As the U.S. Supreme Court hears oral arguments about gay marriage Tuesday, it’s important to realize what the justices are actually being asked to settle.

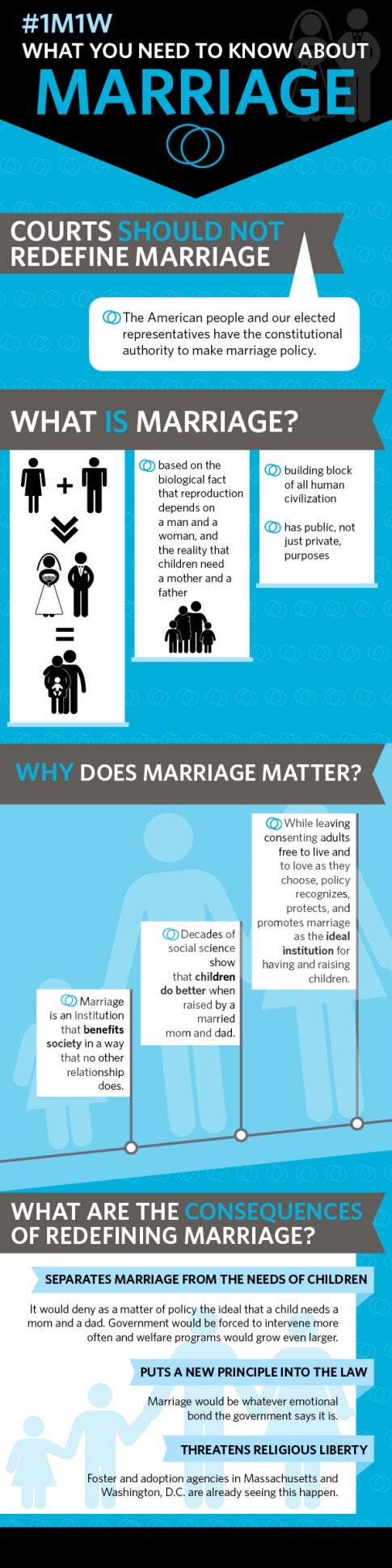

Here’s the bottom line: Whatever people may think about marriage as a policy matter, everyone should be able to recognize the U.S. Constitution does not settle this question. Unelected judges shouldn’t insert their own policy preferences about marriage and then say the Constitution requires them everywhere.

There simply is nothing in the Constitution that requires all 50 states to redefine marriage.

After all, the overarching question before the Supreme Court is not whether a male–female marriage policy is the best, but only whether it is allowed by the Constitution. Nor is it whether government-recognized same-sex marriage is good or bad policy, but only whether it is required by the Constitution.

Everyone in this debate favors marriage equality. Everyone wants the law to treat all marriages in the same ways. The only disagreement our nation faces is over what sort of consenting adult relationship is a marriage. Since the Constitution doesn’t answer that question, the people and their elected representatives should.

As Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito pointed out two years ago, there are two different visions of marriage on offer. One vision of marriage sees it as primarily about consenting adult romance and care-giving. Another vision sees it as a union of man and woman—husband and wife—so that children would have moms and dads.

There simply is nothing in the Constitution that requires all 50 states to redefine marriage.

Our Constitution is silent on which of these visions is correct, so We the People have constitutional authority to make marriage policy.

Those suing to overturn male-female marriage laws thus have to prove that the Constitution prohibits the man–woman marriage policy that has existed in the United States throughout our entire history … which they cannot successfully argue.

Nor is the debate over whether to redefine marriage to include same-sex relationships like the debate over interracial marriage. Race has absolutely nothing to do with marriage, and there were no reasonable arguments ever suggesting it did.

Laws that banned interracial marriage were unconstitutional, and the Court was right to strike them down. But laws that define marriage as the union of a man and woman are constitutional, and the Court shouldn’t strike them down.

Marriage exists to bring a man and a woman together as husband and wife, as well as to be father and mother to any children their union produces. Marriage is based on the anthropological truth that men and woman are distinct and complementary, the biological fact that reproduction depends on a man and a woman, and the social reality that children deserve a mother and a father.

Marriage is society’s best way to ensure the well-being of children. State recognition of marriage protects children by encouraging men and women to commit to each other—and to take responsibility for their children.

Redefining marriage to make it a genderless institution fundamentally changes marriage: It makes the relationship more about the desires of adults than about the needs—or rights—of children. It teaches the lie that mothers and fathers are interchangeable.

Rather than rush to a 50-state “solution” on marriage policy for the entire country, the Supreme Court should allow the laboratories of democracy the time and space to see how redefining marriage will impact society as a whole. There is no need for the Court to “settle” the marriage issue like it tried (unsuccessfully) to settle the abortion issue.

As I told George Stephanopoulos Sunday on ABC’s “This Week,” because the Supreme Court cut the democratic process short on abortion, there is no issue less settled in American public life than abortion.

Our politics on abortion are so polarized because the Court didn’t allow the democratic process to work. Why would the Court want to repeat that mistake? Why would the Court want to enflame the Culture War?

Allowing marriage policy to be worked out democratically will give citizens and their elected representatives the freedom to arrive at the best public policy for everyone.

As the 6th Circuit noted when it upheld several states’ marriage laws, “federalism … permits laboratories of experimentation—accent on the plural—allowing one State to innovate one way, another State another, and a third State to assess the trial and error over time.” Judges should not cut this process short.

At the end of the day, this is a debate about whether citizens or judges will decide an important and sensitive policy issue—in this case, the very nature of civil marriage. This is a debate about whether the Court will exacerbate the Culture War again. Peace and harmony suggest democracy is the better path. The Constitution requires it, too.

Originally distributed through the Tribune Content Agency.