Conservatives pushing for easing mandatory minimum prison sentences are using an unlikely selling point to their instinctively tough-on-crime colleagues: the story of Oregon ranchers whose terms of incarceration sparked the armed occupation of a federal wildlife refuge.

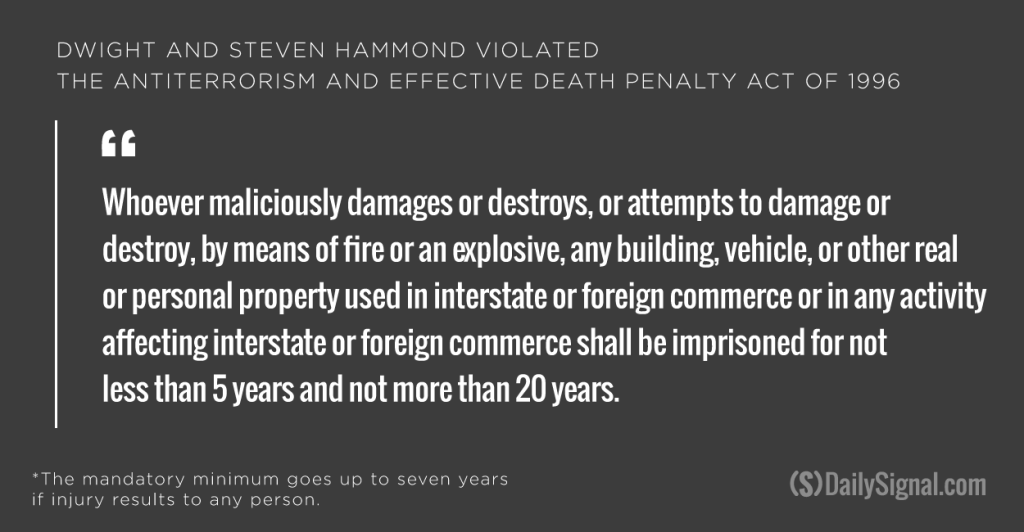

Federal law required ranchers Dwight and Steven Hammond to be given five years in prison for starting fires that spread to federal land, even though a district court judge originally rejected the mandatory minimum sentence because he said the terms are “grossly disproportionate to the severity of the offenses.”

But the district court’s sentencing was reversed by the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which upheld the terms required by the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act and imposed a five-year prison sentence on the Hammonds.

The father and son reported to federal prison this week, after having already served shorter sentences under the district court ruling.

Also this week, a group called the Citizens for Constitutional Freedom has been occupying an empty federal building located on the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge to protest the Hammonds’ sentence, and to broadcast their larger concerns over federal control of land.

The Hammonds have distanced themselves from the protest.

>>>Why Federal Law Enforcement Is Taking a ‘Wait and See’ Approach to the Oregon Protesters

Though proposals in Congress are focused on reducing mandatory prison sentences for drug offenders, who make up about half of the overburdened federal prison population, the Hammonds’ case could perhaps be received more sympathetically by those who view drugs as a means to violence.

“One of the unintended consequences of what is happening in Oregon is that people realize that when you are talking about these sentences, you are not just talking about people on drugs, you are talking about just the fact the federal government has so much control and judges have so much control over what happens,” said Rep. Raul Labrador, R-Idaho, a leading conservative criminal justice reform advocate, in an interview with The Daily Signal.

“There are moments where you see even the judge wants to go outside the sentencing guidelines and they can’t.”

Mandatory minimum sentencing laws, most of which were enacted during the tough-on-crime period of the 1980s and 1990s, require binding prison terms of a particular length and prevent judges from using their discretion to apply punishment.

Both the House and Senate Judiciary Committees, with bipartisan support, have introduced legislation to reform federal sentencing laws, and President Barack Obama has declared the issue one of the few he thinks he can work with Congress this year.

>>>Senators Reach Long-Elusive Deal to Reduce ‘Unjust’ Prison Sentences

But some advocates had been worried momentum for the cause had been going the other way, after the White House openly disputed a House proposal to include a “mens rea” measure requiring prosecutors to prove that suspects knowingly broke certain federal criminal laws.

Meanwhile, some critics of criminal justice reform have been trying to stoke worries by pointing to rising murder rates in certain cities last year as a reason to not reduce drug sentences.

“There seems to be a mobilization in talk radio against repealing mandatory minimums and I think those folks discussing that need to take a look at what’s happening in Oregon and reevaluate their stance,” said Rep. Thomas Massie, a conservative criminal justice reform supporter from Kentucky, in an interview with The Daily Signal.

“This is not a Republican or Democrat thing, just like having a peaceful protest is not a Republican or Democrat thing, so I am still hopeful we can get something done on it, maybe in the context of this current situation out west.”

To be clear, none of the proposals in Congress reducing mandatory minimums would have helped the Hammonds.

Still, criminal justice reform advocates say the Hammonds’ case is representative of what they see as the broader problems of mandatory minimum prison sentences.

“We like to think there’s a neat distinction between violent and nonviolent offenses,” said Molly Gill, government affairs counsel of Families Against Mandatory Minimums. “We want to draw a bright line, and say only drug users, not sellers, are nonviolent.”

“This case shows it’s not as black and white as we want it to be, and that it’s important to have laws flexible enough to give judges the ability to point to truly nonviolent offenders and say this is a violent offense and needs lengthy punishment, and laws flexible enough for judges to recognize when someone is not violent.”

The federal law by which the Hammonds were punished, the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, was passed by Congress in 1996 with the support of President Bill Clinton.

Gill said the law was primarily intended to punish terrorism offenses, as the law’s name suggests, but it also defines how the government deals with arson on federal property.

The law’s scope of punishment has probably gone farther than its writers intended, and the Hammonds’ case shows the disconnect that can occur when the federal government creates criminal law, Gill said.

“It’s a great highlighter of the importance of local control over crime,” Gill said. “The federal government is not supposed to be writing vast quantities of criminal law. Criminal law is supposed to reflect community values of right or wrong. The [district] judge made a decision he felt was appropriate for this community, for these offenders, for what they did, but because of mandatory minimum sentencing laws, the punishment does not fit what the community wants.”