For years, Kirk and Tanya White thought New Orleans public schools didn’t work for their two sons.

They got their eldest son, Geno, into a private school under a city education initiative, but his father says it turned out the new school also was failing by Louisiana’s own standards.

Then Geno hit a low point when he was robbed of his cell phone after he got off the bus one day in his school uniform. After that, he no longer was excited about school.

“He didn’t want to get on that bus anymore,” Kirk White recalls in an interview with The Daily Signal.

“He’s a tough kid,” White adds. “But when it comes down to that type of lifestyle, that really bothered him. He didn’t want to get in conflict.”

But the education initiative turned the page for Geno when, entering high school, he was able to find another school that met his needs.

Although Geno, now 16, got off to a rocky start in the program, it gave the family the money—and power—to find a school that worked for him.

It now is going so well that the Whites enrolled their younger son, Kole, now 10.

The program, Kirk White says simply, “got me my son back.”

The Louisiana Scholarship Program

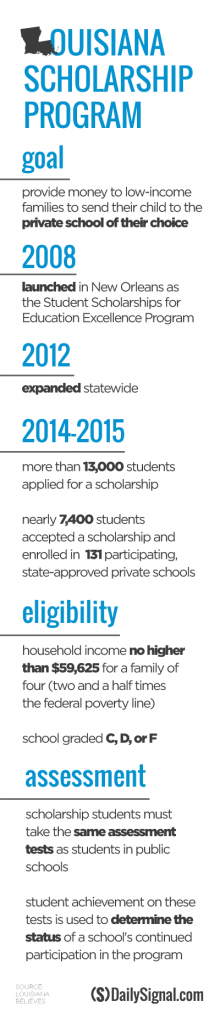

At first called the Student Scholarships for Education Excellence Program, the initiative launched seven years ago in New Orleans.

Its goal was to provide the city’s low-income families with the same opportunity more affluent parents already had: the ability to send their children to a school of their choosing—and not be trapped by their ZIP code.

In 2012, the program expanded statewide as the Louisiana Scholarship Program.

Many residents of the state, which had become infamous for having some of the worst-performing schools in the country, embraced the new attempt at education reform.

Others were skeptical or outright hostile, viewing it as an attack on public schools and teacher unions.

Today, nearly 7,400 students are enrolled in the Louisiana Scholarship Program and have chosen to attend one of 131 participating non-public schools.

To be eligible, a student must come from a family whose income is no more than two and a half times the federal poverty line—which means it does not exceed $59,625 for a family of four.

The student also must be entering kindergarten or enrolled in a public school that has been graded C, D or F. (Since 1999, schools in Louisiana have been given letter grades designed to communicate the quality of performance to parents and the public.)

Kirk and Tanya White, lifelong residents of New Orleans, were only two of thousands of parents whose children qualified.

“Before, we were being cheated of a lot of things we see now,” Kirk White says. “One of those things was education.”

Geno and Kole

Until he was accepted by the scholarship program—also known as a voucher system—Geno was struggling academically and socially. His parents were worried.

White, a truck driver, says he had planned on making enough money to send his sons to private school. A diagnosis of multiple sclerosis, or MS, got in the way.

In 2010, when he was diagnosed with the disease, White was forced to quit his job. That left the family dependent on his wife’s modest salary as a nurse at a local hospital.

“It put a damper on our whole world,” he says of the MS. “I thought I was going to be a great provider.”

Through word of mouth, the Whites also heard about the city’s new school voucher program in 2010. They put in an application for Geno that same year.

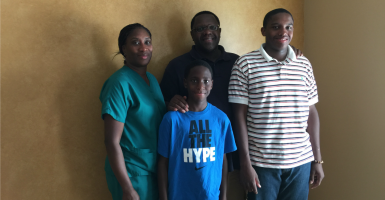

Geno White, 16, is entering 10th grade this fall. His brother, Kole, is 10 and entering fifth grade. (Photo: Kelsey Harkness/The Daily Signal)

Geno picked Life of Christ Christian Academy, where annual tuition normally is around $8,500. The scholarship program covered it in full.

When the Whites first toured the school, Geno’s father says, they “saw a different side to him.”

When talking about his first day at Life of Christ, Geno’s eyes light up.

“I finally had a locker,” he says.

At his old school, Geno had a cubby that he says could “barely” hold his books.

But after the robbery, the Whites decided their son had outgrown that school. Under the voucher program, Geno began his freshman year at Lutheran High School in Metairie, La., where he has been happy ever since.

The Hurdles

Although the Whites and other families quickly embraced the scholarship initiative, the program at first faced an upward battle with state and federal officials.

Teacher unions and their political allies regarded voucher programs as “taking money” from public schools and directing it to private schools. Proponents noted that per-student spending in public schools did not decrease as a result.

In 2013, the U.S. Justice Department brought a legal challenge to Louisiana’s voucher program. If the agency prevailed, the Obama administration would force thousands of low-income children–including Geno and Kole—to return to public schools.

Fully 90 percent of the children enrolled at the time were minorities who came from schools that had been graded D or F. If these children permanently left the public school system, the Obama administration argued, it would upset racial balance.

Gov. Bobby Jindal, who is now seeking the Republican nomination for president, fiercely defended the Louisiana Scholarship Program. Jindal invited President Obama and then-Attorney General Eric Holder to meet families such as the Whites.

“I believe if you and the attorney general are able to hear firsthand from parents about the experiences their children are having in the program, then you will reconsider the suit,” Jindal wrote in a letter to Obama. “I think it is only right that you and Attorney General Holder join me and come visit a scholarship school in Louisiana to look into the faces of the parents and kids and try to explain to them why you want to force them back into failing schools.”

The Justice Department’s argument soon was debunked by a state analysis of the program, which found it did not affect, and actually improved, desegregation efforts.

In November 2013, the Obama administration abandoned its lawsuit.

Looking Ahead

In the case of his sons, Kirk White believes that the Louisiana Scholarship Program more than pays for itself.

“If you don’t pay for school, somewhere down the line crime will come up…you will pay for jail,” he says. “It’s a win-win situation.”

As for its success?

“The proof is in the pudding,” White says, referring to his sons’ grades and athletic achievements. “They’re excelling in all areas.”

The Whites, like 91.9 percent of the 1,731 parents who responded to a recent survey, say they’re “very satisfied” with the program.

“It’s literally saving lives,” White says.

The Whites attribute some of that success to the demands the voucher program puts on parents. Every year, Kirk and Tanya must complete 50 hours of community service, which they say they actually enjoy.

“I love that these schools demand parent involvement,” Kirk White, 46, says. “I don’t want nothing for free. If the opportunity comes where I can give, I enjoy it.”

Tanya White, 44, who volunteers for her sons’ Parent Teacher Organizations, says the voucher program has helped their family grow closer—and even in size.

“Putting in those service hours, you really become family,” she says of other parents of children enrolled in the voucher program.

Already, more than a dozen states and Washington, D.C., have incorporated scholarship programs into their education offerings. Most of those, however, limit eligibility to students with disabilities.

If school choice advocates have their way, vouchers ultimately will be available to everyone.

In the meantime, Geno and Kole plan to continue their success on the voucher program and have their sights set on college.

One day, Geno says, he wants to use his smarts to give back to other kids like himself, who are in need of a better education. Kole has his eyes set on a career in basketball.

To reach their goals, they’ll have to keep in mind the number-one lesson taught by their parents.

“School comes first,” the brothers both say with a smile.

This story has been modified to clarify the sequence of Geno’s enrollment in the program.