Over the past 25 years, the Internet has gone from a relatively unknown arena populated primarily by academics, government employees, researchers and other technical experts into a nearly ubiquitous presence that contributes fundamentally and massively to communication, innovation and commerce.

China, Russia and a number of Muslim countries in particular have been open in their desire to limit speech on the Internet.

It is unsurprising that, as the Internet has expanded in importance, calls for increased governance have also multiplied.

Some governance of the Internet, such as measures to make sure that Internet addresses are unique, and that changes to the root servers are conducted in a reliable and non-disruptive manner, is necessary merely to ensure that it operates smoothly. That’s why it has been in place for decades.

>>> Read the Special Report: Saving Internet Freedom

A great factor in the growth and success of the Internet, from which nearly everyone has benefited directly or indirectly, is that governance has been light and relatively non-intrusive.

Some want this to change, particularly governments eager to enhance their control over the Internet content and commerce. They seek to assert international regulation and governance over the Internet far exceeding what is currently the case.

China, Russia and a number of Muslim countries in particularly have been open in their desire to limit speech on the Internet that they deem offensive or damaging to their interests.

Governments are able to control Internet policies within their borders, albeit with varying degrees of success. To expand these efforts for controlling Internet content globally, however, they must control the numbering, naming and addressing functions of the Internet.

This is hardly a new ambition for these nations. The United States has had to periodically rally opposition to similar efforts in the past.

For instance, the lead up to the U.N. World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) held in Geneva in 2003 and Tunis in 2005 sparked intense debate between the United States and other countries supporting a private-sector led model of Internet governance versus nations seeking to grant the U.N. supervision of the Internet.

At the 2012 World Conference on International Telecommunications (WCIT), Russia, China, and several other governments again sought to grant the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) greater authority and responsibility over the Internet. Countries dubious of ITU governance of the Internet, including the U.S., took an equally strong opposing position.

This debate has been temporarily sidelined by the March 2014 announcement by the United States that it would end its contractual relationship with the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) to manage the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) functions.

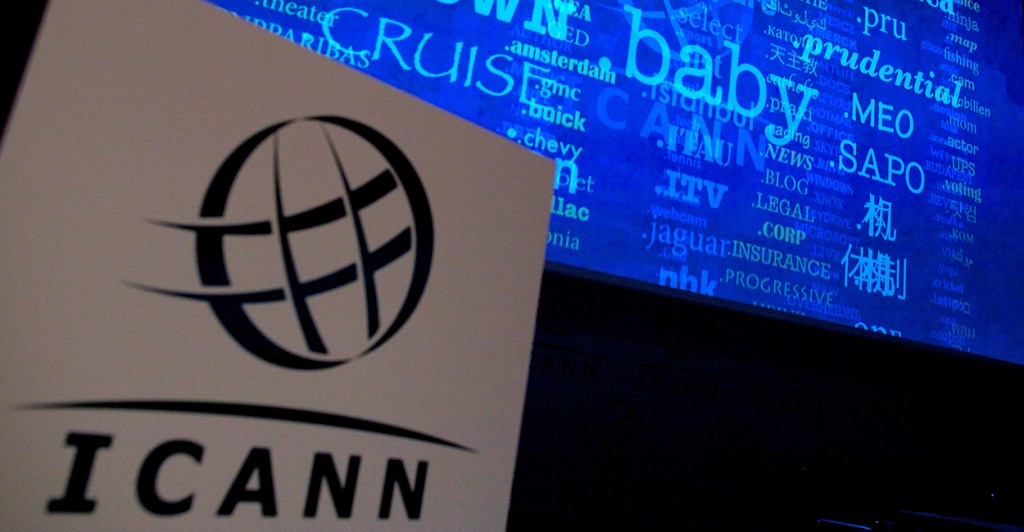

The IANA is critical to the smooth operation of the Internet through the management and global coordination of the Domain Name System (DNS) and the Internet protocol numbering system. The DNS is, in essence, the Internet address book that translates the alphanumeric name of a website (dailysignal.com) into the unique numerical IP address (72.21.81.133) that computers use to identify specific websites.

The U.S. federal government has expressed since the 1990s its intent to make management of the IANA fully private—that is, free from government oversight. However, this transition has been repeatedly deferred due to concerns over ICANN’s ability to fulfill its responsibilities absent U.S. oversight.

When it made its announcement, the United States made clear that ICANN would have to meet several conditions before it would allow the transition to occur:

- ICANN must continue to support and enhance the multi-stakeholder model;

- the security, stability, and resiliency of the Internet Domain Name System must be maintained;

- necessary reforms must be adopted to ensure that the post-transition ICANN would meet the needs and expectations of the global customers and partners of the IANA services; and

- the openness of the Internet must be maintained.

The United States also insisted that the U.S. role not be replaced by a government-led or an intergovernmental organization.

These conditions are fairly broad and much of the past year has been occupied by discussions between ICANN, the NTIA and the multi-stakeholder community (the various business, technology, and civil society groups that use and depend on the Internet) about what is needed to meet those conditions.

This is a critical matter.

When the U.S. government oversight role ends, ICANN will come under considerable pressure from a number of interested parties to adopt policies that they favor.

A rolling feed of ‘Generic Top-Level Domain Names’ applied for during a press conference hosted by ICANN in central London in 2012. (Photo: Andrew Cowie/AFP/Getty Images/Newscom)

It is critical that ICANN is sufficiently insulated from these pressures to make independent decisions while simultaneously being responsive and accountable to the broader multi-stakeholder community.

But we should not delude ourselves that a successful ICANN transition will resolve the debate over the future of Internet governance.

Ample opportunities exist in the future, particularly meetings of the ITU and other international forums on the Internet like the WSIS and the WCIT, for countries desirous of more direct government control of the Internet to press their agenda.

It is unclear how this dispute will be resolved. But the stakes are high.

If Internet functions and freedom are harmed or subjected to unnecessary regulatory burdens or political interference, not only would there be economic damage, but a vital forum for freedom of speech and political dissent would be compromised.