When Nasrin Kholghy opened the letter from the city of Glendale, Colo., in April, it transported her back to another country in another time.

The letter notified Kholghy of an upcoming city council meeting.

There, Glendale’s leaders would be voting to approve the use of a tool that would give them the power to take Kholghy’s property and transform it into a planned retail, entertainment, and dining redevelopment project.

The news brought Kholghy back to Iran, the country she emigrated from alone in the 1970s.

“When I got the letter of them being able to use eminent domain, I really, really felt—we lost a lot of land in Iran when the revolution happened,” Kholghy said. “I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, it’s happening again. We’re losing it again.’”

Eminent domain is a power given to the government to take private property for a public use. In Kholghy’s case, the city had its eyes on six acres of property her family owned.

The property contains the family’s 30-year-old rug business, Authentic Persian and Oriental Rugs.

Last month, the city offered to buy the Kholghys’ property for $11 million. But the family rejected the offer, saying instead they wanted to remain in the community they’ve called home since Kholghy came to the United States 40 years ago.

“I have memories of our kids jumping on rug piles. They pretended the floor was lava,” Kholghy said in an interview with The Daily Signal. “We’ve had customers who’ve done that, and they bring their kids. The same person who jumped on the rugs, they bring their kids to jump on the rugs. It’s not like were just going to take this money and go away.”

Nasrin Kholghy looks at some of the rugs she sells at Authentic Persian and Oriental Rugs. (Photo: Nasrin Kholghy)

Humble Beginnings

It’s difficult not to smile when speaking to Kholghy about her start in the United States.

The oldest of five, Kholghy laughs as she remembers details about her younger years.

In her early 20s, when she was just getting started in the industry, Kholghy confronted and challenged a rug shop owner.

“I told him I would open a shop and ‘put you out of business,’” Kholghy recalls. “Sometimes you forget [those] things.”

The Iranian woman has had the same phone number since 1976—”nobody else has that long-running of a phone number,” she said—and still remembers the exact date she arrived in the United States from Iran: Jan. 6, 1975.

Kholghy traveled to the States with her mother, who returned to Iran a month later, leaving Kholghy alone to learn English in Trinidad, Colo., and pursue an American education.

Over the next four years, Kholghy settled into her life in the United States. She got married to her husband, Mozy Hemmati, at the close of 1975, and the couple graduated together from the University of Colorado Denver four years later.

After graduation, Kholghy and her husband decided to remain stateside, as the revolution in Iran had broken out while they were in school.

By 1979, three of Kholghy’s four siblings had joined their oldest sister in the United States, and they all lived together in a home in Glendale, Colo., which the family still owns today.

>>> Houston Churches Sue City for Trying to Take Their Private Property

Then, 52 Americans were held hostage in Tehran, and it became impossible for Kholghy’s parents to send their children money.

But Kholghy’s dad found a way to help his kids.

“My father called and said, ‘The only thing that Iran is letting out is rugs, so I’m going to send you guys some rugs, and then sell them and eat and go to school and pay tuition. Just use it,’” Kholghy recalled.

When the first rugs arrived from Iran, Kholghy tried to sell them to other stores.

She opened the Yellow Pages, found the largest ad for rugs she could find and made an appointment. But after a bad experience with the store’s owner—the same man she vowed to put out of business—Kholghy found herself outside of an empty storefront in the Cherry Creek Shopping Center.

The building was set to be demolished, and management told Kholghy they were no longer leasing.

She offered to lease the space for just one day, one week, one month—the amount of time didn’t matter—so long as Kholghy had a place to sell the rugs her father had sent from Iran.

Kholghy’s pleas worked, and she began leasing the space.

“We didn’t even know what they were worth,” she said of the Persian rugs her father sent. “We just sold them for whatever people paid for them.”

Now more than three decades later, what began as a temporary way for the Kholghy’s to pay their college tuition has grown into a full-time business, Authentic Persian and Oriental Rugs.

“Oh, my God, we got lucky,” Kholghy said, looking back at how her business began. “People came.”

Adding To the Land

For the last 25 years, the Kholghys have been running their business on roughly an acre of property located on one of the busiest streets in the Denver area.

The family runs the store together. In 2006, they officially purchased their property and the adjacent five acres of land, which they now lease to a hair salon, marijuana shop, car dealership, and detail center.

“We’ve always had a feeling that this area could be much nicer, better, with more stuff,” Kholghy said. “We thought of adding little things to the land.”

In 2007, the family decided to put together a plan to spruce up their property, drafting a redevelopment plan that included 11 condominiums on top of two stories of restaurants and shops, including their own store, Authentic Persian and Oriental Rugs.

The Kholghy family attempted to work with the city to redevelop the property they own in Glendale, Colo. The city rejected their plans and unveiled their own proposal that didn’t include Authentic Persian and Oriental Rugs. (Photo: Nasrin Kholghy)

It was Kholghy’s dream to live in one of the condos overlooking the business she built, which she knew her own children would take over eventually.

“I had in my head that when I retire and I’m old, I can be upstairs and still watch over [the family],” Kholghy said.

The family submitted the plan to the city, which considered but eventually rejected it.

“After talking back and forth with them, it became apparent they weren’t going to let us do anything we wanted,” Kholghy said. “They’re going to find a way to say no.”

>>> Dreams Demolished: 10 Years After the Government Took Their Homes, All That’s Left Is an Empty Field

‘It’s Happening All Over Again’

Just before the city of Glendale sent the Kholghys the letter notifying them about the potential for condemnation, officials unveiled Glendale 180, “a dining and entertainment development that reestablishes Glendale’s position as the essential social hub of the Denver area.”

The 42-acre project is projected to cost $175 million and, according to a map of the proposed site released by the city, is situated on property that includes the land the Kholghys own.

After unsuccessful negotiations, the Glendale City Council voted in May to give the city’s Urban Renewal Authority the power to use eminent domain for the Kholghys’ six acres of land.

“I felt like it’s happening all over again, and I felt what my father must’ve felt when they took all his land in Iran,” Kholghy said.

The city is projected to break ground this fall. A city official declined to make Mayor Mike Dunafon and members of the city council available for interviews because of pending litigation.

The city unveiled a plan for Glendale 180, a dining, entertainment and retail space, in April. That same month, Glendale officials sent Nasrin Kholghy a letter letting her know the city council would be voting to approve the use of eminent domain to take her property. (Photo: Glendale 180)

Post-Kelo Takings

The last clause of the Fifth Amendment, the Takings Clause, gives the government the power to condemn land through eminent domain if it satisfies two conditions: first, it’s for a public use, and second, the owner of the land must receive just compensation.

Historically, public use constituted the taking of property for a school, bridge, or road—an entity that benefited the public.

However, in 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court broadened the definition of public use in the controversial case Kelo v. City of New London. According to the high court’s ruling, the government has the right to use eminent domain to transfer property from one private party to another private party for economic development so long as just compensation is provided.

The ruling became one of the most despised in the court’s history.

In the wake of the Kelo decision, more than 40 states passed laws limiting the use of eminent domain for transfers to private parties. In 11 of those states, the legislature passed constitutional amendments.

Immediately following the Kelo decision, reports of local and state governments’ using eminent domain for private-to-private takings died down.

Now, a decade after the Kelo case, Paul Larkin, a senior legal research fellow at The Heritage Foundation, said he believes municipalities will begin exercising their eminent domain power for such condemnations once again now that public pressure has eased some.

“There have been so many developments in the law, so many developments in life and so many developments in politics since [2005] that it’s fair to say that this issue, which captivated the American public back 10 years ago when the Kelo decision was decided, now has dropped precipitously in the ordinal ranking of important issues,” Larkin said in an interview with The Daily Signal. “So it would surprise me for cities and states not to start to do this again.”

In the Kholghys’ case, the city voted to use eminent domain to transfer their privately owned property to another private party, who would then redevelop the land and build the restaurants and entertainment for Glendale 180.

Prior to approving the use of eminent domain to condemn the Kholghys’ property, the city conducted a study in 2013 to determine whether the area is “blighted.”

According to the survey, a “blighted area” is one that “substantially impairs or arrests the sound growth of the municipality, retards the provision of housing accommodations, or constitutes an economic or social liability, and is a menace to the public health, safety, morals or welfare.”

Additionally, for an area to be deemed “blighted,” it must satisfy at least four of 12 factors identified by the state, which range from “slum, deteriorated, or deteriorating structures” to “unusual topography or inadequate public improvements or utilities.”

For a municipality to legally invoke eminent domain, a property must be deemed “blighted.”

After the 2013 study, the city said Authentic Persian and Oriental Rugs constituted a “blighted area.”

“Your business is what gives you sustenance,” Larkin said. “Business allows you to buy the house. Business allows you to provide groceries for the people who live there. The business allows you to provide a commodity that the community desires, and it gives you a place in the community as a respected businessperson. If they take your business away, they are essentially taking away that part of not simply what gives you sustenance, but also your identity.”

>>> Commentary: The Two Key Mistakes the Supreme Court Made When Deciding Kelo

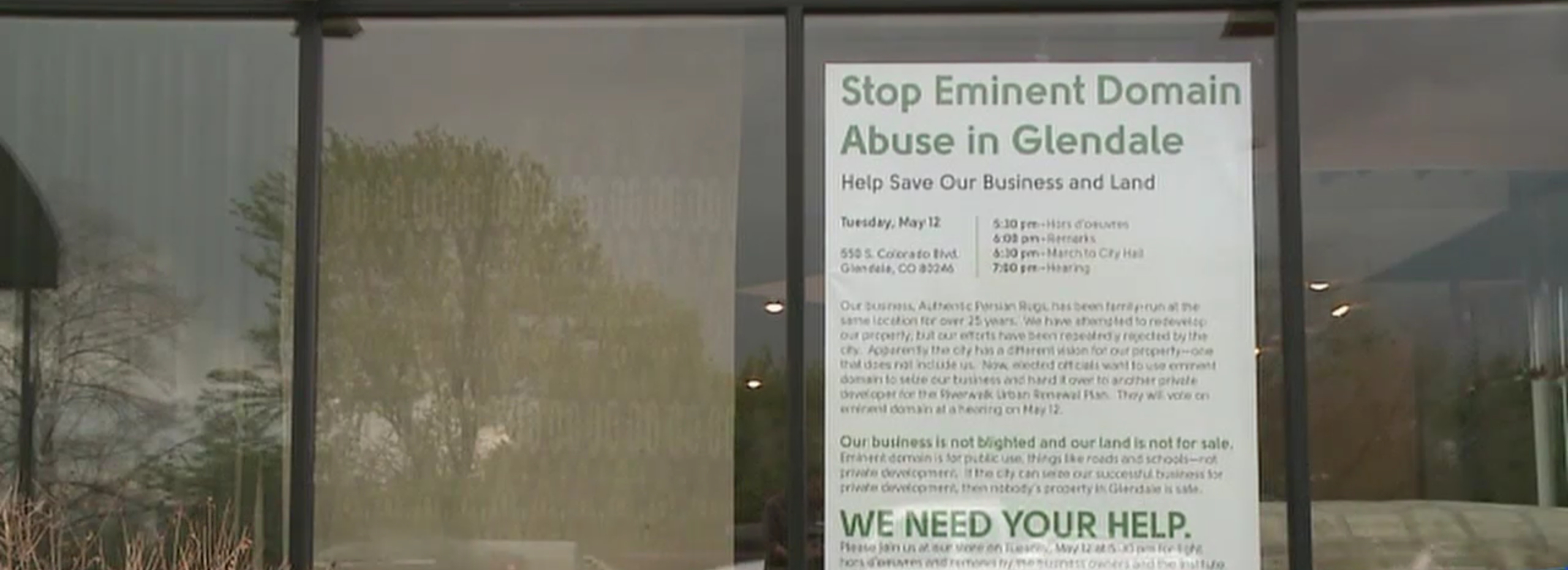

A sign posted in the window at Authentic Persian and Oriental Rugs calls on customers to protest the use of eminent domain in Glendale, Colo. (Photo: Screenshot/Fox News)

‘In Limbo’

Late last month, Glendale offered to buy the Kholghys’ six acres from the family for $11 million and gave them several days to make their final decision.

The family turned it down, insisting they wanted to stay in the same location they had been for the last 25 years.

“The most important thing to us is being here and having the shop here,” Kholghy said.

The offer was millions less than a previous bid the city made in 2012, for $19 million, which the Kholghys also declined. The city, Kholghy suspects, was well aware that the family would decline their July proposal.

“If you said no to $19 million, why would we say yes to $11 million? They knew that,” Kholghy said. “I think they just said that to get the media and public pressure off of them.”

After the family denied the offer, the city issued a statement saying they would move forward with redevelopment without the Kholghys’ property.

“We were prepared and excited to proceed either way,” said Dunafon, the Glendale mayor, in the statement. “But now that the path forward is clear, things will really kick into high gear.”

Linda Cassady, Glendale’s deputy city manager, told The Daily Signal the city’s Urban Renewal Authority “doesn’t have any intention of condemning the property.”

“If we did that, it would be a really unfortunate thing for Glendale, and we really don’t have any intention to do that,” she said.

Kholghy, though, isn’t convinced.

The city has said they won’t use eminent domain for the Glendale 180 project and won’t remove the property’s “blighted” designation, which is legally required to use eminent domain.

“They say, ‘We will not use condemnation for this project,’” she said. “You will use it for another project. They leave themselves open to do what they want at any time.”

When asked if the city will re-examine whether the area is blighted, Cassady said the onus is on the Kholghys to “cure the blight.”

Larkin says the Kholghys are right to be skeptical.

“From what I know, everything the city has done is fully consistent with an effort to be able to argue in court, were they to take that property, that they have acted with entirely benevolent motives of protecting the property, by advancing the community’s welfare,” he said.

“I don’t think these people are out of the woods yet,” Larkin continued. “After all, unless and until the city quite affirmatively says ‘we will not take your property,’ they can always walk back from anything they’ve said before. Even more so, even if they were to say ‘we will not take your property,’ that doesn’t prohibit other political officials from changing their mind in the future.’

Kholghy said she just wants to know her property will be safe from condemnation.

“We don’t want to fight. We don’t want to be in limbo,” Kholghy said. “You want to go on with your life. You want to know what to plan for. Life is hard as it is without thinking what’s going to happen in the next day or so.”

>>> Commentary: Thanks to This Supreme Court Decision, The Government Could Seize Your Living Room