Arthur Milikh, assistant director of the B. Kenneth Simon Center for Principles and Politics at The Heritage Foundation, explained in a column earlier this week why Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., was right when he said both the Senate and the president should sign on to treaties:

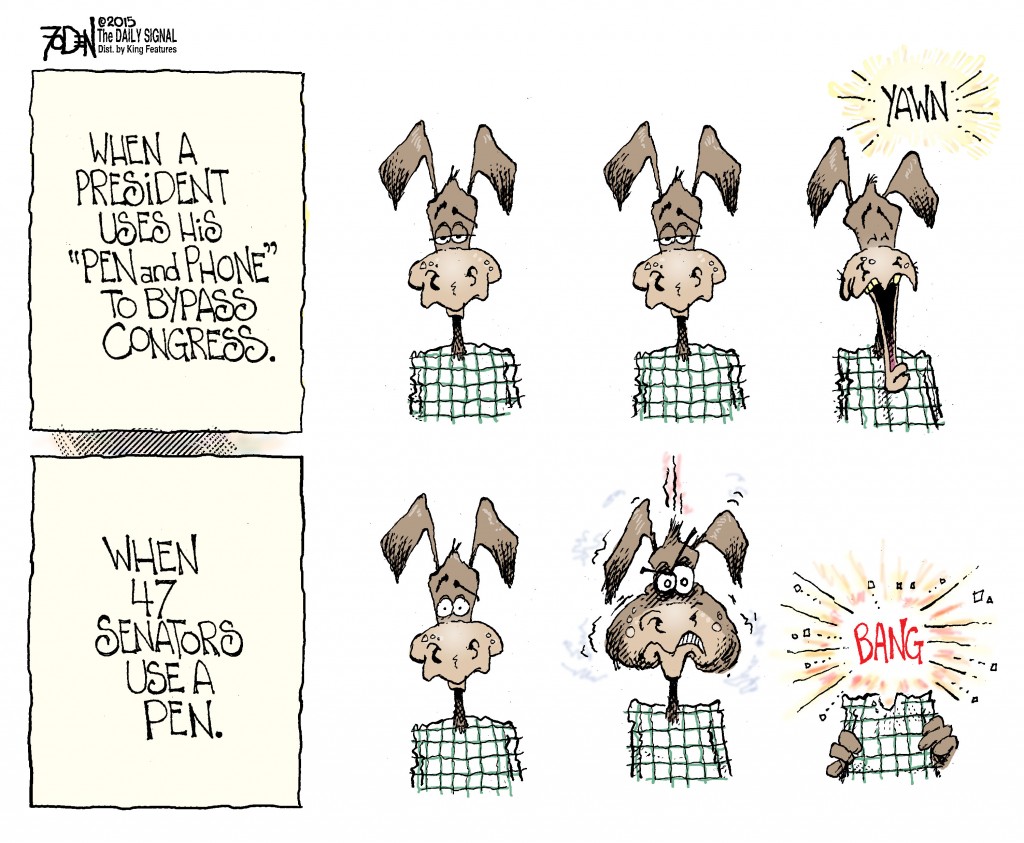

In a letter written by Sen. Tom Cotton and 46 other senators to Iran’s leadership—but also, of course, intended for President Obama—the signatories state that without Senate ratification, a deal between the United States and Iran is unlikely to outlast the current president.

This letter perfectly showcases the intelligence beneath our constitutional design. For America’s founders, both the Senate and the presidency are to channel and accentuate the best qualities of each institution, while preventing either from acting alone, especially in foreign policy.

Each institution has its own distinct character and limitation—and each compliments the other. A president, for example, although constrained by law, is allowed secrecy, and much room for movement, which are necessary for commanding and governing. The presidency thus requires “energy,” as the Federalist Papers state.

But most importantly, the presidency is intended for the most ambitious men in our country. And this is a good thing.

That is because the public can be the beneficiary of a president’s ambitions: presidents want to be thought well of—to make a legacy, as we call it—and in order to do this they must serve the public good. As Hamilton observes in Federalist 72 “the love of fame…would prompt a man to plan and undertake extensive and arduous enterprises for the public benefit.”

Yet there are problems with too much energy and ambition—and they must be constrained. In our present situation, for example, we have an ambitious president who, overcome by his desire for fame, has gone in the direction of exaggerating his powers by attempting to singlehandedly solve the conflict with Iran.

Of course resolving such conflicts requires the energy of a single person, since commanding, going to war, and deciding must be done alone, rather through a committee or a congressional body. But the Federalist understood that energy and ambition do not always have prudence. And prudence, for the Federalist, was to be the reserve of the Senate, a body designed to have “sufficient permanency to provide for such objects as require a continued attention.” This is why treaties require both a president and the Senate: part energy, part prudence.

The Senate is designed to be far-seeing. Senators are supposed to be more than merely politicians, but a class unto themselves, with vision into that unknown continent of the future. That is why they were not originally intended to be elected by popular vote. Their six-year terms are meant to insulate them from the daily, noisy, consuming grind of politics so that they can think through the long, complicated objectives of foreign affairs—which require patient and careful navigation through many unknown obstacles.

Lastly, unlike the House, the Senate is not all at once up for reelection, but their cycles are staggered. This was designed so that one single passion, spreading through the public suddenly and all at once, could not remove the body meant to have a calm and thoughtful temperament: the kind of temperament possessing “discretion and discernment,” rather than energy and ambition.

The president and the Senate are two sides of the same coin. The senate should have the “talents, information, integrity,” while the president has “secrecy and dispatch.”

Cotton correctly points out that “President Obama will leave office in January 2017, while most of us will remain in office well beyond then—perhaps for decades.” The president would do well to remember that despite the seeming grandeur of his position he is only one part—the part that requires energy and ambition—and not the institution designed for long-term, deliberate thinking.