Oral arguments at the Supreme Court today were fascinating. Over two and a half hours of discussion about whether the Constitution requires all 50 states to treat same-sex relationships as marriages highlighted one essential truth: There are good policy arguments on both sides of the marriage debate and the Constitution doesn’t take sides in it.

Last year, the 6th Circuit Court ruled that the state marriage laws in Ohio, Tennessee, Michigan and Kentucky—all democratically defining marriage as the union of husband and wife—were good law. The 6th Circuit ruled that these state marriage laws did not violate the Constitution. Earlier today, lawyers on both sides of that question presented their best arguments to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court should conclude that the 6th Circuit got it right: The Constitution does not require the redefinition of marriage.

After all, the nine justices on the Supreme Court do not have a crystal ball. They cannot predict whether redefining marriage to include same-sex relationships will strengthen marriage or weaken marriage. They cannot predict whether it will be good for children or bad for children. They heard arguments on both sides of these questions—and the Constitution doesn’t tell them what the future will hold.

Indeed, the first few questions asked by the justices from the bench gives us a glimpse into how the Court is considering this issue.

Consider Justice Anthony Kennedy, who asked the third question:

One of the problems is when you think about these cases you think about words or cases, and—and the word that keeps coming back to me in this case is—is millennia, plus time.

First of all, there has not been really time, so the respondents say, for the federal system to engage in this debate … But still, 10 years is—I don’t even know how to count the decimals when we talk about millennia. This definition has been with us for millennia. And it—it’s very difficult for the Court to say, oh, well, we—we know better.

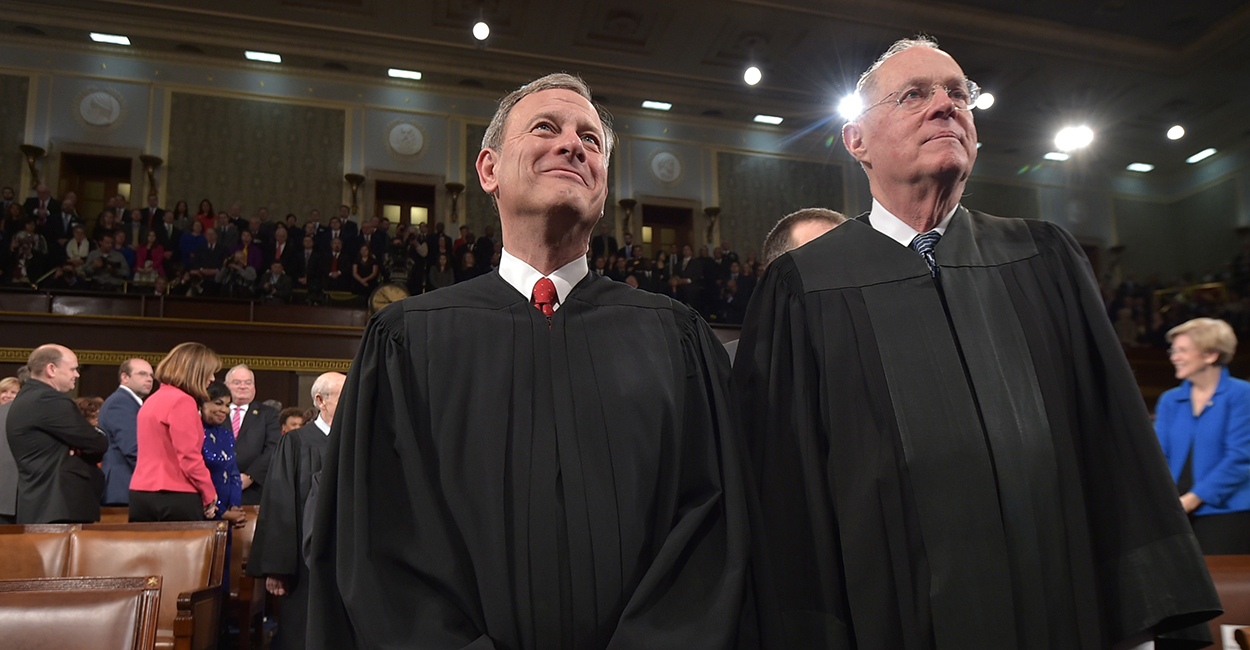

Chief Justice John G. Roberts and Supreme Court Justice Anthony M. Kennedy (Photo: Mandel Ngan/Pool/Newscom)

Chief Justice John Roberts asked the second question and suggested that while one side says they want to “join in the institution,” the other side says “they’re seeking to redefine the institution.” Roberts went on to add:

Every definition that I looked up, prior to about a dozen years ago, defined marriage as unity between a man and a woman as husband and wife. Obviously, if you succeed, that core definition will no longer be operable.

Roberts then concluded: “My question is you’re not seeking to join the institution, you’re seeking to change what the institution is. The fundamental core of the institution is the opposite-sex relationship and you want to introduce into it a same-sex relationship.”

This is why marriage policy needs to be made democratically. Redefining marriage to include same-sex relationships isn’t required by the Constitution, and it runs the risk of causing harm to the institution of marriage as a whole and to children in particular.

If the Court is to be consistent with its marriage ruling from just two years ago, then the Court must uphold state marriage laws defining marriage as the union of husband and wife.

The nine justices on the Supreme Court don’t have any more great insight than ordinary citizens do as to which marriage policy will serve the 50 states best. Unelected judges shouldn’t throw out the votes and voices of over 50 million citizens on this particular debate.

Even Justice Stephen Breyer got in on the act, noting that marriage understood as the union of a man and a woman “has been the law everywhere for thousands of years among people who were not discriminating even against gay people, and suddenly you want nine people outside the ballot box to require states that don’t want to do it to change … what marriage is to include gay people.”

He concluded: “Why cannot those states at least wait and see whether in fact doing so in the other states is or is not harmful to marriage?”

Justice Samuel Alito highlighted the same cross-cultural historical point:

How do you account for the fact that, as far as I’m aware, until the end of the 20th century, there never was a nation or a culture that recognized marriage between two people of the same sex? Now, can we infer from that that those nations and those cultures all thought that there was some rational, practical purpose for defining marriage in that way or is it your argument that they were all operating independently based solely on irrational stereotypes and prejudice?

Even Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who asked the first question, noted that the Supreme Court’s decision from just two years ago seems to suggest that states have the authority to make marriage policy: “What do you do with the Windsor case where the court stressed the federal government’s historic deference to states when it comes to matters of domestic relations?”

Indeed, the lawyers defending the state laws highlighted how the Supreme Court’s ruling just two years ago on the federal Defense of Marriage Act hinged on the fact that states have constitutional authority to make marriage policy.

If the Court is to be consistent with its marriage ruling from just two years ago, then the Court must uphold state marriage laws defining marriage as the union of husband and wife. Nothing in the Constitution requires all 50 states to redefine marriage.

Marriage exists to bring a man and a woman together as husband and wife, as well as to be father and mother to any children their union produces. Marriage is based on the anthropological truth that men and woman are distinct and complementary, the biological fact that reproduction depends on a man and a woman, and the social reality that children deserve a mother and a father.

Marriage is society’s best way to ensure the well-being of children. State recognition of marriage protects children by encouraging men and women to commit to each other—and to take responsibility for their children.

Redefining marriage to make it a genderless institution fundamentally changes marriage: It makes the relationship more about the desires of adults than about the needs—or rights—of children. It teaches the lie that mothers and fathers are interchangeable.

Rather than rush to a 50-state “solution” on marriage policy for the entire country, the Supreme Court should allow the laboratories of democracy the time and space to see how redefining marriage will impact society as a whole. There is no need for the Court to “settle” the marriage issue like it tried (unsuccessfully) to settle the abortion issue.

Because the Supreme Court cut the democratic process short on abortion, there is no issue less settled in American public life than abortion. Our politics on abortion are so polarized because the Court didn’t allow the democratic process to work. Why would the Court want to repeat that mistake? Why would the Court want to enflame the Culture War?

Allowing marriage policy to be worked out democratically will give citizens and their elected representatives the freedom to arrive at the best public policy for everyone.

At the end of the day, this is a debate about whether citizens or judges will decide an important and sensitive policy issue—in this case, the very nature of civil marriage. This is a debate about whether the Court will launch a new generation of cultural controversy. To avoid launching that controversy, the Court should do what the Constitution requires: Respect the authority of citizens to make marriage policy in the states.