Gov. Mike Pence gained national attention when he signed the Indiana Religious Freedom Restoration Act into law last week.

It caused the Twitter hashtag #BoycottIndiana to go viral and triggered Apple CEO Tim Cook to pen a Washington Post op-ed calling “pro-discrimination” laws “dangerous.”

Yet, despite the uproar, Indiana isn’t alone in enacting legislation that seeks to protect the religious freedom of its citizens.

Religious Freedom Restoration Acts—or what critics call “pro-discrimination” laws—have been around for over two decades.

Religious Freedom Restoration Acts first came about after the Supreme Court’s 1990 decision in Employment Division v. Smith, which “narrowed protections for the free exercise of religion.”

In response to the court’s ruling, Congress sought to restore religious freedom by passing the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, popularly known as RFRA.

The legislation won unanimous support in the House, passed 97-3 in the Senate, and was signed into law by then-President Bill Clinton.

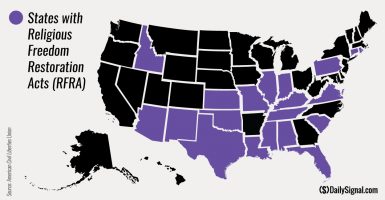

Since then, in addition to Indiana, 19 states have passed their own state-level Religious Freedom Restoration Acts: Alabama, Arizona, Connecticut, Florida, Idaho, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia.

Another 11 states have RFRA-like protections provided by state court decisions.

Under Indiana’s new law, “[T]he state cannot substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion unless it is furthering a compelling government interest and acting in the least restrictive way possible.”

Critics say the legislation will enable business owners to discriminate against people based on their sexual orientation—or as Hillary Clinton put it, because of “who they love.”

Sad this new Indiana law can happen in America today. We shouldn't discriminate against ppl bc of who they love #LGBT http://t.co/mDhpS18oEH

— Hillary Clinton (@HillaryClinton) March 27, 2015

They also argue Indiana’s religious freedom law, which goes into effect in July, is more loosely written than other RFRAs. Pence has said that he plans to “clarify” the law’s intent.

But those who support RFRAs—including The Heritage Foundation’s Ryan Anderson, who researches and writes about marriage and religious liberty—argue RFRAs are not written to be “anti-gay.”

Anderson says Indiana’s RFRA does not allow business owners to refuse service based on a person’s sexual orientation.

He argues that the law provides those with strong religious beliefs a shield from being discriminated against for dissenting against popular opinions about marriage or other faith-based matters.

“This debate has nothing to do with refusing to serve gays simply because they’re gay, and this law wouldn’t protect that,” he told The Daily Signal.

The religious liberty concern centers on the reasonable belief that marriage is the union of a man and a woman. The question is whether the government should discriminate against these citizens, should the government coerce them into helping to celebrate a same-sex wedding and penalize them if they try to lead their lives in accordance with their faith? A Religious Freedom Restoration Act could protect these citizens. But it might not.

>>> Commentary: Apple CEO Is Wrong About Indiana Religious Freedom Law

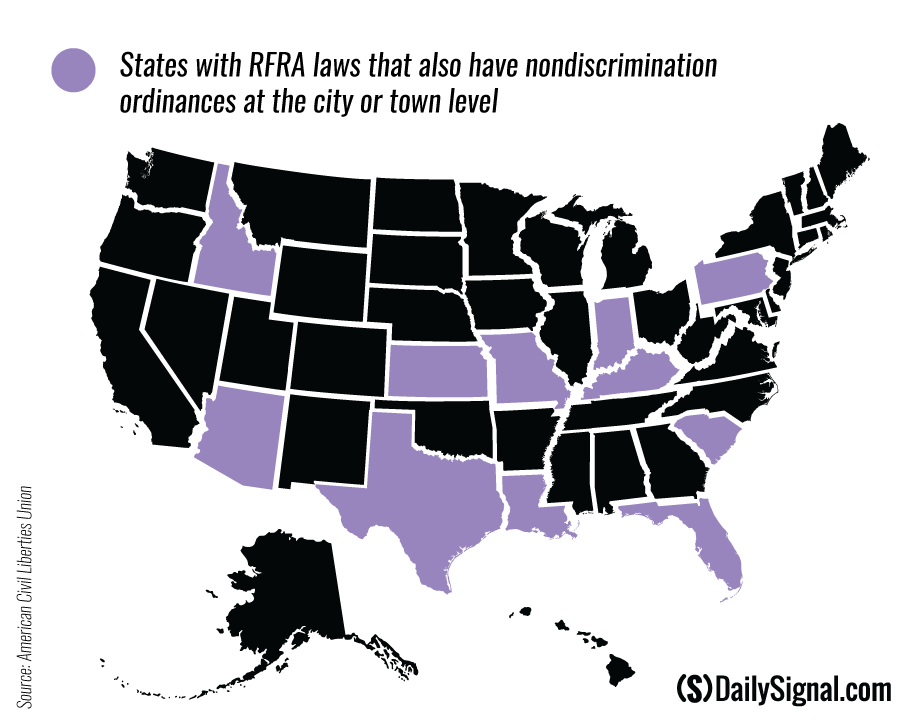

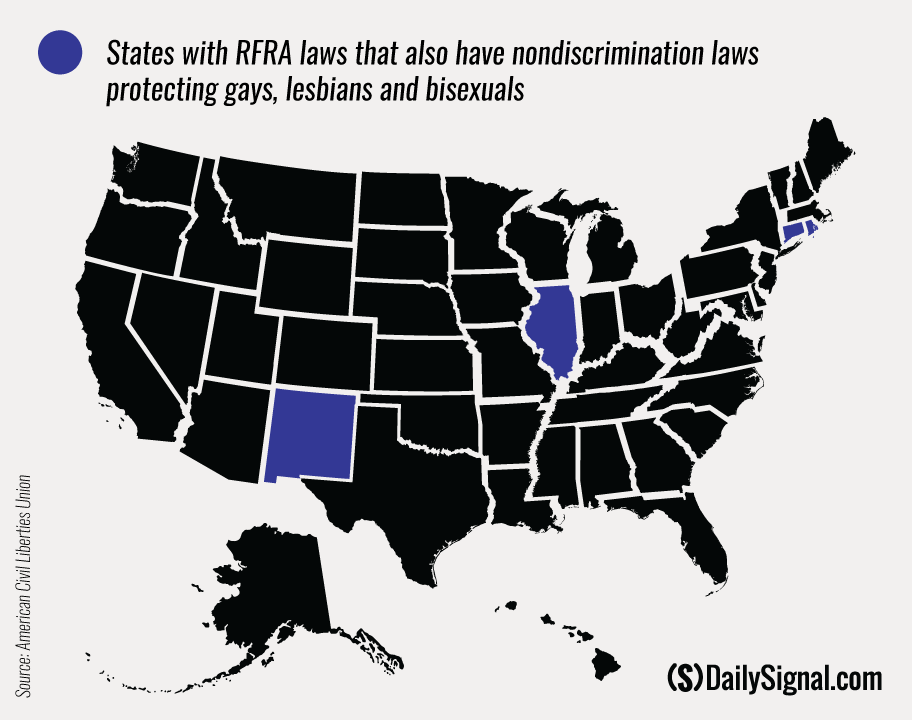

But Indiana is different than some other states that have RFRAs in at least one way.

Unlike Connecticut, Illinois, New Mexico, and Rhode Island, which in addition to RFRAs, also passed some form of legislation explicitly banning the discrimination against people based on their sexual orientation, Indiana doesn’t have a law on the books that specifically protects against the discrimination of gays and lesbians.

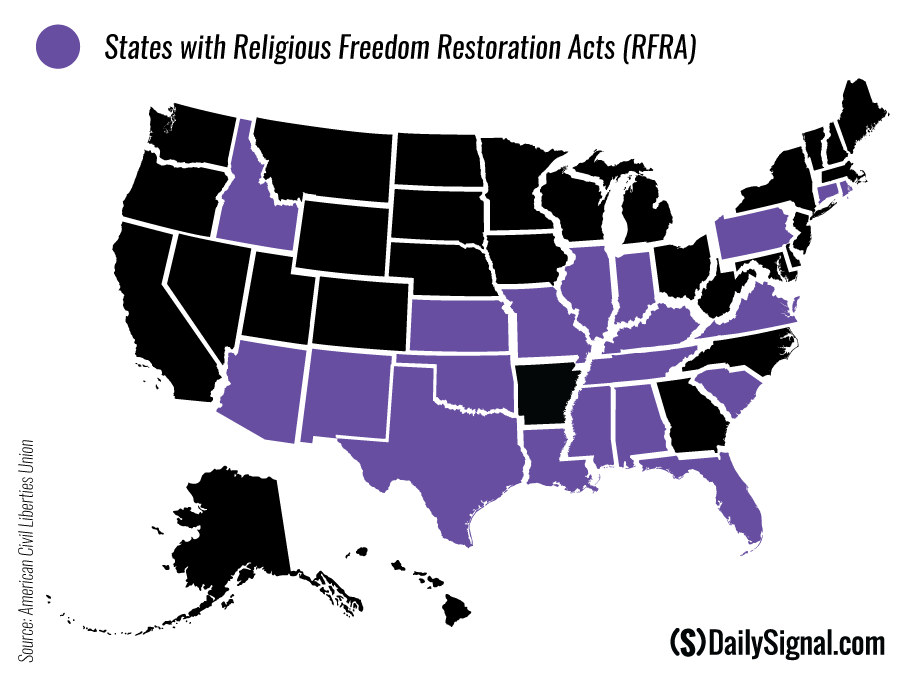

Critics of Indiana’s new law say because there is no state law protecting gays and lesbians (only measures in certain cities throughout the state), those people may be discriminated against through the RFRA.

They also fear supporters of the RFRA will use it to undermine the few local nondiscrimination laws that do exist in cities like Indianapolis.

Those in favor of RFRA laws argue nondiscrimination legislation shouldn’t matter much in the eyes of the court because there have been no cases to date where business owners refused service simply based on a person’s sexual orientation.

There have been instances where business owners refused service to gay and lesbian customers—like when a 70-year-old florist from Washington would not design floral arrangements for a same-sex marriage.

But in those situations, the business owners who denied service said they should not be forced to contribute to a religious ceremony that conflicts with their religious beliefs.

“I did serve Rob,” Barronelle Stutzman, the Washington florist, told The Daily Signal in an earlier interview. “It’s the event that I turned down, not the service for Rob or his partner.”

Still, Washington state—which doesn’t have a RFRA—ruled against Stutzman, finding her in violation of the state’s anti-discrimination and consumer protection laws.

>>> Read More: State Says 70-Year-Old Flower Shop Owner Discriminated Against Gay Couple. Here’s How She Responded.

Cases such as Stutzman’s are why many religious freedom advocates argue that it’s important that states adopt RFRAs as protections.

“The law doesn’t say who will win,” Anderson said. “Only that a court should review, using a well-established balancing test, and hold the government accountable to justify its action.”

Some of the attached graphics have been corrected.