Our two greatest presidents, George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, respectively thought Thanksgiving sufficiently important to initiate its national celebration and to later revive this tradition.

Our accepted convention is that Thanksgiving is about family togetherness and feasting. Surely this is part of it—but perhaps a more refined notion of what this nearly ancient holiday should mean for us today is helpful.

National days of reflection are required to unify the American public in common sentiment. Washington had this in mind in issuing his rightly famous Thanksgiving Day proclamation of 1789.

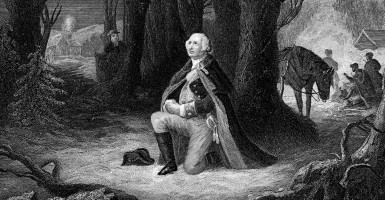

First begun as a harvest holiday, Thanksgiving predates the founding of our republic. But in this first proclamation of the first year of his presidency, Washington gave a political direction to the holiday. As he said elsewhere, he wanted, through his example, “to establish a national character of our own.”

In doing his part to establish our national character, Washington was aware that we are a people capable of courage and assertion, able to win independence. He was likewise aware of our ability to choose, through representatives, a new constitutional order.

Progressivism’s quasi-religion lacks any understanding of gratitude and humility.

But this holiday is of a different character, as it calls us to develop a capacity for gratitude. The American public ought to be grateful not merely, however, for the immediate circumstance of their lives, but also for the greater blessings of liberty bestowed upon their nation. Our gratitude is directed toward a nonsectarian God—like the God of the Declaration of Independence—which all citizens can worship.

Importantly, gratitude also means acknowledgement of our frailty and the imperfection of our understanding; gratitude implores us to deepen our self-knowledge. Thanksgiving is, therefore, a holiday against self-satisfaction and pride.

At the end of the Proclamation, Washington implores Americans toward modesty regarding our own powers, reminding citizens that we live in an order that may be mysterious insofar as God possesses superior knowledge of what is “best.”

But are all peoples capable of gratitude? In the present time it has become fashionable to espouse if not open atheism, then at least antagonism toward religion. These opinions come forth in various, sometimes obfuscated, forms.

Part of the left’s recent fanaticism originates from the fact that progressivism’s quasi-religion lacks any understanding of gratitude and humility. Progressivism precludes belief in these since progress as an alleged cosmic force is neither merciful nor beneficent, but is merely abstract and all-powerful. As such, it does not encourage its believers toward either humility or gratitude.

Neither does belief in the abstract and inhuman forces of progress require humility on account of human frailty and ignorance. Rather, progress, claiming perfect knowledge of the laws of the universe, leads to fanaticism.

Is the individual, modeled on these assumptions, of the kind required for self-government? Rather, does not self-government require generosity between citizens, which can be the product only of a common recognition of an America inhabited by one people, united in a common cause, with common beliefs, grateful for what has come before us?

What happens to a people when they lose the ability for gratitude? Insolence and impudence rule, while the various factions devour each other, competing for the national stage. Alternatively, one might inquire whether a people is up to the task of ruling itself once gratitude is lost, since then it loses its ideals and the justification for its self-government.

Our nation has produced hitherto-thought impossible prosperity on the broadest scale. “The civil and religious liberty with which we are blessed” has endured as an ideal for many generations. Indeed, many remarkable individuals have fought to secure these blessings for our benefit.

On Thanksgiving this year, perhaps raising our purview above the pleasures of family togetherness, we might think about our nation, the good fortune we have to be its citizens, and the task ahead in preserving it.