On the third anniversary of the death of famous Cuban dissident Oswaldo Payá, the Human Rights Foundation released a report suggesting that the Cuban government may have killed him.

In their legal report, the Human Rights Foundation highlighted the inaccuracies and inconsistencies in the Cuban government’s investigation into Payá’s death.

The report found numerous due process violations, “damning” witness accounts, a “grossly inadequate” autopsy examination and countless other pieces of evidence presented by the Payá family that were overlooked by Cuban officials.

“The power in Havana believed it was necessary to destroy my father,” said Rosa Maria Payá, the daughter of the late activist. “This report will be an important tool against the impunity of that power.”

Payá, the most prominent Latin American pro-democracy activist of the last 25 years, died alongside his fellow activist Harold Cepero in a car accident after the vehicle ran off a Cuban highway and struck a tree.

The Human Rights Foundation concluded that the “evidence, which was deliberately ignored, strongly suggests that the events of July 22, 2012 were not an accident, but instead the result of a car crash directly caused by agents of the state.”

Spanish national Ángel Carromero, who was driving the vehicle, insisted that the car was rammed from behind by a vehicle with state license plates, causing the car to spin out of control and run off the road.

Carromero was immediately taken into custody after the crash and was forced to record a confession accepting guilt for the accident. Carromero was given a statement from the Cuban security officers that he was mandated to read on camera, and he subsequently participated in a rigged trial.

Carromero was sentenced to four years in prison for vehicular homicide. He later returned to Spain, where he retracted all of his statements that he was forced to make under duress.

The fatal flaw in the botched Carromero trial is a direct result of the Cuban judicial system, the Human Rights Foundation report found.

Cuba is a totalitarian dictatorship, and the investigation and trials looking into the deaths of Payá and Cepero were carried out in the expected authoritarian manner, the report said.

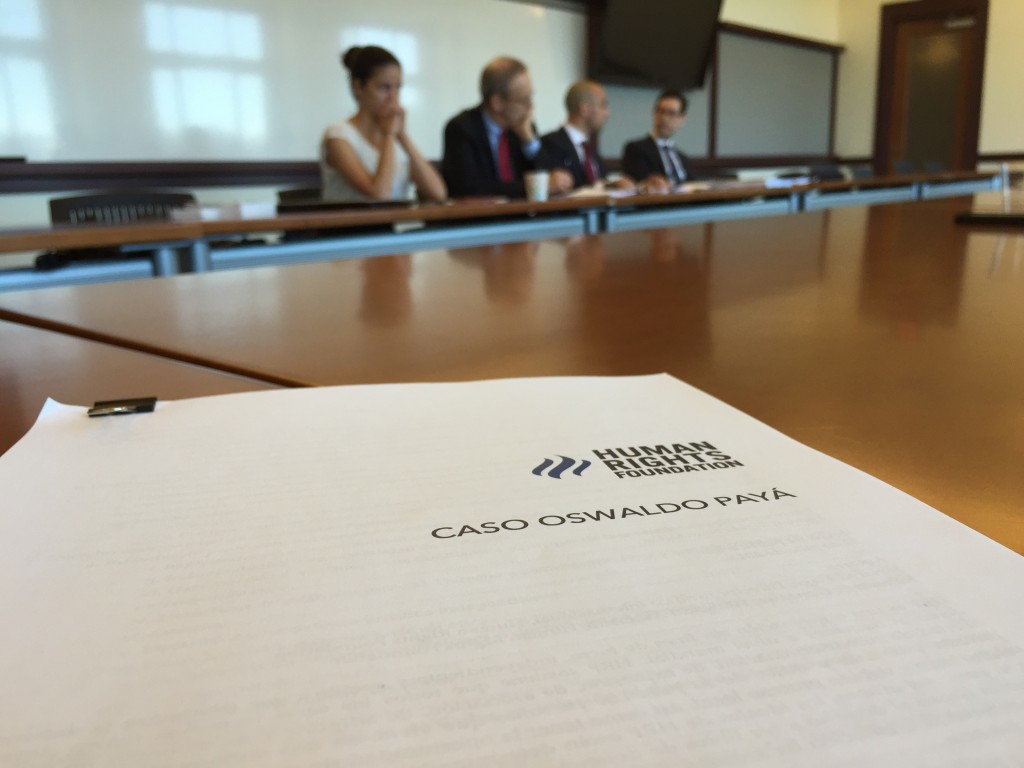

Javier El-Hage, general counsel for the Human Rights Foundation, presented the findings of the report at Georgetown University Wednesday. El-Hage explained that Cuban lawyers, unlike counsel in all other parts of the world, must defend the interests of the government, not the interest of their clients.

“When this happened on July 22, those who knew Oswaldo Payá said that this would’ve been like the South African government having murdered Nelson Mandela, or the Soviet government having done away with Andrei Sakharov, or the Burmese government having killed Aung San Suu Kyi,” said Carl Gershman, president of the National Endowment for Democracy, during a presentation of the report at Georgetown University. (Photo: Chelsea Scism/The Daily Signal)

Understanding the judicial system in Cuba is integral to understanding why Carromero’s trial and the investigation into Payá’s death was a sham, El-Hage explained.

All attorneys in Cuba have to register with a national guild in order to practice. The lawyers must abide by a code of ethics, legally compelling them to “consciously assume and contribute—within their duties—to defend, preserve and be faithful to the principles comprised in the nation, the revolution and socialism.”

Furthermore, their jobs should be done “imbued with the righteous, noble and humane ideas of socialism and inspired by the example set by the Commander in Chief Fidel Castro Ruz.”

As a result, the Human Rights Foundation report turns attention away from Carromero’s false confession and instead suggests “direct government responsibility” in the deaths of Payá and Cepero.

Specifically, the evidence suggests that the state agents were acting in one of three states of mind. Cuban officials were acting with the intent to kill Payá and the passengers, with the intent to “inflict grievous bodily harm” to them or with “reckless or depraved indifference” to their lives.

Each of these possibilities accounts for the state of mind necessary to be charged with murder in the eyes of international law, El-Hage said.