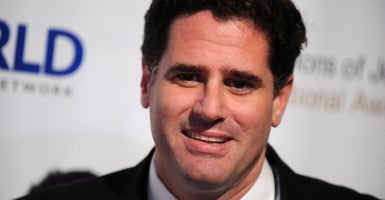

Ron Dermer, the Israeli ambassador to the United States, snapped his fingers to signify how quickly the Jewish state could go from being strong to vulnerable in the face of a nuclear Iran.

The same fragility can describe the current U.S.-Israel alliance at a time when the countries’ governments disagree over the best way to prevent Iran from obtaining a nuclear bomb.

In a speech meant to both reassure—and pressure—his country’s best ally, Dermer today tried to make the case that though his country disagrees with the Obama administration on the merits of an emerging nuclear deal with Iran, Israel and America share an unbreakable bond.

On the 67th anniversary of Israel’s independence, Dermer, speaking at The Heritage Foundation, said that the U.S.-Israeli relationship would live on eternally.

But at the same time, Dermer argued that the impending nuclear deal would threaten Israel’s survival and pit the U.S. not only against the wishes of the Jewish state, but also, of the broader Arab world.

“I don’t agree the [Obama] administration is on the other side of the moral divide [with Israel],” said Dermer, in response to an audience member who questioned the sincerity of the U.S.-Israel alliance.

“I think they have a different view of how to advance common objectives. But I don’t think they want to see a nuclear-armed Iran, I don’t think they want to make an agreement that they think will endanger Israel or make the region less secure. I’ve been in enough meetings with the president [Obama] to have a great deal of confidence that he’s sincere on his commitment on trying to create a safer and more secure region. We just have a disagreement on how that’s going to be achieved.”

Dermer, the American-born former Republican operative and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s right-hand man, offered Israel’s preferred alternative on how to deal with Iran’s nuclear program.

He said that Israel’s voice matters because it “has the most to lose” and the “most to gain” depending on how the U.S.-led negotiations with Iran are handled.

“We don’t believe the choice is war or to accept this deal,” Dermer said. “We believe the way to peacefully resolve this issue is to combine a credible, military threat of force with crippling sanctions.”

“That combination has not been deployed for 10 years,” he noted. “We had sanctions on Iran for a long time, but crippling sanctions only began in 2012. And within 18 months, Iran came to the negotiating table desperate to see those sanctions removed.”

‘Walk Into Nuclear Club’

In April, Iran and six world powers announced a framework agreement intended to curb Tehran’s nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief.

The details behind the framework agreement have been disputed by Iran and U.S. leaders.

But, from what’s known, the agreement would reduce Iran’s stockpile of nuclear fuel and its ability to produce new fuel; prescribe limits on its nuclear facilities; and establish an international inspection system.

Some issues, such as the timing of sanctions relief, and the process for ensuring compliance with the deal’s terms—and reimposing sanctions if the terms are violated—remain unresolved.

Dermer argues that whatever has been agreed to is not enough.

“What this deal does is it dismantles the sanctions regime and leaves Iran with its nuclear program essentially intact—albeit with constraints, but within about a decade those constraints are removed and Iran will have an industrial [nuclear] program tomorrow,” Dermer said.

Under the proposed nuclear deal, “Iran will walk into the nuclear club,” says @AmbDermer.

“Under this deal, Iran will walk into the nuclear club. The alternative to this is to hold firm, ratchet up pressure, and to not assume that what Iran won’t agree to today, they won’t agree to tomorrow.”

The U.S. has set a June 30 deadline for reaching final terms on a nuclear agreement with Iran.

Israelis and Arabs ‘On Same Page’

Israel’s concerns about the deal are shared by neighboring Arab states, who worry a relief from sanctions will free Iran to strengthen its support of terrorist groups and ignite a free-for-all nuclear arms race in the region.

“When Israelis and Arabs are on the same page, I think we should pay attention,” Dermer said to laughs from the crowd. “This is a unique moment in the history of the Middle East where the world as the Israelis see it and the world as the Arabs see it are lined up.”

“And I think not only should we stand together in confronting common threats, I think we should do whatever we can to try to seize the appetite of an alignment of interests to see if we can begin a broader rapprochement between Israel and the Arab world,” he added.

King Salman of Saudi Arabia (right) is one of many Arab leaders who are skeptical of the proposed nuclear deal with Iran. (Photo: Thaer Ganaim/APA Images/ZUMAPRESS.com)

Dermer went as far as to suggest shared interests with the Arab states over the nuclear issue could provide positive momentum for peace talks with the Palestinians.

“They used to believe the key to that [a rapprochement with the Arab word] was solving the Palestinian question, and there is no doubt that issue cannot be ignored,” Dermer said.

He continued:

“But as the prime minister said a few months ago, I’m not so sure the reverse won’t be true, meaning that I don’t know if Israel and Palestinian peace will unlock wider rapprochement with the Arab world. It might be broader rapprochement with the Arab world will unlock Israeli-Palestinian peace. We should be focusing the next few years on how we can take advantage of this historic aligning of interests between Israel and our Arab neighbors.”

Strong, Resilient

Netanyahu had seemed to throw water on the peace process—and over his commitment to a two-state solution—before his reelection in March when he said no Palestinian state would happen during his tenure.

After his victory, Netanyahu said that he still supported Palestinian statehood, but saw it as impossible under current conditions.

Obama, already bothered by Netanyahu’s speech before Congress, said then that he would “reassess” Washington’s longstanding policy of defending Israel in international forums.

Those two issues, on top of the disagreements over Iran’s nuclear program, had seemingly imperiled the U.S.-Israel alliance.

But Dermer promised Israel would remain a strong partner—and a continued stable force in the Middle East, no matter the policy moves made outside its control.

“Israel is a very strong country with a very strong economy, and a very resilient public,” Dermer said. “We didn’t come back from 2,000 years of exile to see a bunch of fanatical ayatollahs cut the thread of Jewish history. That’s not gonna happen.”

“We have to stay very strong, and have to recognize that because Israel is a very strong country, we can go from great strength to great vulnerability like that,” he continued. “If Israel makes mistakes, we can become very vulnerable very quickly. We cannot roll the dice on the future of the one and only Jewish state.”