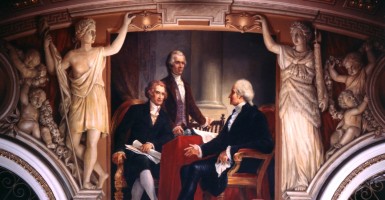

This February is the 225th anniversary of Alexander Hamilton’s and Thomas Jefferson’s famous 1791 debate—carried on in President George Washington’s cabinet—over the constitutionality of Hamilton’s proposed Bank of the United States.

It might seem strange to call such an anniversary to mind. After all, we usually celebrate our great moments of national agreement (like the Declaration of Independence), not of controversy. It might even be a little painful, since the bank bill argument was only the opening shot in a bitter political and constitutional battle between Washington’s two chief ministers.

Nevertheless, it is proper to celebrate and reflect on this first major constitutional dispute in our history. Hamilton and Jefferson disagreed about the correct interpretation of the Necessary and Proper Clause and therefore about the legitimate scope of the powers of the federal government.

>>> Order Carson Holloway’s Book “Hamilton versus Jefferson in the Washington Administration: Completing the Founding or Betraying the Founding?”

They agreed, however, on something more fundamental. What united them was the importance of constitutional fidelity, or the need to make sure that government policy is guided by the true meaning of the Constitution.

At first sight, Jefferson emerges as the Constitution’s champion in this dispute. Hamilton’s initial report calling for a national bank did not even bother to bring forward any constitutional basis for such a measure.

It was Jefferson, following James Madison’s lead, who contended that the Necessary and Proper Clause could not be pushed so far as to justify the creation of such an institution. Nevertheless, in the clash of argument over the question Hamilton, too, established his constitutional seriousness.

He replied to Jefferson at impressive length, trying to show that Jefferson had misunderstood the Necessary and Proper Clause, that it could reasonably be read to authorize laws that were, if not indispensable to, at least reasonably related to the exercise of the government’s enumerated powers.

Hamilton prevailed, and George Washington signed the bill into law. This reminds us of Washington’s often overlooked role in our first great constitutional debate: He caused it by calling for Hamilton and Jefferson’s written opinions of the question of the bank’s constitutionality. In doing so, Washington set a high example of constitutional statesmanship and earned, once again, his unique position of honor among our nation’s presidents.

Washington, who usually followed Hamilton’s advice on matters of domestic policy, surely favored the bank bill. And since it had been passed easily in both houses of Congress, after Madison had raised his constitutional objections in the House, Washington had plenty of political cover, had he wanted to exploit it, to simply sign the bill and move on. That he instead called for further argument within his own cabinet shows that he was utterly serious about keeping his administration’s policy square with the Constitution.

We live in a time of widespread constitutional unseriousness. It is a time in which a speaker of the House, asked about the constitutional basis of a bill pending before the Congress, can answer, “Are you serious?” In such times, we sorely need the example of such statesmen as Jefferson, Hamilton, and Washington.