In a letter to Iran this week, nearly four dozen Republican senators showcased the limitations of a potential unilateral nuclear deal by President Obama, rightly warning that the future U.S. president could reverse the agreement.

But in trying to assert their power, the senators skirted over the fact that presidents have executive authority to make deals with foreign countries—without needing to go to Congress.

While Republican congressional leaders are pushing the Obama administration to handle its nuclear negotiations with Iran as a treaty, which would require approval from two-thirds of the upper chamber, history shows that presidents can—and often do—avoid this requirement by forging “executive agreements” with foreign countries.

Executive agreements are international agreements that do not require congressional approval in some instances. However, the compacts can be reversed by both the current and succeeding presidents.

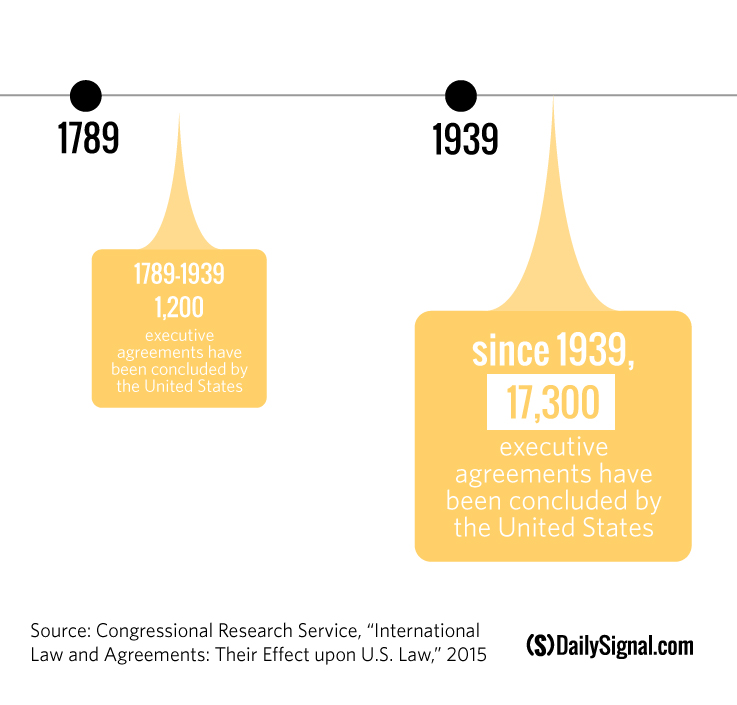

Executive agreements have been used for more than two centuries. According to a February report from the Congressional Research Service, the U.S. has concluded more than 18,500 executive agreements since 1789.

However, the majority of those covenants—17,300—occurred after World War II, when presidents’ use of executive agreements increased substantially.

The Congressional Research Services notes, however, that the number of executive agreements likely tops 18,500, as “minor or trivial undertakings” aren’t included in the total.

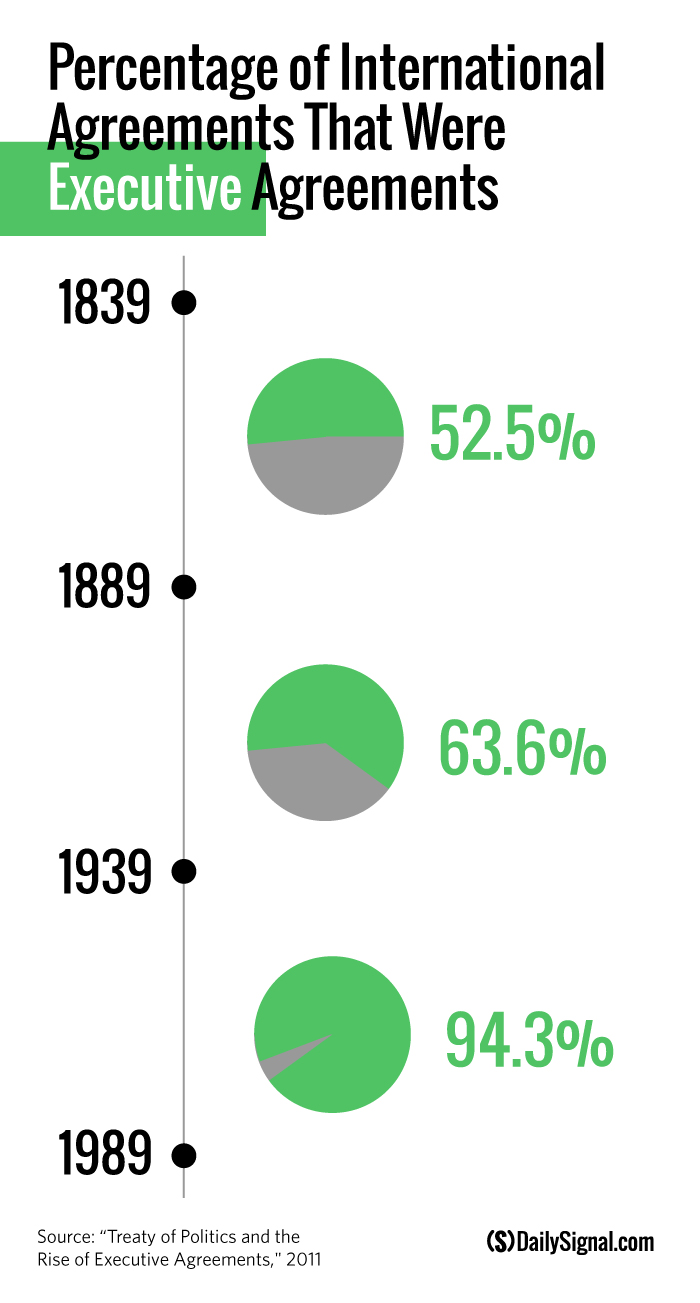

According to the book “Treaty Politics and the Rise of Executive Agreements,” executive agreements have made up a substantial portion of all international agreements of modern history.

From 1889 to 1939, 63.6 percent of international agreements were executive agreements.

From 1939 to 1989, however, that percentage grew to 94.3.

In an interview with The Daily Signal, Jeffrey Peake, a professor at Clemson University and one of the book’s authors, said the increase in executive agreements can be attributed to a shift in foreign policy over centuries.

“Foreign policy is so much more complex today than it was ever envisioned by our framers,” he said. “To go back in the Constitution and say everything should be done as a treaty is naive.”

However, Arthur Milikh, an expert in America’s founding principles at The Heritage Foundation, told The Daily Signal not signing a treaty with Iran could put the president in a precarious situation in the future.

“Regardless of the new complexities introduced into foreign policy by technology and international organizations, the fact remains that we are a republic, which is to say a people ruled by consent,” he said. “The Senate is given treaty powers as an expression of popular consent on issues that could lead to war. In this case, the president may be in a bind if or when Iran violates an agreement not approved by the Senate.”

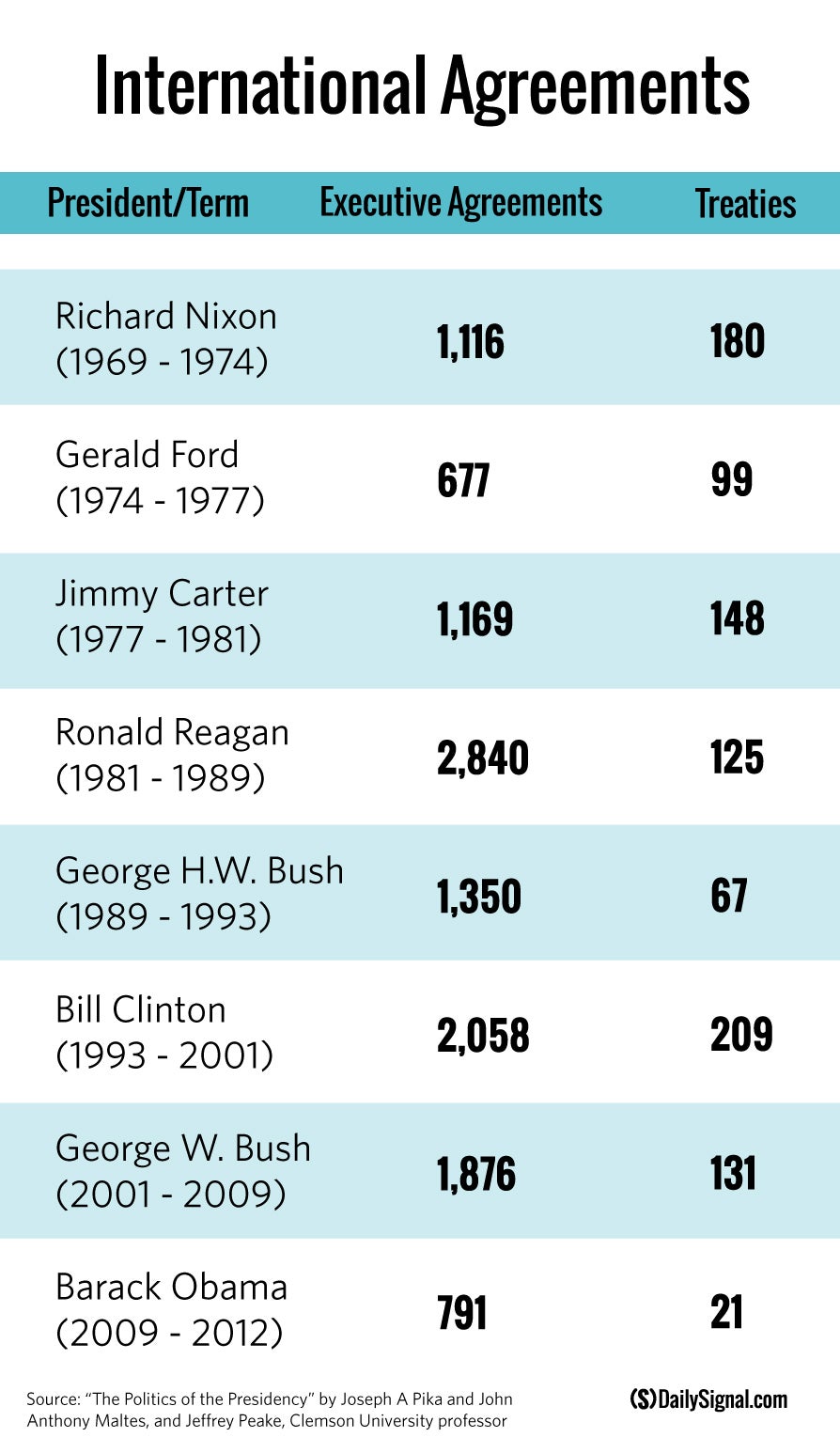

All of the modern presidents have exercised their ability to use executive agreements, with Presidents Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton using the international agreement more liberally.

However, each president’s executive agreements far outweigh their use of treaties.

Peake noted that Obama has sent far fewer treaties to Congress than his predecessors, likely because of the legislative branch’s divisive nature.

“I think that this is just the continuation of a trend of the politicization of the international agreement process,” he said. “Domestic policies have become more partisan, and the parties are so polarized that there’s really been a breakdown of the standard process.”

Historically, presidents typically have notified Congress before entering into executive agreements, using them with the legislative branch’s tacit approval. In 2002, for example, President George W. Bush was contemplating nuclear arms reduction with Russia. Bush originally wanted to bill the deal as an executive agreement, but was met with resistance from then-Sens. Joe Biden, D-Del., and Jesse Helms, R-N.C.

>>> Here’s What GOP Presidential Hopefuls Think About Tom Cotton’s Letter to Iran

The 43rd president submitted the agreement as a treaty, requiring Senate approval.

“The president is always safest when he acts with the tacit approval or at least the joint action of Congress,” Peaks said. “In this case, it doesn’t seem like [Obama] can given the opposition to the agreement. So, what the White House has been doing—the president is trying to figure out other ways it can be done. This brings us into the domain on the use of unilateral action by the executive.”

Peake said the legislative branch would eventually play a role in negotiations with Iran, as congressional approval is needed to fully roll back sanctions—a bargaining chip the White House is using to tempt Iran into a deal.

“The executive branch could be pushing the envelope a little bit on what constitutes an executive agreement as opposed to a treaty where Congress might come into play,” he said. “They’re saying this is a ‘non-binding agreement’ so Congress doesn’t have anything to say about it, except when it comes to implementing it when we deal with sanctions. So at that point, Congress would have some say.”

“The executive branch could be pushing the envelope a little bit on what constitutes an executive agreement as opposed to a treaty where Congress might come into play,” said Jeffrey Peake.

Reuters reported Thursday that in an effort to make it harder for Republicans and future presidents to undo the nuclear agreement, major world powers are in talks about a United Nations Security Council resolution to lift U.N. sanctions on Iran.

>>> Is Obama Sidestepping Congress and Going to the UN on the Iran Deal?

The report says that the talks between Britain, China, France, Russia and the United States, plus Germany and Iran, could be legally binding, complicating any effort to reverse a nuclear agreement.