High-level federal executives routinely use personal email for business, in likely violation of the Federal Records Act. That’s according to a recent survey of federal employees.

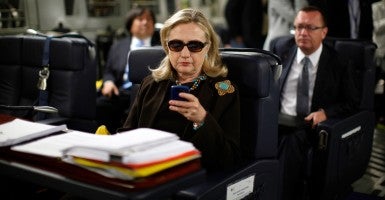

The survey was conducted by the research group Government Business Council just prior to revelations that Hillary Clinton allegedly exclusively used personal email and a private server at her Chappaqua, N.Y., residence for her government communications while serving as President Obama’s secretary of state.

Personal email is “always” or “often” used for government business in their agency, according to 16 percent of survey respondents. One-third, 33 percent, said personal email is used “sometimes” or more frequently.

Thirty-one percent said personal emails used for business are not preserved for archiving. Forty-seven percent said they don’t know whether or not the records are properly preserved.

Clinton: Not the First

The revelation about Clinton’s use of personal email is the latest, but not the first.

In fact, Clinton herself was a vociferous critic of the George W. Bush administration’s email practices after it was learned in 2007 that millions of White House emails sent on a non-government server may have been “lost.”

More recently, the State Department inspector general (IG) identified multiple instances of officials improperly using and failing to archive personal email from 2010 to 2014.

>>> 19 Times the Government Withheld Documents It Didn’t Want You to See

For example, the IG said officials at the U.S. Embassy in Bangkok, Thailand were not implementing procedures on records management and “email messages … are not preserved.”

IRS manager Lois Lerner allegedly used an msn.com email account labeled ‘Lois Home’ for government-related communications. Lerner was a key player in what the IG found was the tax agency’s unfair targeting of conservative groups.

Former Obama EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson used private email accounts, as well as a secret EPA email address under the pseudonym “Richard Windsor,” to conduct official business. That included communicating with a climate lobbyist.

“P.S. Can you use my home email rather than this one when you need to contact me directly? Tx, Lisa.” —EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson email to a lobbyist.

Jackson’s use of personal email accounts was inadvertently revealed in a Freedom of Information Act production. In an email chain between Jackson and a Sierra Club official, Jackson’s personal Verizon email address was redacted citing a “privacy exemption.” But it was left unredacted later in the thread.

The EPA inspector general recently found the agency’s Chemical Safety Board Chairman Rafael Moure-Eraso and two top officials used personal email accounts to conduct official business. The IG said the officials did not preserve the emails, in violation of federal regulations.

>>> Lawsuit Seeks EPA Administrator’s Deleted Messages

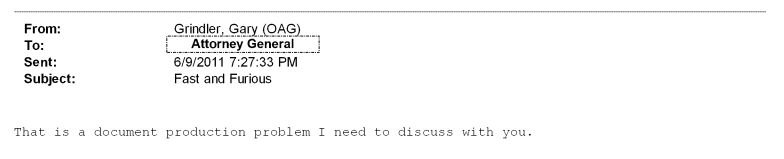

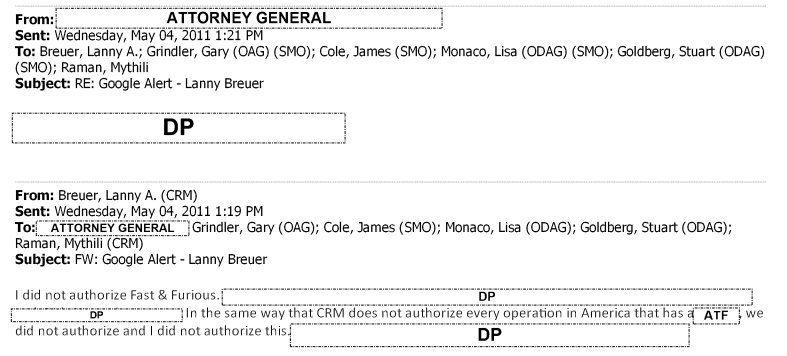

Attorney General Eric Holder’s criminal division head, Lanny Breuer, was caught forwarding controversial Fast and Furious-related emails to his personal account.

Obama Labor Secretary Thomas Perez, Holder’s former assistant attorney general for civil rights, allegedly used his private email account to leak non-public information about official business.

As to whether Holder himself ever used personal email for government business, the Justice Department isn’t saying. A spokesman did not respond to requests for information about Holder’s email practices.

In Justice Department emails turned over in a federal Freedom of Information Act lawsuit, Holder’s email name is redacted with no explanation. It’s unknown whether the redactions conceal use of an email address that does not belong to an official government account.

Fast and Furious-related emails between Holder and his wife Sharon Malone, and his mother, are currently being withheld under executive privilege invoked by President Obama.

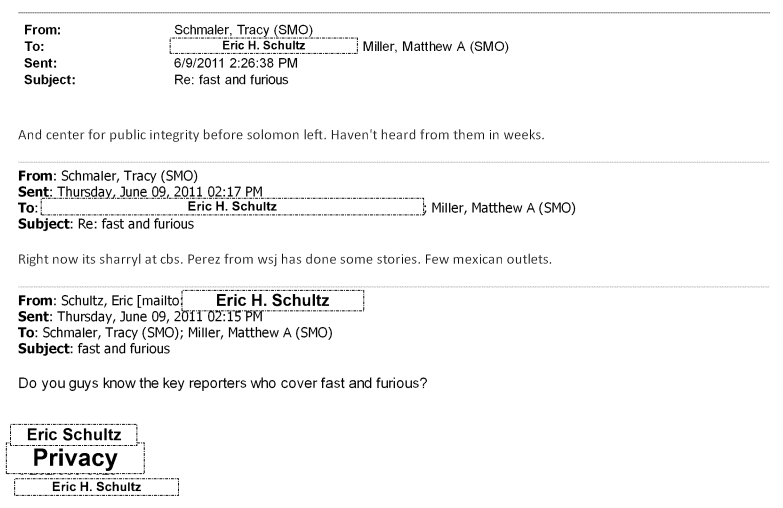

There are similar redactions of the email name for Obama adviser Eric Schultz. In one instance, “privacy” is cited as the reason. In other cases, no explanation is given.

Security Questions

Experts say it’s not only a question of whether federal officials are trying to skirt Freedom of Information law that requires release of public documents upon request; there are also security concerns. From that standpoint, Clinton’s example may be the most concerning.

Government Executive says security experts are “still scratching their heads about why Clinton would have taken the unusual step of setting up a home-managed email account, a move that potentially made her messages vulnerable to foreign hackers keen on spying on the U.S.’s top diplomat.”

“Computer-security analysts … warned that emails sent across separate servers—instead of delivered entirely within government servers—posed greater risk of being intercepted or spied on.” —@GovExec

A high-ranking government official familiar with the potential security risks says Clinton’s case raises many security issues.

“There are times when the location of the secretary of state and other cabinet members is sensitive” or even classified, said the official, “especially, if they are traveling with [the president].”

A smartphone using a commercial Internet service provider would theoretically broadcast its location most of the time, over an unauthorized network, including when that location classified, the official said.

The official also noted that it’s not known whether Clinton carried her phone into areas where classified discussions took place. “If she did, that [could be] a security violation.”

>>> Commentary: How to Free the Government’s Grip on Freedom of Information

The State Department has said Clinton did not send classified information via email. A Clinton spokesman has said she has been complying with the “letter and spirit of the [federal records] rules.”

Clinton sent a tweet last week shortly after the House Benghazi Committee subpoenaed her emails.

I want the public to see my email. I asked State to release them. They said they will review them for release as soon as possible.

— Hillary Clinton (@HillaryClinton) March 5, 2015

“There’s no doubt that there will not be a way to fully validate the completeness of that production,” Jason Straight told Government Executive. Straight is chief privacy officer and senior vice president of cybersecurity at UnitedLex.

2 Replies to “High-Ranking Federal Officials’ History of Using Personal Email for Government Business”