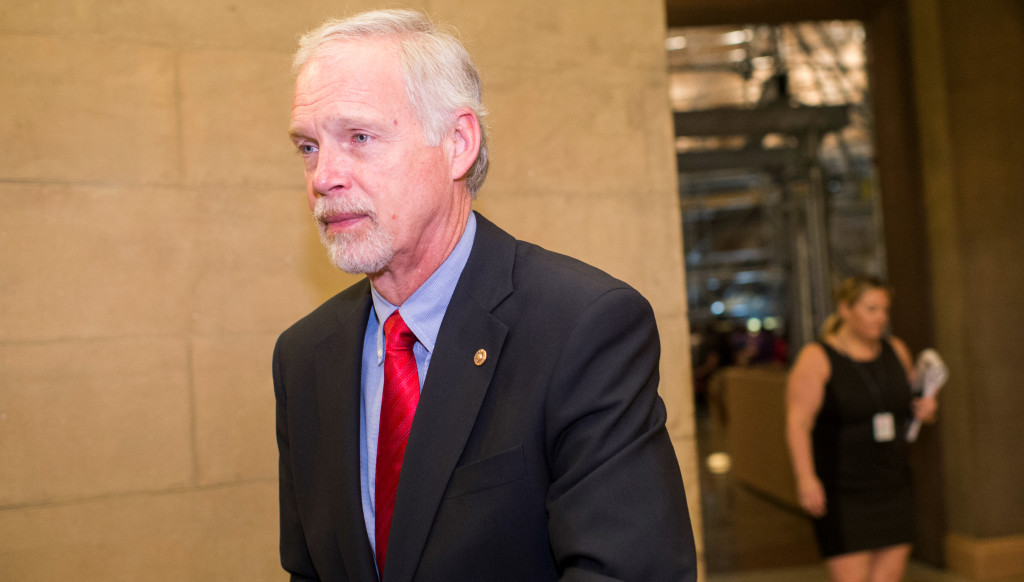

Sen. Ron Johnson, R-Wis., has been critical of how the federal government has responded to the unaccompanied minor crisis of 2014. (Photo: Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call/Newscom)

Melysa Sperber, the director of the Alliance to End Slavery and Trafficking, agrees that the U.S. government needs to slow down the flight from Central America.

But she says the fix is closer to home.

“We really believe it is a humanitarian crisis, and rather than helping Mexico install tighter border controls to interdict women and children fleeing violence, the U.S. government should be focused on the root causes of the crisis and invest in stronger child protection systems, and strengthen the rule of law, to reduce impunity in Central America,” Sperber told The Daily Signal.

Officials from the refugee resettlement agency have acknowledged they were overwhelmed in 2014 but have since upped their capacity to shelter the children. The federal government has increased the number of nonprofit groups that it pays to operate shelters for the children and locate sponsors from 27 such organizations that ran 59 facilities to 57 that are managing 140 facilities.

“This may be a system that worked reasonably well with a steady population, but in the last two years, as things peaked very quickly and the systems were under strain with the unanticipated sharp changes, that’s when things started to crack,” said Doris Meissner, who leads the U.S. Immigration Policy Program at the Migration Policy Institute.

In the haste to keep up with the numbers, the Office of Refugee Resettlement has undertaken policy changes, such as forgoing fingerprinting as a component of background checks for sponsors who are parents or legal guardians with no criminal or child abuse history.

On Jan. 28, the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations issued a report showing that the refugee resettlement agency sometimes fails to verify the relationship between an unrelated adult sponsor and unaccompanied child. Indeed, the refugee resettlement agency stopped requiring original copies of birth certificates to prove most sponsors’ identities.

Since the rule changes, children were released to sponsors who subjected them to sexual abuse, labor trafficking, or neglect.

The more recent GAO report traces the problems with caring for the refugees earlier in the process. Office of Refugee Resettlement officials say that, because of a lack of resources, the agency has gone years without visiting and monitoring some of the nonprofit-run facilities that shelter the children before they are released to sponsors.

In the rare instances where refugee resettlement officials do personally visit the facilities, they can find problems. According to a report reviewed by the GAO, Refugee Resettlement officials found that one facility failed to medicate children properly, which, in one instance, led to accidental overdoses of medicine.

In addition, while the shelters are required to provide medical and mental health services to children who need them, and education to all, the GAO found that children’s case files were often incomplete, making it difficult for investigators to determine whether they had received the care they needed.

Meanwhile, later in the process, the Office of Refugee Resettlement does not often visit the homes of sponsors who end up claiming responsibility for the kids.

By law, the refugee resettlement agency is only obligated to do home visits of sponsors in certain circumstances, such as when the person is a non-relative, and when the child is younger than 12 or a victim of trafficking or other abuse.

“Obviously these abuses are terrible, and nobody would want this to be happening, but I think in looking at this, one of the issues that’s important to untangle is what ORR’s actual obligations are supposed to be,” said Meissner, who argued that state and local governments need to take on more responsibility for supervising the children.

The Office of Refugee Resettlement recently took steps to expand the services it provides to children after they are released to sponsors, including creating a National Call Center for children who experience “disruption” in the custody of their sponsors.