In one of his calls to action for Congress after the terrorist attack in San Bernardino, Calif., President Barack Obama urged lawmakers to pass legislation preventing suspected terrorists on the no-fly list from buying guns.

So far, Republicans have voted down this proposal, just as they have rejected other gun control measures.

While Obama and Democrats frame the act of denying weapons to potential terrorists as a no-brainer, Republicans argue that such legislation would unintentionally harm the Second Amendment rights of everyday Americans.

That’s because, Republicans say, not everyone on the no-fly list, which is a component of the FBI’s terrorist watch list, deserves to be on there—which is especially unfair, they say, because people belonging to such lists usually don’t know they are on them.

In addition, opponents of using the no-fly list as a tool for gun control note that the two San Bernardino shooters, Syed Farook and Tashfeen Malik, were not on the list.

All of this raises the question: What is the no-fly-list, and the wider terrorist watch list, and why is it necessary?

According to one expert who helped oversee the terrorist watch list under Presidents George W. Bush and Obama, the list is necessarily secretive, involving unknown criteria that determine who gets put on it, which makes due process especially challenging.

“My view from the inside is that I think all of these complaints are valid, but I don’t see how else you can have a terrorist watch list,” said Timothy Edgar, who oversaw civil liberties and national intelligence issues, including the terrorist watch list, under the current and last administration.

If the list were handled more openly and terrorist suspects knew they were on it, Edgar told The Daily Signal, those people would likely try to use a different identity and hide their behavior.

“You always try to improve the process and make it more transparent, but the fundamental dilemma is that the process only works with a certain amount of secrecy,” Edgar told The Daily Signal. “I don’t see a way to get around that problem unless we get rid of the list. And most people would think that’s a bad idea.”

Established in 2003 in response to the 9/11 attacks and to criticism that intelligence agencies were not sharing information well, the FBI’s Terrorist Screening Center maintains what is commonly known as the terrorist watch list.

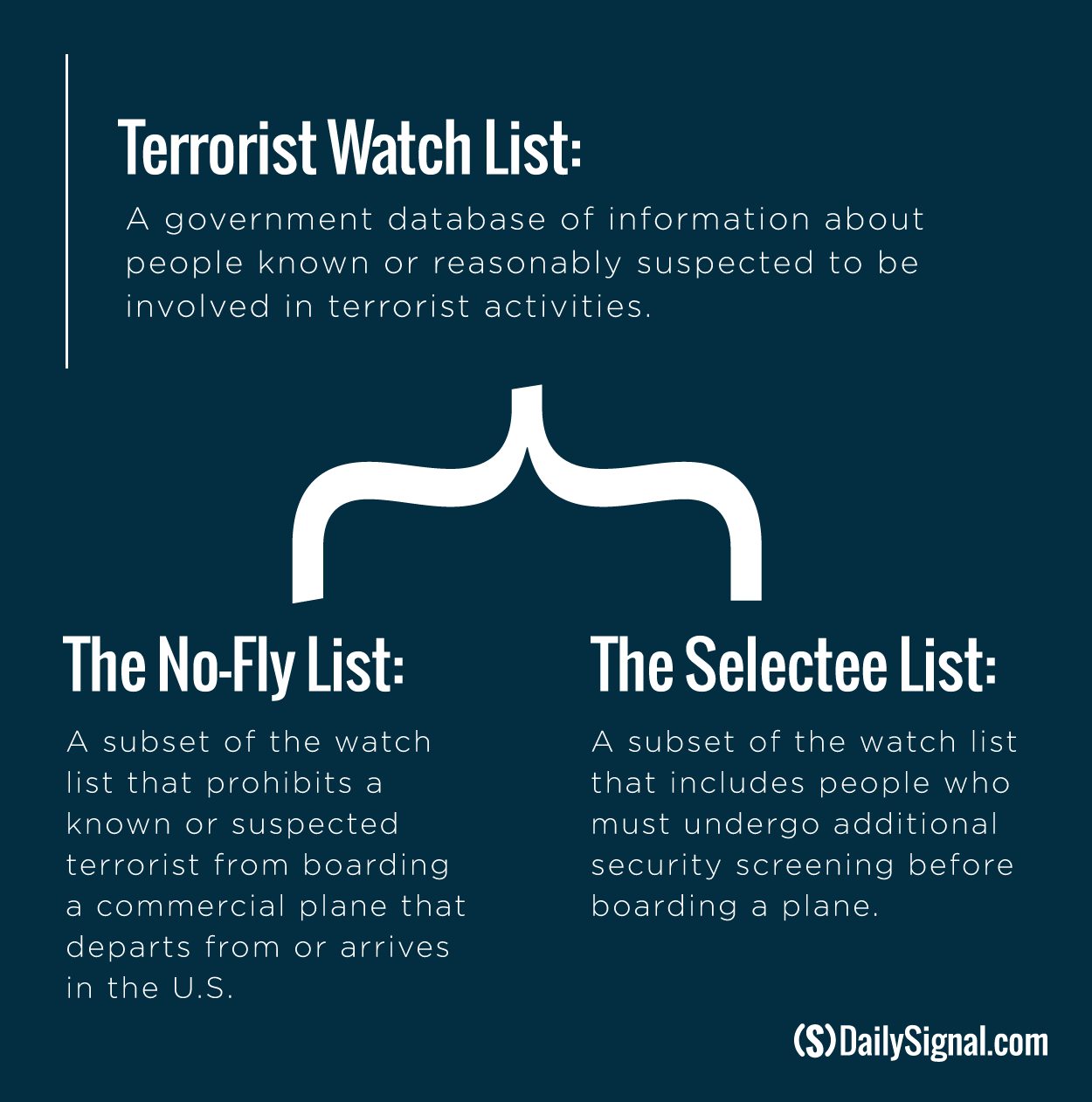

The terrorist watch list is a consolidated database of information about people known or reasonably suspected to have engaged in terrorism or related activities. The no-fly list is a subset of the terror watch list.

The FBI keeps private the watch list’s size, but according to a 2011 FBI fact sheet uncovered by Politifact, there were 420,000 members at the time. About 8,400 of those were American citizens or legal residents. The no-fly list had 16,000 names, with 500 of them being American.

The Intercept, a news organization that obtained classified government documents, reported last year that more than 40 percent of the 680,000 people on the terrorist watch list as of 2013 were described as having “no recognized terrorist group affiliation.”

Edgar, who is now a visiting fellow at Brown University, says most of those on the watch list, even today, are foreigners.

“The vast majority on this list are non U.S. citizens,” Edgar said. “That makes an enormous amount of sense. That’s where the most amount of terrorism is.”

People are notified they are on the no-fly list only when they arrive at an airport and are told they can’t fly. In the past, the government did not have to confirm or deny someone was on the list–even though it was obvious to that person when he was stopped from flying.

Those who are on the broader terrorist watch list—and not the no-fly list—are not notified of anything.

A 2010 lawsuit by the American Civil Liberties Union, a leading critic of watch lists, resulted in the government earlier this year agreeing to officially confirm to people who are stopped from flying that they are indeed on the no-fly list, and, in certain cases, like if the reasons are unclassified, to tell them why.

Under what’s known as the “redress” process, a person looking to get off the no-fly list can file a complaint to the Department of Homeland Security, which will work with the FBI and other intelligence agencies to re-examine the person’s record.

“The reason it’s hardly ideal for due process is because everything that happens is behind closed doors,” Edgar said. “There is not a hearing or anything like a normal process that would be transparent to the person complaining.”

“The reason it’s hardly ideal for due process is because everything that happens is behind closed doors,” @Timothy_Edgar says of the no-fly list.

In the past, especially when the list was first created, people would erroneously be included for having the same or a similar name as legitimate terrorist suspects.

That problem mostly impacted people with Arabic names, but it also affected those who share common English names belonging to members of the Irish Republican Army.

Edgar contends that the name problem has been mostly resolved because the watch list now includes other identifying information, such as a person’s birth date or passport number.

Still, not everyone is satisfied. The ACLU has an active lawsuit challenging the no-fly list, with oral arguments having occurred Wednesday. The ACLU is arguing that the FBI’s revised attempts at making a fairer due process are not good enough.

“The government puts people on the no-fly list using vague and overbroad standards, and it is wrongly blacklisting innocents without giving them a fair process to correct government error,” said Hina Shamsi, director of the ACLU National Security Project, in a statement to The Daily Signal. “Our no-fly list lawsuit seeks to establish a meaningful opportunity for our clients to challenge their placement on the list, which is error-prone and has had a devastating impact on their lives.”

Even as it questions the constitutionality of the no-fly list, the ACLU is refusing to take a position on the proposal by Democrats to block members of the list from obtaining weapons.

Edgar, meanwhile, argues that if you accept the terrorist watch list as necessary and effective at preventing terrorism, as he does, than it makes sense to apply the same restrictions to buying a gun as the government currently does to people wanting to fly.

“I sort of find it astonishing that someone would advocate the idea that the government can block somebody from boarding a plane, but it’s perfectly OK to allow somebody to buy a powerful weapon,” Edgar said. “That to me seems completely nutty, and I don’t see any rational argument to how that state of affairs makes sense.”

A report to Congress from the Government Accountability Office this year revealed that from 2004 to 2014, more than 2,000 people on the terrorist watch list were able to buy guns from dealers in the U.S.

The FBI is notified when a background check shows that a person on a watch list tried to buy a weapon from a gun dealer, and agents use that information to enhance surveillance on suspects.

Edgar says that automatically keeping people on watch lists from buying a gun would present difficult questions.

“If you extended the terror watch list to gun purchases, there will be the same issues you have with flying and traffic stops; if there’s an encounter, what do you want the gun salesman to do?” Edgar said.

“I personally think given the threat of this person committing a mass shooting tomorrow, if I were the FBI, I’d say, rather than let the gun purchase go through, let’s stop it, even if we tip him off because we’re stopping a mass shooting.”

Rep. Justin Amash, R-Mich., is a leading opponent of the no-fly list because he believes it infringes “on our rights without due process.” (Photo: Kevin Lamarque/Reuters/Newscom)

Those making the argument against the effort to stop members of the no-fly list from buying guns have mostly focused on their problems with the list itself rather than the idea of preventing terrorists from getting weapons.

“The government may not infringe on any of our rights without due process,” said Rep. Justin Amash, R-Mich., in a statement to The Daily Signal. “People are added to the president’s no-fly list on the basis of secret criteria, without trial and the ability to confront the accuser, and without conviction. This list and others like it are unconstitutional.”

Amash was a leading critic of the National Security Agency’s bulk data collection program, which ended this month.

But like defenders of the NSA program, Edgar says the no-fly list, and its undoubtedly secretive process, is a necessary evil in a time of complex terrorism threats.

“The lists are a little unfair, or a lot unfair, but this is a part of the new normal of post-9/11,” Edgar said. “We do the best we can to give people some limited rights to get off those lists, and we have succeeded in doing that to a certain degree—better than we did when we first started under the Bush administration. We should continue to make it as fair as possible, given the constraints we have.”