RICHMOND — It’s just after noon on a sunny, sweltering Tuesday in June. Roughly 15 inmates at the Richmond City Justice Center stand or sit on small, plastic chairs in a bright, sterile room on the fifth floor of the jail, waiting.

For most of the men in this over-50 group, waiting is a near-constant part of their existence: Waiting for trial; waiting for their public defender to call; waiting to see their new grandchild for the very first time.

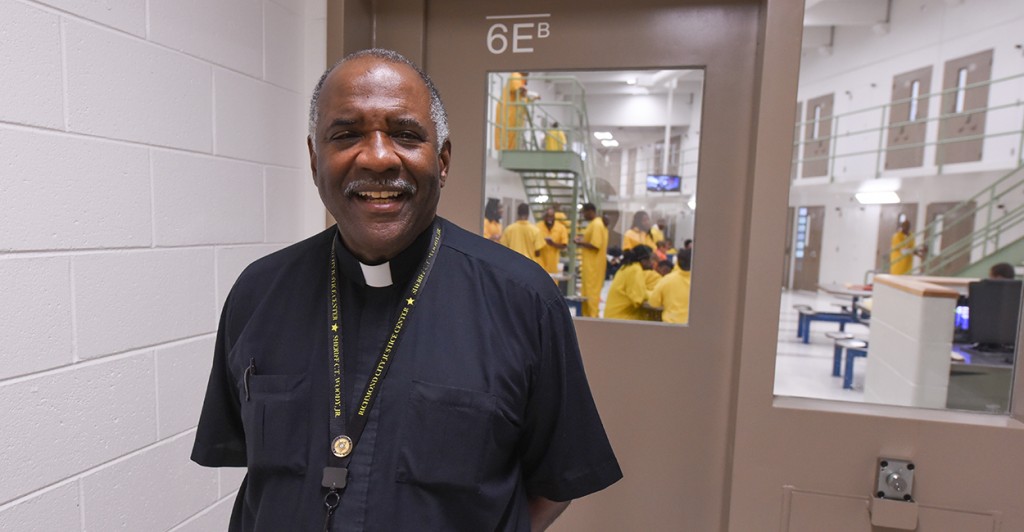

Their offenses vary, the scale of their transgressions reflected in the faded colors of their blue, orange, and brown jumpsuits. Feet tap, nails scratch against scalps and cheeks with anxious repetition, and every face turns as Father Alonzo Pruitt enters the room.

Pruitt, a 64-year-old retired Army First Lieutenant, greets the “residents,” as he calls them, with a quick hello. He apologizes for being late. His gentle nature hardens and his vocal patterns change ever so slightly, as though he’s putting on an invisible armor.

It begins to seem that his mere presence—with his kind face, dark, graying hair, and made-for-radio voice—almost impossibly sets off a few men. It’s nothing he’s done, he knows. He’s just often an outlet for frustration. It’s a role the Episcopalian Reverend Canon is happy to play, if necessary.

Before the hour is up, two men will have walked out of Pruitt’s fatherhood class—one after Pruitt calls his suggestion that parolees burn down probation offices as retribution “crazy.” Several others will be brought to tears as they quietly discuss the family that waits for them on the outside. Pruitt will prompt each man to verbalize one positive thought that will help them get through the next week.

After class, as the men file into the hall to return to their “pods,” the energy has shifted. It’s noticeably lighter. The men laugh more easily and aren’t bothered in the least when he asks them to pose for a photo—backs to the camera, of course.

“Something like one-and-a-half million black men are just missing from American society today, and were when I started doing this about eight years ago,” Pruitt says. “And missing meant they were either dead or in jail. Seems to me we need to do something to reach them where they are.”

Windy City Beginnings

If you asked a young Alonzo Pruitt what he’d grow up to be, chances are a jail chaplain and social activist are not that far off.

Born on the South Side of Chicago, Pruitt lived for many years with his parents and two older sisters in the Ida B. Wells public housing project, the first in the city to allow black residents.

His father, a committed churchgoer and mason, was a bus driver with the Chicago Transit Authority for 33 years. His mother taught English before becoming an assistant principal at a local public school.

Pruitt always felt drawn to activism. At 15 years old, he picketed a local A&P grocery store that was found to be selling old meat at higher prices in black neighborhoods.

By the time he reached Illinois State University, which he eventually dropped out of, he was campaigning for a homecoming “court” rather than a single homecoming queen, citing a need for African-American representation. At the time, the school of 20,000 had just 400 black students enrolled.

Sitting with him, while he rattles off a rapid-fire mixture of these stories and statistics, personal and national history blended as his mind jumps faster even than his voice might allow, his passion for people and social justice shines.

“One of the great dangers we suffer from in America today is just apathy,” Pruitt says. “Sometimes the problem seems so large, and our ability to do something about it so small. So you have to bloom where you’re planted, and just do the next right thing you can.”

Alonzo Pruitt sits in his office in the Richmond City Justice Center. (Photo: Clement Britt/The Daily Signal)

Pruitt eventually found his way to the Chicago Urban League, working as a community organizer before going back to school, receiving his Masters of Social Work, and going to work full time as a social worker. He did that for 13 years before he felt another calling.

Pruitt then studied at Seabury-Western Theological Seminary in Chicago, now known as Bexley Hall, and will very proudly tell you he belongs to the Episcopal Society of St. Francis and the Third Order (“The same order as Desmond Tutu!”).

Over the years, he’s held positions at many churches and also worked for eight years as an Army Chaplain. He specializes, it seems, in bringing spirituality to places that aren’t typically associated with God.

“I’ve always had this concern for the left behind, the left out, the overlooked,” Pruitt says, his voice almost musical. “My seminary professor once said that all of us really have one sermon in us, and the rest are just variations on that one theme. I think my theme is you really are loved, you really do matter, you really are important, you really can change … It’s fascinating to do the Lord’s work in a setting that’s not primarily about the Lord.”

Meeting ‘Mr. Homicide’

It’s that fascination with reaching those on the fringe of society that led Pruitt to write to Richmond Sheriff C. T. Woody, Jr., the man once known as “Mr. Homicide” for his ability to solve problematic murders in Virginia, shortly after the sheriff’s appointment in 2005.

“I’d never even met him,” says Woody, a bear of a man who, despite his grandiose kindness, remains intimidating. “He just sent me a letter. Requesting to come in here. He felt that he could better serve the community [here]. I finally met him, and he’s an amazing individual.”

Pruitt went to work for Sheriff Woody on a part-time, volunteer basis, bringing Bible study and counseling services to residents at the old Richmond Jail, which was torn down last year.

At the time, Woody was beginning to campaign for reform in Richmond, hoping the city would find the funds to build a new jail to replace a facility which, according to Woody, was plagued by rats, snakes, a lack of air conditioning, and busted windows that could not be replaced due to structural issues. Due to overcrowding, the 200 inmates on each jail tier were using two to three bathrooms. Inmates were regularly sleeping on the concrete floor.

“If you put bad people in bad conditions, what do you think is going to happen?” Woody says with a laugh. “And sooner or later, the majority of these people are going to get out anyhow. So who do you want: a better citizen or a better criminal?”

His lobbying proved effective when, in 2011, the Richmond City Council approved the building of a new, state-of-the-art, 430,000-square-foot facility dubbed the Richmond City Justice Center. It opened in 2014, cost an astounding $134 million, and is now one of the “newest, most innovative” facilities in the country, operating with a $30 million budget. The jail houses male and female inmates, both high custody and lower security, has an infirmary capable of dialysis, and over 400 cameras.

For his part, Pruitt now works full-time on staff at the Justice Center, overseeing a fleet of 86 volunteer chaplains. His team works to ensure that each pod of the jail is visited at least once a day and, despite the aforementioned budget, that inmates have access to things like books, Bibles, toothbrushes, deodorant, or shampoo when their state-allotted rations run out and they can’t afford to visit the commissary.

“Whatever your faith is, we have someone here to serve you,” Woody says, acknowledging Pruitt’s commitment to providing residents of all faiths with access to religious counseling. “[Father Pruitt] has been of tremendous value to morale, to violence being down, and to changing people’s lives.”

Pruitt also finds himself with the difficult task of coordinating trips to funeral homes to allow residents to visit deceased relatives, in addition to counseling guards and staffers who themselves sometimes struggle with life in prison.

“Somebody who studied the sociology of labor said that working in a jail or a prison is the second most stressful job in American society,” Pruitt says. “The only thing that’s supposed to be harder is being a coal miner. On any given day, you’re going to be cussed out, or have urine thrown at you, or somebody’s going to be furious with you for something you had nothing to do with.”

Breaking the Cycle

Pruitt’s personal history is indeed impressive—but as he’ll be the first to tell you, he’s still very much human. Despite four advanced degrees and two awarded religious titles, Pruitt has, for a long time, battled alcoholism, finally getting sober with the help of a 12-step program just over 20 years ago. He attends 12-step conferences whenever he can, like one in Atlanta earlier this month.

He’s honest about his struggle with addiction to an almost jarring degree (“Everybody who knows me knows I’m a drunk!”), and shares his journey with parishioners at Calvary Episcopal Church, where he says mass weekly, and with Richmond City Justice Center colleagues and residents.

“I feel very fortunate now to have escaped the mean streets as it were and, a day at a time, be winning the battle of addiction,” Pruitt says, needing to stop often as he walks through the jail to greet and hug colleagues who seem eager to say hello. “I think being open about my brokenness invites people to see that I’m not reaching down to them, I’m reaching across. We don’t have any groups in the jail in which somebody doesn’t have a problem with drugs or alcohol.”

Indeed, in class with Father Pruitt, he mentions his past alcohol abuse no fewer than two times, at one point encouraging residents to own the actions that got them locked up by explaining how he avoids alcohol altogether on account of his predisposition. His use of words like “shorty” and “tripping” only further this feeling of relatability. When residents volunteer information about their crimes, many are drug related.

Pruitt also prods reflection by asking residents how they can make better choices and avoid future stints in jail despite a roughly 67-percent recidivism rate nationwide. Though several men in the class — only four of whom have been in jail two times or less — challenge him throughout the session with cries of “You think you’re so holy” or “You don’t know what I’ve been through,” the nods and chorus of agreeable grunts that rumble throughout the room prove his candor effective. A 53-year-old named Tim resolves to get out of jail, and stay out, while lamenting about the jail’s directionless “young ones,” like his 19-year-old cellmate who refused to leave their room for two whole days out of fear of mingling with the general jail population.

It’s candor—and respect—that Pruitt has found most effective when working with inmates in Richmond.

“They’re not accustomed to being treated with respect,” Pruitt says. “They stand taller, or smile more, or say thank you in a way that makes you want to cry.”

‘If We’re Not Really Changing Them When They’re Here, They’re Coming Back’

Pruitt’s perhaps most proud of the work he’s done to recruit other volunteers, like Steve Harms, a man who works full-time yet visits the Justice Center each day on his hour-long lunch break. It’s a deal he’s worked out with his employer to foster a 25-year-long devotion he’s made to volunteering. Harms, a Presbyterian, leads a discussion-oriented Bible study group.

“I feel that the Lord has blessed me with a supportive family, a supportive church community, and this is my way of, you know, giving back and sharing with others the blessings that I’ve received,” Harms says. “Nobody is compelled to come [to Bible study], but those that they do are generally enthusiastic and willing to talk and learn.”

He’s worked with Pruitt over the last eight years as the Reverend’s established his Chaplaincy. “He’s the one who is kind of the bridge between the jail administration and the volunteers, expanding the opportunities for people to participate in faith-based activities,” Harms adds.

Despite establishing a solid network of volunteers, Pruitt does struggle with the transient nature of the Richmond City Justice Center, never knowing if he’ll have three weeks or three months to work with the men and women he counsels in classes and through one-on-one meetings before the Department of Justice calls on them—or if enough is being done to educate and rehabilitate inmates.

Lately, he’s focused on his work with Cross Over Health Ministries, an organization that provides residents a 12-week-long class on everything from diabetes to AIDS prevention. He’s also brought in a yoga teacher and partnered with Arts in the Alley, a group that paints murals and plans to pair female inmates with artists for therapeutic art sessions.

He tries to use his time, and encourages his volunteers to use theirs, to weave practical information into sometimes emotional encounters. He estimates he has contact with around 40-percent of the jail’s population, and often blends discussion with lessons on things like domestic violence or how to build positive self-esteem. Pruitt, who lost his wife to cancer several years ago, doesn’t appear to be slowing down anytime soon.

“There’s something like 120 sheriffs in the Commonwealth of Virginia, and a majority of them do not allow chaplains to minister in the jail as freely as our people do,” Pruitt says. “If we’re really not changing them while they’re here, they’re definitely coming back.”