For the majority of states that adopted the Common Core national standards in 2010, this is the school year in which testing begins. And the haste with which Common Core was adopted and implemented has caused problems, adding to a host of concerns already surrounding Common Core.

In an article last month in Education Week magazine, reporter Liana Heitin reported that some Common Core expert reviewers felt rushed in their review of the standards. Heitin interviewed Hung-Shi Wu, professor emeritus of mathematics at the University of California, Berkeley, and a member of the Common Core development team. Wu concluded: “The amount of time given to the high school standards was definitely inadequate.”

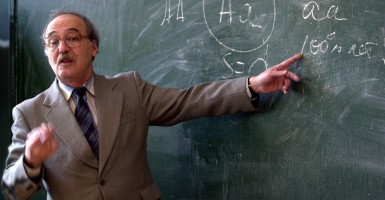

This is consistent with Dr. James Milgram’s ongoing critique of the standards since their development in 2009. Milgram, who serves as professor emeritus of mathematics at Stanford University, was one of five members of the 30-person Common Core validation committee who refused to sign on to the standards.

A Pioneer Institute report coauthored by Milgram detailed that, by seventh grade, Common Core mathematics standards leave American students two grade levels behind their peers internationally and do not prepare them for admission into highly selective four-year universities and STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) programs.

“If you came to college with only an Algebra II background and you wanted to major in a STEM area, you have a 1/50 chance— a 2 percent chance— of ever obtaining a degree in STEM… This level of preparation is simply insufficient,” said Milgram.

According to Education Week, teachers also are struggling with how to teach to the Common Core math standards.

“Each standard has so many ideas built into it, you really have to sit down and think through all the implications of that,” said math teacher Bobson Wong. “I could easily make each of these courses a two-year course.”

And recently, reports surfaced that the Common Core architects left what some consider holes in the standards.

Richard A. Askey, a professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and former member of the math standards’ feedback group, later noticed an omission of a geometry standard in Common Core. In fact, according to Education Week, Askey said “the process toward the end was so hurried that an entire high school standard was left out of the final draft.”

“There’s no formal mechanism in place for a wholesale review of the common core, but it’s likely that states will—as they always have—review their standards at times and decide whether they need to be altered,” the Education Week article said.

When Common Core was created in 2009 by Achieve Inc., with oversight from the National Governors Association and the Council of Chief State School Officers, its adoption immediately was tied to federal incentives through billions in competitive grants and waivers from provisions in the No Child Left Behind law.

By 2010, 46 states had signed on to the standards and agreed to implement them fully by this school year. Over the last two years, states have begun to realize the costs of quickly signing on to Common Core. By 2015, 15 of the original 46 states that agreed to Common Core have made efforts to withdraw from the standards and aligned tests. Four exited the standards completely—Indiana, Oklahoma, South Carolina and Louisiana.

The haste of Common Core’s adoption is felt across the nation—but the extent is not yet realized. The alignment of college entrance exams, such as the SAT and ACT, and advanced placement courses cause concern over the “voluntary” nature of the standards.

Yet, there is still hope. Many states are putting forth measures to reclaim autonomy over their standards and are beginning to practice competitive federalism, thoughtfully considering their state standards, Common Core and other state standards to make a set of standards and tests that are best for their students’ college or career readiness.