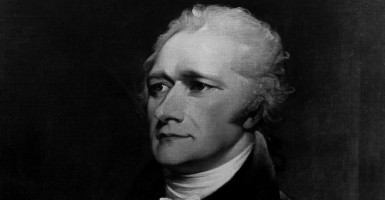

Some conservatives are tempted to dismiss or regret the statesmanship and political thought of Alexander Hamilton, our nation’s first Secretary of the Treasury. This temptation may arise as a reaction to the efforts of some progressives to invoke Hamiltonianism as a founding-era precedent for their own desire for an activist and expansive federal government. Uncritically accepting such progressive arguments, some conservatives view Hamilton as an early American proponent of big government.

Conservatives who are tempted to think this way should take a closer look at Hamilton’s career.

As I argue at greater length in a new essay entitled “Alexander Hamilton and American Progressivism,” he was not a proto-progressive. Nor was he the progenitor, wittingly or unwittingly, of the kind of expansive central state that modern liberals support in their quest to achieve social justice.

To be sure, in his own day Hamilton was known not so much as a proponent of limited government as a proponent of energetic government. And Hamilton argued for a broad interpretation of the national government’s powers precisely with a view to enabling the energetic government he thought necessary to the infant republic’s security and flourishing.

Hamilton favored an active federal government, but he did so on grounds and within limits that are recognizably within the American conservative and constitutional tradition.

Hamilton argued for a broad reading of the Necessary and Proper Clause in order to justify the constitutionality of the first national bank, which he thought a crucial support for the government’s ability to borrow money. He argued for a broad reading of the General Welfare Clause in order to justify the constitutionality of bounties (or subsidies) paid to manufacturers, which he thought essential to building an American manufacturing sector.

Nevertheless, Hamilton advocated such policies not as a progressive, but instead as a pragmatic conservative statesman, seeking to build a government and economy that would make America an independent, prosperous, and powerful nation.

Hamilton’s Conservatism

Hamilton’s conservatism is evident, in the first place, in the way he argued for institutions like the national bank and bounties for America’s infant manufacturing sector.

Unlike a contemporary progressive, he did not favor these things because they were new or innovative. On the contrary, he advocated them precisely on the conservative ground that they had been tried, and their usefulness proven, in other countries.

Successful commercial and manufacturing nations, he observed, had national banks and had taken some steps to encourage the development of their nascent domestic manufactures.

Hamilton’s conservatism is also evident in the ends he had in view in advocating such policies.

House conservatives want to use a process known as budget reconciliation to repeal the Affordable Care Act. (Photo: Pete Marovich/ZUMAPRESS/Newscom)

The primary driver of contemporary liberalism’s demand for expansive government authority is contemporary liberalism’s egalitarianism. This can be seen in the debate over the Affordable Care Act. Even though America in 2009 could boast a health care system among the best in the history of the entire world, it was not good enough for American liberals.

And why not? Because of inequality. Most Americans had adequate health insurance, but some didn’t.

This is not the kind of thinking that informed Alexander Hamilton’s statesmanship. Indeed, Hamilton was accused by his political enemies of being an aristocrat. Those charges were unjust, but they certainly could not have been made if he had dedicated his public efforts, like a contemporary liberal, to the pursuit of an ever greater equality of conditions.

The end Hamilton had in mind in advocating his policies was instead the prosperity, power and prestige of the nation—within which enterprising individuals and families could work effectively to better their condition.

A Government Can Be Both Limited and Energetic

Nor should contemporary conservatives reject Hamilton because of his call for an energetic national government. This call was consistent with the purposes of the American founding and not a betrayal of them. The Constitution was written and ratified, after all, because the government of the United States was too weak, unable to pay its bills and defend the country.

The aim of the Constitution, then, is to create a government that is both energetic but also limited. And Hamilton’s career reminds us that this is what we should want: a government that energetically executes its proper functions but does not go beyond them.

It is true that Hamilton was accused by Jefferson and Madison of pushing the powers of the national government beyond their proper limits. His response to such charges, however, showed a proper respect for the Constitution that is often lacking among contemporary progressives.

Hamilton replied to to these accusations by arguing that his policies were in fact justified by a correct interpretation of the Constitution. He certainly did not respond by suggesting, as contemporary liberals sometimes do, that the Constitution could be ignored because it is supposedly inadequate to the needs of a dynamic and changing nation.

In sum, the debate between Hamilton and his opponents was a debate over how to understand the limits on government imposed by the Constitution, not a debate about whether those limits should be respected.

Hamilton and the Other Founders

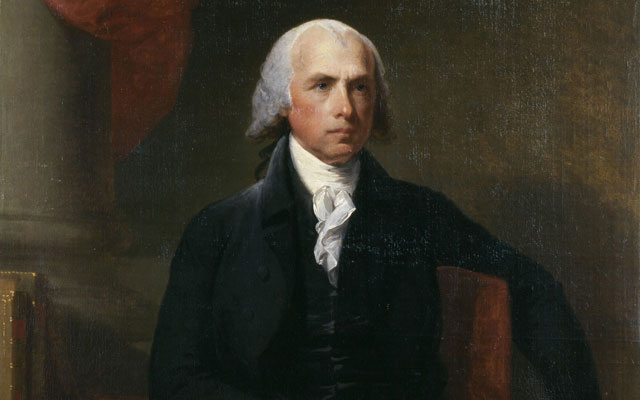

Similarly, Hamilton stood with the rest of the founding generation in supporting separation of powers and federalism as principles that limited and moderated the exercise of the national power. He agreed with James Madison that separation of powers was essential to preventing the tyrannical exercise of government power.

And while he sought to shore up the national power because he thought this was what the infant republic needed to achieve stability, he admitted that the states were an essential part of America’s constitutional scheme and that they would serve as a salutary check on the power of the federal government.

The state legislatures, Hamilton argued in “Federalist” 26, would act as “not only vigilant but suspicious and jealous guardians of the rights of the citizens against encroachments from the federal government.”

Above all, Hamilton accepted and unswervingly defended the natural rights doctrine that informed the founding, a doctrine that contemporary conservatives care called upon to defend as well.

For Hamilton, as much as for Jefferson and Madison, governments were instituted to protect the rights of individuals, including their right to acquire property, even unequal amounts of property.

As the statesman charged with finding a way for America to pay its war debts, Hamilton made the right of private property one of the guiding principles of his plan to restore the public credit. He never suggested that the government could escape its debts by repudiating them, thus violating the property rights of the debt holders.

On the contrary, he insisted that “the established rules of morality and justice are applicable to nations as well as to individuals,” and “that the former as well as the latter are bound to keep their promises, to fulfill their engagements,” and “to respect the rights of property.”

Contemporary conservatives are certainly not obligated to adopt Hamilton as their favorite founder, or to derive their policies for today from his thinking about the challenges of his own time.

On the other hand, neither should they deprive themselves of the benefits of studying his statesmanship by accepting the erroneous view that he was a proto-progressive or an early advocate of big government. Hamilton favored an active federal government, but he did so on grounds and within limits that are recognizably within the American conservative and constitutional tradition.