In a reprise of the humanitarian crisis of summer 2014, rising numbers of Central American children and families are crossing the Rio Grande Valley into Texas, causing a reckoning over whether the U.S. is facing a “new normal” of illegal migration from countries facing violence and poverty.

Though the U.S. is better prepared to handle the influx compared to last time, immigration experts caution that the problem is likely to sustain beyond a surge, with many of the cases from last year yet to be adjudicated in overburdened immigration courts and more coming.

“It’s honestly the next chapter in an ongoing crisis,” said Wendy Young, president of Kids in Need of Defense, a Washington, D.C., nonprofit that represents unaccompanied children in deportation proceedings.

“We are wondering what comes next. There is a reality to this situation that we need to wrap our head around.”

“It’s honestly the next chapter in an ongoing crisis,” says Wendy Young, president of @supportKIND.

Here’s what’s coming now:

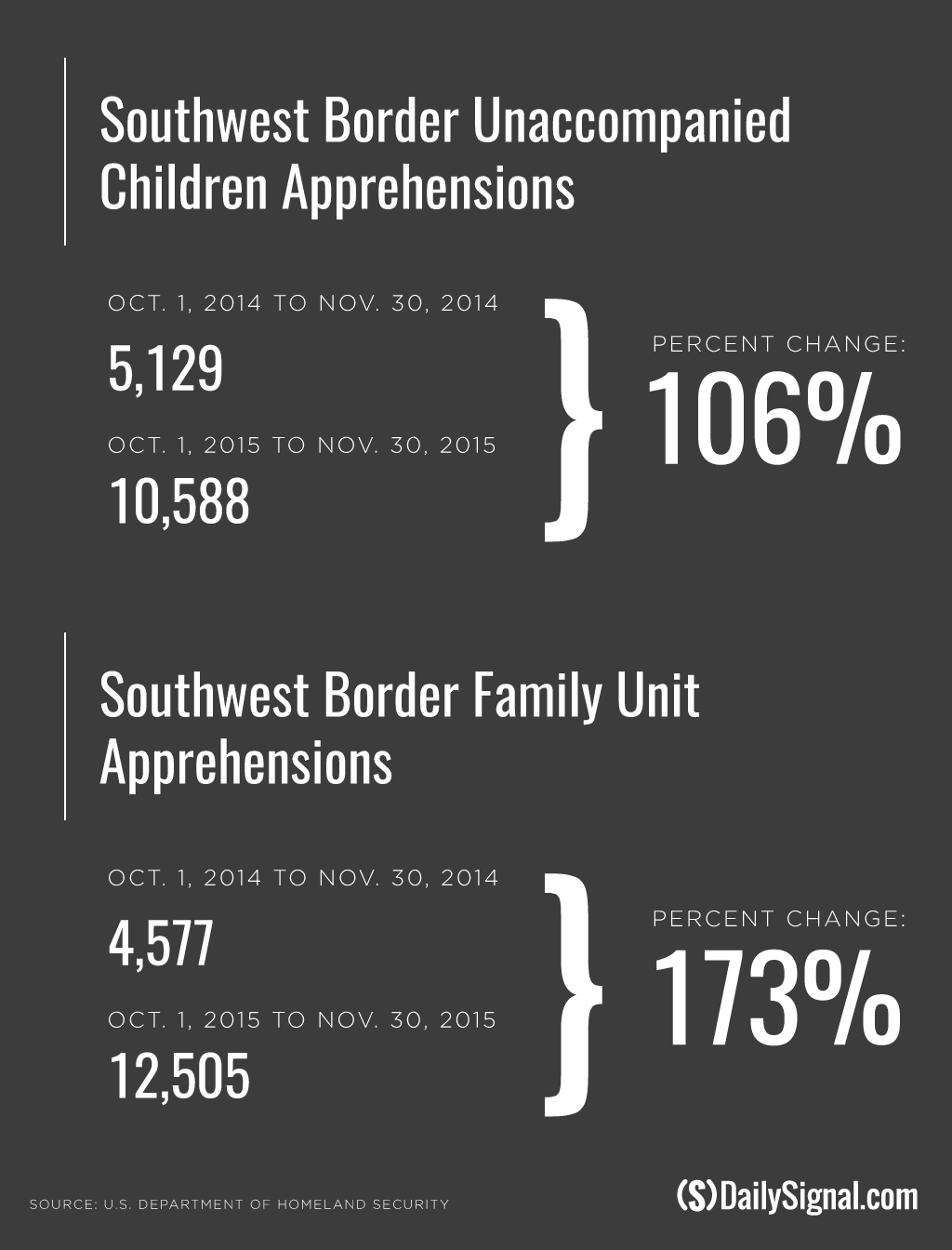

In October and November, more than 10,500 children—mostly from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras—crossed the U.S.-Mexico border by themselves, a 106-percent increase compared to the same period last year.

In addition, more than 12,500 family units (usually a mother with her children) have come that way since Oct. 1, representing a 173-percent increase over the same time last year.

These numbers are still smaller than the summer of 2014, when more than 10,600 unaccompanied minors crossed the border just in June.

But the spikes are causing alarm because crossings of the southwest border had declined after Mexico began better enforcing its borders—with help from the U.S.—and the Obama administration pursued a public awareness campaign in Central America discouraging people from migrating.

The timing is also surprising because peaks in illegal immigration usually occur during the summer, when the weather is more bearable.

The positive trends have proven temporary impediments to opportunistic smugglers who have found new routes into the U.S. and desperate people willing to risk more for the chance at a better life.

“This may be the new normal,” said Marc Rosenblum, the deputy director of the U.S. immigration policy program at the Migration Policy Institute. “Everything that was going on in 2014 that caused people to flee is as bad or worse now. Violence in El Salvador is worse, the whole region is amidst a two-year drought, more families are experiencing food insecurity, there’s political turbulence in Guatemala. Those are strong pressures that will cause people to try to get here.”

Under pressure to respond to the surge more efficiently than last time, the Obama administration is adding at least 1,400 beds for unaccompanied children, opening three shelters this month, including two in Texas, according to The New York Times.

After children from Central America are apprehended by the Border Patrol, the Department of Health and Human Services is required to shelter them until it can find a sponsor in the U.S.—usually a parent or other family—for them to stay with.

In addition, an omnibus government spending bill signed earlier this month contains money for the hiring of 55 immigration judges to handle a backlog of 463,627 pending cases (as of November) in immigration courts nationwide, according to Human Rights Watch.

All Central American children must have their cases heard by an immigration judge.

Family units get a hearing before a judge too if they pass a “credible fear” interview with an immigration official pledging to their hope for asylum.

According to Rosenblum, half of the cases that began in immigration courts in 2014 are still pending, and two-thirds of cases brought this year are unresolved.

“We still have such poor capacity to quickly adjudicate claims,” Rosenblum said. “Waits at immigration court remain very long. Very few are deported back, and few cases are resolved quickly.”

“Very few are deported back, and few cases are resolved quickly,” says Marc Rosenblum of @MigrationPolicy.

Border officials argue that a factor fueling the current surge is a reduction in detention of women and children required by federal court rulings from this year.

The decisions found that two detention centers in Texas that the Obama administration opened last summer failed to meet the standards of a 1997 settlement agreement for facilities housing children.

While the government is appealing, an official with the Department of Homeland Security told The Daily Signal that the administration is taking steps to comply with the order, and that “family residential centers are more and more functioning as processing centers for interviews and screenings.”

Though the official could not comment on the nature of the compliance due to the ongoing litigation, Rosenblum and other immigration experts say the government is detaining families for less time, releasing them in three weeks or less to pursue their asylum claims in immigration court.

Chris Cabrera, the vice president of the National Border Patrol Council, the union for Border Patrol agents, told The Daily Signal that immigrants from Central America seem to be responding to the new detention procedures.

“I would say it’s a major reason we’re having the surge because people know we won’t detain them and are going to release them,” said Cabrera, who is a Border Patrol agent stationed in McAllen, Texas.

Cabrera said the women and children usually seek out the Border Patrol, rather than hide from them, to ask for asylum protection. He said nearly all of them are claiming they have a credible fear of returning to their home country.

Cabrera contends that the extra resources required to process the women and children leave officers without the manpower to secure the border, although the Texas National Guard is still patrolling the Rio Grande Valley in an extension of a mission that began last year.

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, a Republican, has also ordered the Texas Department of Public Safety to increase its patrols at the border.

“To say this is the new normal is the wrong answer,” Cabrera said, responding to officials who have referred to the surge this way. “It’s an admission of defeat that this is what we should accept. I don’t accept it. This should not be the new normal, and we need to secure this area.”

In a move to bolster immigration enforcement, the Obama administration next year will begin to conduct a series of raids targeting Central American families who have come to the U.S. illegally since the beginning of 2014.

According to The Washington Post, Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents would target adults and children who have already been ordered removed from the U.S. by an immigration judge—meaning they did not qualify for asylum—for deportation. Most of these people likely came here during the 2014 border surge. More than 100,000 families from Central America have arrived in the U.S. since last year.

David Inserra, a homeland security expert at The Heritage Foundation, believes the Obama administration’s plan to deport certain Central American families is meant to disrupt the momentum of the latest surge.

“People see that a prior wave came to the U.S. illegally, and many of them have not been removed,” Inserra said. “That’s why I think the Obama administration is saying, ‘Something is off.’ When there is greater enforcement, you are discouraging more people from coming illegally.”

Immigration experts insist that the challenge is deeper than security.

“It’s hard to stop by just catching and deporting people,” Rosenblum said. “The answer in the long run is to help Central America fix itself.”

Seeking a more enduring solution, Congress and the Obama administration included $750 million in year-end spending to help Central American countries combat poverty, gang violence, trafficking, and government corruption, and to improve border security and social programs.

“You don’t take kids on a horrible, dangerous journey unless you feel there’s no choice,” says @MichelleBrane.

Michelle Brane, the director of the Migrant Rights and Justice Program at the Women’s Refugee Commission, called the aid to Central America a “positive step.”

She says two-thirds of Central American women with children try to flee internally before trying to come to the U.S.

“It’s a pretty grueling journey,” Brane said. “A lot of people are saying, ‘Why would a mother put their child through that?’ Look, I am a mom. You don’t take kids on a horrible, dangerous journey unless you feel there’s no choice.”