The Obama administration and its negotiating partners have described their nuclear deal with Iran as the best way to prevent Tehran from getting a bomb over the next decade.

But recent events have raised questions about another issue not covered in the agreement: Iran’s aggression in the Middle East.

Indeed, Iran has shown no signs of retracting its meddling in the region since the accord was announced.

The newest concern comes from Israel, which is alleging that Iran sponsored rocket attacks into its territory from Syria last week.

According to Politico, Israeli diplomats filed a formal complaint with the U.S. and its partners in the July 14 nuclear deal, charging Iran with “an indiscriminate and premeditated terrorist attack against Israeli territory without any provocation.”

“This incident doesn’t surprise me in the least, because the Iranians have made no effort whatsoever to hold back since the deal was announced,” said Daniel Pipes, president of the Middle East Forum.

“It’s perfectly consistent with their extremely aggressive stance that they’ve always had.”

Max Abrahms, a Northeastern University professor and terrorism analyst, notes that while the United States is unlikely to be affected by Iran’s aggression, Israel faces a different reality.

“A country such as Iran would never threaten the homeland even if it develops a nuclear weapon,” Abrahms says. “But the threat matrix is a lot more complicated in Israel. Essentially Obama is saying, look, Iran isn’t so dangerous, it helps us in the war on terror. Israel is banging its head and saying, don’t forget Iran is the leading sponsor of terrorism.”

Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, attends a mass prayer in Tehran. (Photo: Ay-Collection/SIPA/Newscom)

In interviews with The Daily Signal, Middle East experts discussed the logic of this aspect of the Iran deal—that negotiators decided to focus solely on the nuclear issue and left out other issues such as terrorism and human rights abuses.

Pipes, who opposes the deal, says the agreement is a good one if viewed through the nuclear-only lens.

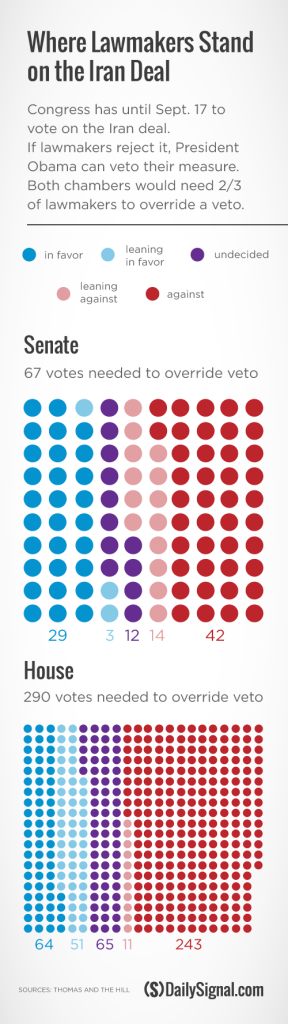

Earlier this month, 29 of the nation’s top scientists wrote a letter to President Obama praising the agreement for imposing “much more stringent constraints” than any previous nonproliferation framework.

But critics like Pipes say it’s impossible to separate the nuclear issue from Iran’s other ambitions.

“Of course you could have been a tougher bargainer who pushed on a whole range of issues, and demand all sorts of change,” Pipes said. “But that’s not what we have. Nothing else matters, and the Iranian regime gains in every other regard.”

Other observers of the deal argue that Iran’s support for terrorist groups such as Hezbollah and Yemen’s Houthi rebels occurred even when Tehran’s economy suffered under sanctions.

“Iran’s radical regime always has prioritized expanding its power and exporting its Islamist revolution over improving the economic welfare of its oppressed people,” says Jim Phillips, an expert on the Middle East at The Heritage Foundation.

Supporters of the deal say funding terrorism is not an especially expensive endeavor.

“It doesn’t cost that much to buy a lot of RPGs and AK-47s and to pad the coffers of groups of 5,000 fighters here and 10,000 there,” says Michael O’Hanlon, the director of research for the foreign policy program at the Brookings Institution.

Some $100 billion released to Iran after sanctions are lifted under the deal won’t enhance those aggressive activities, proponents believe.

“There is the argument by opponents of the deal that it will enable Iranian funding in Middle East,” says Alireza Nader, a senior international policy analyst at the RAND Corporation.

“But they can do that right now actually. It doesn’t take a lot of money for you to be influential in the Middle East. Because of the power vacuum and rise of sectarianism in the region, a lot of Shia groups are feeling insecure and seeking Iranian protection. Iran will continue to fill those opportunities, regardless if there is a deal.”

Northeastern University’s Abrahms argues that the U.S. could have used the negotiations as leverage to extract non-nuclear-related concessions from Iran.

“The terrorism sponsored by Iran is very relevant to the deal,” Abrahms said. “The deal entails enriching Iran with essentially no limitations in how it spends the money. Our recourse is very limited in terms of sanctions. It’s a real shame the deal is not more specific in regards to punishment. It is almost certain Iran will cheat, and we should not just be sure what cheating means, but what the response should be.”

No matter its relation to the nuclear deal, the decision by the U.S. and its negotiating team to sideline the terrorism issue showcases a broader trend that worries allies like Israel.

The U.S. is faced with competing problems in the region—from ISIS, the Sunni terrorist group, to the repressive Shia government of Bashar Al-Assad in Syria (supported by Shia-led Iran). This has forced the Obama administration to prioritize its resources.

The situation is made more complex by the fact that Iranian-backed Shia militias are leaders in the fight against ISIS.

“The U.S. has determined the radical Sunni threat as being more dangerous than the radical Shia threat,” Abrahms said.

Pipes contends it’s understandable for the U.S. to view the ISIS threat as the bigger issue, but Iran’s position as the main Shia actor of terrorism cannot be ignored.

“ISIS, because of its flamboyance and barbaric tactics, has won enmity that the Shia actors don’t have,” Pipes says. “But Iran is still a threat to the West too. Whereas ISIS just attacks people, willy nilly, without any larger organization or goal, the Iranians are strategic and more clever about their terrorism, so they hold back.”

Even if the deal is successful in containing Iran’s nuclear issue for a time, Tehran’s pursuit of terror isn’t going anywhere.

“This is the strategy we’ve chosen whether we can really pull it off or not,” O’Hanlon says of the U.S. handling the issues separately. “But in a sense, we don’t have a choice. They are interconnected problems, but they are distinct, and Iran is certainly following different strategies in those two domains itself, so we are going to have to try to reciprocate.”