Professors in higher education have become notably more liberal during the past 25 years, according to a recent study, and academics predict that the trend isn’t likely to slow any time soon.

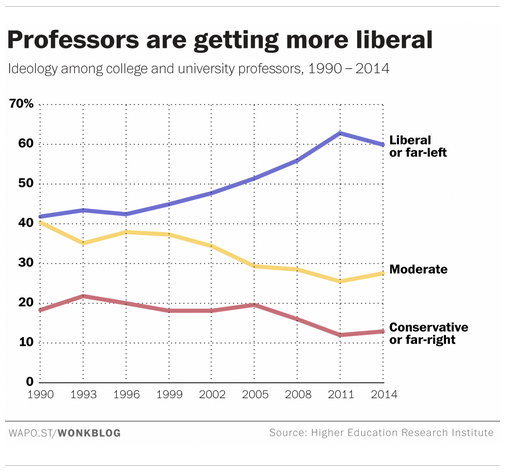

During the past quarter-century, academia has seen a nearly 20-percent jump in the number of professors who identify as liberal. That increase has created a lopsided ideological spread in higher education, with liberal professors now outpacing their conservative counterparts by a ratio of roughly 5 to 1.

In 2014, 60 percent of professors identified as “liberal” or “far left,” according to the Higher Education Research Institute at UCLA, as reported by The Washington Post’s “Wonkblog.”

Compare that with 1990 survey data, when only 42 percent said the same.

While academia has shifted dramatically to the left, professors on the right have dropped off.

The number of professors who identified as “conservative” and “far right” during the same time span fell by nearly 6 percent, while the number of “moderate” academics dropped by 13 percentage points.

Matthew Woessner, an associate professor of political science and public policy at Penn State Harrisburg, studies political trends in higher education and advocates increased diversity of viewpoints with a group of academics who call themselves Heterodox Academy.

Woessner, who says he is a conservative Republican, said the study raises important questions on whether the liberal tilt that has persisted in higher education is becoming more pronounced, and if so, what impact that has on the national political discourse.

Daniel Klein, a professor of economics at George Mason University, said the reported 5-to-1 ratio is “not very meaningful” because the terms “liberal” and “conservative” have become “exceedingly troubled.”

Instead, Klein predicted that the imbalance between faculty who vote Democratic compared with those who vote Republican is closer to 9 to 1 or even 10 to 1.

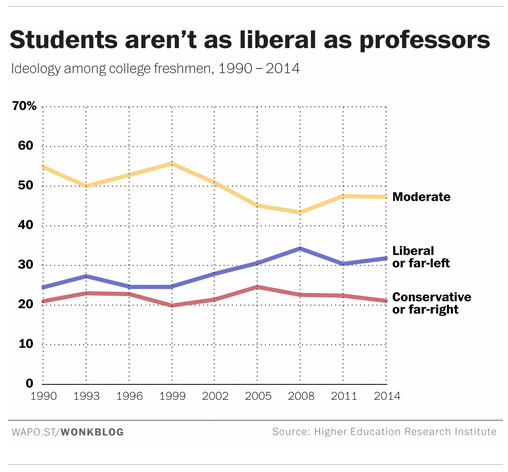

Either way, as professors have become more liberal, they’ve shifted far to the left of the general public and their students, Woessner told The Daily Signal.

A Gallup poll released earlier this month found that 38 percent of Americans identify as conservative, versus 24 percent who identify as liberal.

And while the study by the Higher Education Research Institute reported that liberal students outpace conservative students by nearly 10 percent, roughly half identify as moderate. This has created a wide ideological gap between professors and students.

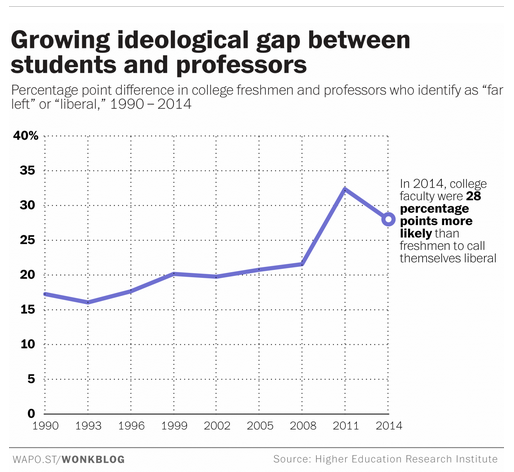

In 2014, college professors were roughly 30 percentage points more likely to identify as liberal than were college freshmen. Compare that to the 1990 findings, when professors were 16 percentage points more likely to label themselves as liberal than were their freshmen students. Woessner said:

This raises critical questions of whether students are getting a balanced education—not because there’s some conspiracy to block out conservative ideas, but merely because the people who are teaching are either not familiar with or don’t embrace conservative ideas.

Even when faculty attempt to present an issue in a balanced and impartial manner, he said, personal biases naturally bleed into material.

According to 2009 data from the Higher Education Research Institute, the number of students who said their political views were “liberal” or “far left” jumped 9.2 percentage points from freshman to senior year.

Carson Holloway, an associate professor of political science at the University of Nebraska Omaha, said the imbalance is most notable in the humanities and social science fields, where the battle of ideas is most important.

Holloway, who also chairs the Council of Academic Advisers at The Heritage Foundation, said the average political scientist in the U.S. is a “mainstream” liberal.

The problem with this, he said, is that a lot of “impressive” thought stemming from Europe fostered conservative ideology, but because not many in the academy represent that tradition, students get a skewed view.

“They might tend to think that conservatism is not an intellectual tradition because they don’t see any professors who hold to it, so there’s a distortion that emerges there,” Holloway told The Daily Signal.

Woessner said the students who are harmed the most by the bias in academia are the liberal ones:

Conservatives benefit from having liberal ideas to expand their horizons and challenge their thinking, but ideologically liberal students get their ideas reinforced. This means they’re not growing intellectually because they don’t have the exposure to other ideas to make them think.

Woessner said an equal number of liberal and conservative professors isn’t necessary for higher education to work well, but at least a small minority of faculty on campus should hold different views.

Conservatives who want to become involved in higher education face challenges, he said, and universities should encourage more right-leaning academics to become professors to help shrink the ideological gap.

“The goal should not be an even split, because that’s probably impossible, but to create a space for enough conservative ideas that students are exposed at least nominally to these other perspectives,” Woessner said.

And although a prescriptive fix to obtain greater balance won’t happen on its own, Klein said, “donors, students and parents should vote with their dollars, and voters should vote with their votes against pouring taxpayer money into a leftist apparatus.”